Utilisateur:SenseiAC/Grand Reich germanique

Le Grand Reich germanique (en allemand : Großgermanisches Reich), de son nom complet Grand Reich germanique de la Nation allemande (en allemand : Großgermanisches Reich Deutscher Nation) est le nom d'État officiel de l'entité politique que l'Allemagne nazie essaya d'établir en Europe pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale[2]. Albert Speer déclara dans ses mémoires qu'Adolf Hitler faisait aussi référence à l'État envisagé (![]() traduction, en anglais « envisioned state ») en tant que Reich teutonique de la Nation allemande, bien qu'il ne soit pas clair si Speer a utilisé le mot maintenant rarement employé de « teutonique » comme synonyme de « germanique »[3]. Hitler mentione également un futur État germanique de la Nation allemande (allemand : Germanische Staat Deutscher Nation) dans Mein Kampf[4].

traduction, en anglais « envisioned state ») en tant que Reich teutonique de la Nation allemande, bien qu'il ne soit pas clair si Speer a utilisé le mot maintenant rarement employé de « teutonique » comme synonyme de « germanique »[3]. Hitler mentione également un futur État germanique de la Nation allemande (allemand : Germanische Staat Deutscher Nation) dans Mein Kampf[4].

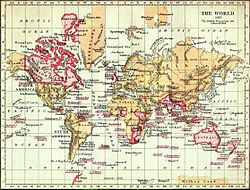

Il était prévu que cet empire pangermanique assimilât pratiquement toute l'Europe germanique dans un Reich énormément étendu. Territorialement parlant, il comprenait le Reich allemand déjà élargi lui-même (constitué de l'Allemagne propre d'avant 1938, de l'Autriche, de la Bohême, de la Moravie, de l'Alsace-Lorraine, d'Eupen-Malmedy, de Memel, de la Basse-Styrie, de la Haute-Carniole, de la Carinthie du Sud et de la Pologne occupée), les Pays-Bas, la partie flamande de la Belgique, le Luxembourg, le Danemark, la Norvège, la Suède, l'Islande, au moins les parties germanophones de la Suisse, et le Liechtenstein[5]. L'exception la plus notable était le Royaume-Uni, principalement anglo-saxon, dont il n'était pas projeté qu'il fût réduit à être une province allemande mais plutôt qu'il deviendrait un partenaire maritime allié des Allemands[6].

De surcroît, sa frontière occidentale avec la France devait revenir à celle de l'ancien Saint-Empire romain, ce qui aurait signifié l'annexion complète de toute la Wallonie, la Romandie (Suisse francophone) et d'importants territoires du nord et de l'est de la France[7]. Lorsque l'allié des Allemands que constituait l'Italie fasciste pendant cette guerre fit reddition du conflit en 1943, il fut même prévu que d'importants territoires de l'Italie du nord fussent directement inclus. Une extension territoriale massive en Europe de l'Est sous domination allemande devait aussi avoir lieu, dans laquelle les peuples des pays germaniques allaient être « encouragés » à s'installer (voir Lebensraum).

Fondement idéologique[modifier | modifier le code]

Théories raciales[modifier | modifier le code]

L'idéologie raciale nazie regardait les peuples germaniques d'Europe comme appartenant à un sous-groupe nordique racialement supérieur de la race aryenne, qui étaient regardés comme les seuls vrais porteurs de culture (![]() traduction, en anglais "culture-bearers") de la société civilisée[8]. Ces peuples étaient vus comme soit « vrais peuples germaniques » qui avaient « perdu leur sens de fierté raciale », soit comme des parents racialement proches des Allemands[9]. Le dictateur allemand Adolf Hitler croyait aussi que les anciens Grecs et les Romains étaient les ancêtres raciaux des Allemands et les premiers portes-flammes (

traduction, en anglais "culture-bearers") de la société civilisée[8]. Ces peuples étaient vus comme soit « vrais peuples germaniques » qui avaient « perdu leur sens de fierté raciale », soit comme des parents racialement proches des Allemands[9]. Le dictateur allemand Adolf Hitler croyait aussi que les anciens Grecs et les Romains étaient les ancêtres raciaux des Allemands et les premiers portes-flammes (![]() traduction, en anglais "torchbearers") de l'art et de la culture « nordique-grecque »[10][11]. Il exprimait particulièrement son admiration de la Sparte ancienne, déclarant que ce fut l'État racialement le plus pur[12] :

traduction, en anglais "torchbearers") de l'art et de la culture « nordique-grecque »[10][11]. Il exprimait particulièrement son admiration de la Sparte ancienne, déclarant que ce fut l'État racialement le plus pur[12] :

« L'assujettissement de 350 000 Hilotes par 6 000 Spartiates fut seulement possible grâce à la supériorité raciale des Spartiates. » Les Spartiates avaient créé « le premier État racialiste. »

— Adolf Hitler, [13].

De plus, le concept hitlérien de « Germanique » ne se référait pas simplement à un groupe ethnique, culturel ou linguistique mais aussi à un groupe biologique distinct, le « sang germanique » supérieur qu'il voulait sauver du contrôle des ennemis de la race aryenne. Il déclara que l'Allemagne possédait plus de ces « éléments germaniques » que tout autre pays dans le monde, qu'il estimait à « quatre cinquièmes de notre peuple »[14].

« Quel que soit l'endroit où du sang germanique sera trouvé dans le monde, nous prendrons ce qui est bon pour nous-mêmes. Avec ce que les autres ont laissé ils seront incapables de s'opposer à l'empire germanique. »

— Adolf Hitler, [15]

Selon les Nazis, en plus des peuples germaniques, les individus de nationalité d'apparence non-germanique comme les Français, les Polonais, les Wallons, les Tchèques etc. pourraient en réalité posséder du précieux sang germanique, spécialement s'il venaient de milieux aristocratique ou paysan[15]. Afin de « récupérer » ces éléments germaniques « manquants », il fallait les rendre conscients de leur ascendance germanique à travers le processus de germanisation (le terme utilisé par les Nazis pour ce processus était Umvolkung, « restauration de la race »)[15]. Si la « récupération » était impossible, ces individus devaient être détruits pour empêcher l'ennemi d'utiliser leur sang supérieur contre la race aryenne[15]. Un example de ce type de germanisation nazie est l'enlèvement de « racialement précieux » enfants d'Europe de l'est.

Dans la toute première page de Mein Kampf Hitler déclara ouvertement sa conviction qu'un « sang commun appartient à un Reich commun », élucidant (![]() traduction, en anglais "elucidating") la notion que la qualité innée de race (comme le mouvement nazi le percevait) devrait être prioritaire sur les concepts « artificiels » tels que l'identité nationale (y compris les identités régionales allemandes comme les Prussiens et les Bavarois) comme le facteur décisif pour savoir quel peuple étaient digne d'être assimilés au sein d'un Grand État racial allemand (Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer)[16]. Une partie des méthodes stratégiques qu'Hitler choisit pour garantir la présente et future suprématie de la race aryenne (qui, selon Hitler, « approchait graduellement l'extinction »[17]) était d'en finir avec ce qu'il décrivait comme le <<

traduction, en anglais "elucidating") la notion que la qualité innée de race (comme le mouvement nazi le percevait) devrait être prioritaire sur les concepts « artificiels » tels que l'identité nationale (y compris les identités régionales allemandes comme les Prussiens et les Bavarois) comme le facteur décisif pour savoir quel peuple étaient digne d'être assimilés au sein d'un Grand État racial allemand (Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer)[16]. Une partie des méthodes stratégiques qu'Hitler choisit pour garantir la présente et future suprématie de la race aryenne (qui, selon Hitler, « approchait graduellement l'extinction »[17]) était d'en finir avec ce qu'il décrivait comme le <<![]() traduction "small state rubbish">> (kleinstaatengerümpel, voir aussi kleinstaaterei) en Europe afin d'unir tous ces pays nordiques en une communauté raciale unifiée[18]. À partir de 1921 il a plaidé pour la création d'un « Reich germanique de la Nation allemande »[2].

traduction "small state rubbish">> (kleinstaatengerümpel, voir aussi kleinstaaterei) en Europe afin d'unir tous ces pays nordiques en une communauté raciale unifiée[18]. À partir de 1921 il a plaidé pour la création d'un « Reich germanique de la Nation allemande »[2].

« Ce fut le continent qui apporta la civilisation à la Grande-Bretagne et à son tour lui permit de coloniser de grandes étendues dans le reste du monde. L’Amérique est impensable sans l'Europe. Pourquoi n'aurions-nous pas le pouvoir nécessaire de devenir un des centres d'attraction mondiaux ? Cent vingt millions de personnes d'origine germanique – s'ils ont consolidé leur position que ce sera un pouvoir à qui personne dans le monde ne pourra résister. Les pays qui forment le monde germanique ont tout à gagner de ceci. Je peux voir cela dans mon propre cas. Mon pays natal est une des plus belles régions du Reich, mais que pourrait-il faire s'il était laissé à ses propres moyens ? Il est impossible de développer ses talents dans des pays comme l'Autriche ou la Saxe, le Danemark ou la Suisse. Il n'y a pas de fondement. C'est pourquoi il est heureux (fortunate en anglais, NDR) que de potentiels nouveaux espaces soient encore ouverts aux peuples germaniques. »

— Adolf Hitler, 1942.[19]

Nom[modifier | modifier le code]

Le nom choisi pour l'empire en projet était une référence délibérée au Saint-Empire romain (de la Nation allemande[20]) qui existait au Moyen Âge, connu comme le Premier Reich dans l'historiographie nazie[21]. Différents aspects de la <<legacy>> de cet empire médiéval dans l'histoire allemande étaient aussi bien célébrés et <<derided>> par le gouvernement nazi. L'Empereur franc Charlemagne était admiré par Hitler pour sa "créativité culturelle", ses pouvoirs d'organisation, et sa renonciation aux droits de l'individu[21]. Il critiqua cependant les Saints Empereurs romains de ne pas avoir poursuivi une Ostpolitik (politique vers l'Est) <<resembling his own>>, <<while>> étant politiquement concentré exclusivement sur le sud[21]. Après l'Anschluss, Hitler ordonna que les anciens regalia impériaux (la Couronne impériale, l'Épée impériale, la Croix de Lothaire, la Sainte Lance et d'autres <<items>>) résidant à Vienne fussent transférés à Nuremberg, où ils étaient gardé entre 1424 et 1796[22]. Nuremberg, en plus d'être l'ancienne capitale inofficielle du Saint-Empire romain, était aussi <<the place of the Nazi party rallies>>. Le transfert des regalia fut donc fait à la fois pour légitimer l'Allemagne de Hitler comme le successeur de l'"Ancien Reich", mais aussi affaiblir Vienne, l'ancienne résidence impériale[23].

Après l'occupation allemande de la Bohême en 1939, Hitler déclara que le Saint-Empire avait été "ressuscité", bien qu'il maintenait secrètement que son propre empire était meilleur que le vieil empire "romain"[24]. Contrairement à l'"inconfortablement internationaliste empire catholique de Barberousse", le Reich germanique de la Nation allemande serait raciste et nationaliste[24]. Plutôt qu'un retour aux valeurs du Moyen-Âge, son établissement devait être "<<a push forward>> vers un nouvel âge d'or, dans lequel les meilleurs aspects du passé seraient combinés avec une pensée moderne raciste et nationaliste"[24].

Les frontières historiques du Saint-Empire étaient aussi utilisées comme fondement pour le révisionnisme territorial par les Nazis, <<laying>> revendications sur des territoires et des États qui ont un jour fait partie de celui-ci. Même avant la guerre, Hitler avait rêvé de renverser la Paix de Westphalie, qui avait donné aux territoires de l'Empire une souveraineté presque complète[25]. Le , le Ministre du Reich de la Propagande Joseph Goebbels écrit dans son journal that the "total liquidation" of this historic treaty was the "great goal" of the Nazi regime,[25] and that since it had been signed in Münster, it would also be officially repealed in the same city[26].

Pangermanisme contre pangermanicisme[modifier | modifier le code]

Bien que prévoyant d'accorder aux autres « Germaniques » d'Europe un statut racialement supérieur au côté des Allemands eux-mêmes en anticipation d'un ordre racio-politique post-guerre, les Nazis n'avaient cependant pas l'intention de donner aux populations sujettes de ces pays un quelconque droit national propre[8]. Les autres pays germaniques étaient plus vus comme des extensions de l'Allemagne plutôt que des unités individuelles en un quelconque sens[8], et les Allemands étaient devaient sans équivoque rester la « source de force la plus puissante [de l'empire], aussi bien d'un "standpoint" idéologique que militaire »[19]. Même Heinrich Himmler, qui parmi les "senior" Nazis défendait de la façon la plus claire le concept, ne pouvait pas se débarasser de l'idée d'une distinction entre << German Volk >> et << Germanic Völker >>[27]. Le journal officiel des SS, Das Schwarze Korps, n'a jamais réussi à réconcilier la contradiction entre « fraternité » germanique et supériorité allemande[27]. Il était également interdit aux membres des partis de type nazi dans les pays germaniques d'assister aux réunions publiques du Parti nazi quand ils étaient en visite en Allemagne. Après la Bataille de Stalingrad <<this ban was lifted>>, mais seulement si les <<attendees made prior notice>> de leur arrivée afin que <<the events' speakers>> puissent être avertis en avance de ne pas faire de remarque <<disparaging>> à propos du pays d'origine[28].

Bien qu'Hitler lui-même et << Himmler's SS advocated for >> un Empire pangermanique, l'objectif n'était pas universellement <<held>> dans le régime nazi[29]. Goebbels et le Ministère des Affaires étrangères du Reich sous Joachim von Ribbentrop <<inclined more towards>> une idée d'un bloc continental sous domination allemande, comme cela était représenté par le Pacte anti-Comintern et le <<earlier>> concept de Mitteleuropa.

Germanic mysticism[modifier | modifier le code]

Modèle:See There were also disagreements within the Nazi leadership on the spiritual implications of cultivating a 'Germanic history' in their ideological program. Hitler was highly critical of Himmler's esoteric völkisch interpretation of the 'Germanic mission'. When Himmler denounced Charlemagne in a speech as "the butcher of the Saxons", Hitler stated that this was not a 'historical crime' but in fact a good thing, for the subjugation of Widukind had brought Western culture into what eventually became Germany.[30] He also disapproved of the pseudoarchaeological projects which Himmler organized through his Ahnenerbe organization, such as excavations of pre-historic Germanic sites:

In an attempt to eventually supplant Christianity with a new religion more amenable to Nazi ideology Himmler, together with Alfred Rosenberg, sought to replace it with Germanic paganism, such as renewed worship of the deity Wōden.[31] For this purpose they had ordered the construction of sites for the worship of Germanic cults in order to exchange Christian rituals for 'Nordic' consecration ceremonies, which included different marriage and burial rites.[31] In Heinrich Heims' Adolf Hitler, Monologe im FHQ 1941-1944 (several editions, here Orbis Verlag, 2000), Hitler is quoted as having said on 14 October 1941: "It seems to be inexpressibly stupid to allow a revival of the cult of Odin/Wotan. Our old mythology of the gods was defunct, and incapable of revival, when Christianity came...the whole world of antiquity either followed philosophical systems on the one hand, or worshipped the gods. But in modern times it is undesirable that all humanity should make such a fool of itself."

Establishment strategy[modifier | modifier le code]

The goal was first proclaimed publicly in the 1937 Nuremberg Rallies.[32] Hitler's last speech at this event ended with the words "The German nation has after all acquired its Germanic Reich", which elicited speculation in political circles of a 'new era' in Germany's foreign policy.[32] Several days before the event Hitler took Albert Speer aside when both were on their way to the former's Munich apartment with an entourage, and declared to him that "We will create a great empire. All the Germanic peoples will be included in it. It will begin in Norway and extend to northern Italy.[nb 1] I myself must carry this out. If only I keep my health!"[32] On April 9, 1940, as Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in Operation Weserübung, Hitler announced the establishment of the Germanic Reich:

The establishment of the empire was to follow the model of the Austrian Anschluss of 1938, just carried out on a greater scale.[34] Goebbels emphasized in April 1940 that the annexed Germanic countries would have to undergo a similar "national revolution" as Germany herself did after the Machtergreifung, with an enforced rapid social and political "co-ordination" in accordance with Nazi principles and ideology (Gleichschaltung)[34].

The ultimate goal of the Gleichschaltung policy pursued in these parts of occupied Europe was to destroy the very concepts of individual states and nationalities, just as the concept of a separate Austrian state and national identity was repressed after the Anschluss through the establishment of new state and party districts.[35] The new empire was to no longer be a nation-state of the type that had emerged in the 19th century, but instead a "racially pure community".[25] It is for this reason that the Nazi occupiers had no interest in transferring real power to the various far-right nationalistic movements present in the occupied countries (such as Nasjonal Samling, the NSB, etc.) except for temporary reasons of Realpolitik, and instead actively supported radical collaborators who favored pan-Germanic unity (i.e. total integration to Germany) over provincial nationalism (for example DeVlag).[36] Unlike Austria and the Sudetenland however, the process was to take considerably longer.[37] Eventually these nationalities were to be merged with the Germans into a single ruling race, but Hitler stated that this prospect lay "a hundred or so years" in the future. During this interim period it was intended that the 'New Europe' would by run by Germans alone.[27] According to Speer, while Himmler intended to eventually Germanize these peoples completely, Hitler intended not to "infringe on their individuality" (that is, their native languages), so that in the future they would "add to the diversity and dynamism" of his empire.[38] The German language would be its lingua franca however, likening it to the status of English in the British Commonwealth[38].

A primary agent used in stifling the local extreme nationalist elements was the Germanic SS, which initially merely consisted of local respective branches of the Allgemeine-SS in Belgium, Netherlands and Norway.[39] These groups were at first under the authority of their respective pro-Nazi national commanders (Quisling, Mussert and De Clercq), and were intended to function within their own national territories only.[39] During the course of 1942, however, the Germanic SS was further transformed into a tool used by Himmler against the influence of the less extreme collaborating parties and their SA-style organizations, such as the Hird in Norway and the Weerbaarheidsafdeling in the Netherlands.[39][40] In the post-war Germanic Empire, these men were to form the new leadership cadre of their respective national territories.[41] To emphasize their pan-Germanic ideology, the Norges SS was now renamed the Germanske SS Norge, the Nederlandsche SS the Germaansche SS in Nederland and the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen the Germaansche SS in Vlaanderen. The men of these groups no longer swore allegiance to their respective national leaders, but to the germanischer Führer ("Germanic Führer"), Adolf Hitler[39][40]:

This title was assumed by Hitler on 23 June 1941, at the suggestion of Himmler.[42] On 12 December 1941 the Dutch fascist Anton Mussert also addressed him in this fashion when he proclaimed his allegiance to Hitler during a visit to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[43] He had wanted to address Hitler as Führer aller Germanen ("Führer of all Germanics"), but Hitler personally decreed the former style.[42] Historian Loe de Jong speculates on the difference between the two: Führer aller Germanen implied a position separate from Hitler's role as Führer und Reichskanzler des Grossdeutschen Reiches ("Führer and Reich Chancellor of the Greater German Reich"), while germanischer Führer served more as an attribute of that main function.[43] As late as 1944 occasional propaganda publications continued to refer to him by this unofficial title as well however.[44] Mussert held that Hitler was predistened to become the Führer of Germanics because of his congruous personal history: Hitler originally was a Austrian national, who enlisted in the Bavarian army and lost his Austrian citizenship. He thus remained stateless for seven years, during which, according to Mussert, he was "the Germanic leader and nothing else"[45].

The Swastika Flag was to be used as a symbol to represent not only the National Socialist movement, but also the unity of the Nordic-Germanic peoples into a single state.[46] Using the Unification of Germany as an analogy, it was held that since the flag of the Kingdom of Prussia could not have been imposed on the other German states that would together form the new German Empire of 1871, so too could the German national flag (referring to the Imperial tricolour, as the Nazis had banned the black-red-gold version) not be imposed on the other Germanic countries of Europe[46].

Hitler had long intended to architecturally reconstruct the German capital Berlin into a new imperial metropolis, which he decided in 1942 to rename Germania upon its scheduled completion in 1950. The name was specifically chosen to make it the clear central point of the envisioned Germanic empire, and to re-enforce the notion of a united Germanic-Nordic state upon the Germanic peoples of Europe[47].

Policies undertaken in the countries[modifier | modifier le code]

Low countries[modifier | modifier le code]

The German plans of annexation were more advanced for the Low Countries than for the Nordic states, due in part because of their closer geographical proximity as well as cultural and ethnic ties to Germany. Luxembourg and Belgium were both formally annexed into the Nazi state during World War II, in 1942 and 1944 respectively, the latter as the new Reichsgaue of Flandern and Wallonien (the proposed third one, Brabant, was not implemented in this arrangement) and a Brussels District. On April 5 1942, while having dinner with an entourage including Heinrich Himmler, Hitler declared his intention that the Low Countries would be included whole into the Reich, at which point the Greater German Reich would be reformed into the Germanic Reich (simply "the Reich" in common parlance) to signify this change[19].

In October 1940 Hitler disclosed to Benito Mussolini that he intended to leave the Netherlands semi-independent because he wanted that country to retain its overseas colonial empire after the war.[48] This factor was removed after the Japanese took over the Netherlands East Indies, the primary component of that domain.[48] The resulting German plans for the Netherlands suggested its transformation into a Gau Westland, which would eventually be further broken-up into five new Gaue or gewesten (historical Dutch term for a type of sub-national polity). Fritz Schmidt, a high Nazi official in the occupied Netherlands who hoped to become the Gauleiter of this new province on Germany's western periphery stated that it could even be called Gau Holland, as long as the Wilhelmus (the Dutch national anthem) and similar patriotic symbols were to be forbidden.[49] Rotterdam, which had actually been largely destroyed in the course of the 1940 invasion was to be rebuilt as the most important port-city in the "Germanic area" due to its situation at the mouth of the Rhine river[50].

Himmler's personal masseur Felix Kersten claimed that the former even contemplated resettling the entire Dutch population, some 8 million people in total at the time, to agricultural lands in the Vistula and Bug River valleys of German-occupied Poland as the most efficient way of facilitating their immediate Germanization.[51] In this eventuality he is alleged to have further hoped to establish an SS Province of Holland in vacated Dutch territory, and to distribute all confiscated Dutch property and real estate among reliable SS-men.[52] However this claim was shown to be a myth by Loe de Jong in his book Two Legends of the Third Reich[53].

The position in the future empire of the Frisians, another Germanic people, was discussed on 5 April 1942 in one of Hitler’s many wartime dinner-conversations.[19] Himmler commented that there was ostensibly no real sense of community between the different indigenous ethnic groups in the Netherlands. He then stated that the Dutch Frisians in particular seemed to hold no affection for being part of a nation-state based on the Dutch national identity, and felt a much greater sense of kinship with their German Frisian brethren across the Ems River in East Frisia, an observation Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel agreed with based on his own experiences.[19] Hitler determined that the best course of action in that case would be to unite the two Frisian regions on both sides of the border into a single province, and would at a later point in time further discuss the topic with Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the governor of the German regime in the Netherlands.[19] By late May of that year these discussions were apparently concluded, as on the 29th he pledged that he would not allow the West-Frisians to remain part of Holland, and that since they were "part of the exact same race as the people of East Frisia" had to be joined into one province[54].

Hitler considered Wallonia to be "in reality German lands" (although Himmler initially protested against the inclusion of 'racially inferior' French and Walloon volunteers in the Waffen-SS) which were gradually detached from the Germanic territories by the French Romanization of the Walloons, and that Germany thus had "every right" to take these back.[7] Before the decision was made to include Wallonia in its entirety, several smaller areas straddling the traditional Germanic-Romance language border in Western Europe were already considered for inclusion. These included the small Lëtzebuergesh-speaking area centred around Arlon,[55] as well as the Low Dietsch-speaking region west of Eupen (the so-called Platdietse Streek) around the city of Limbourg, historical capital of the Duchy of Limburg[56].

Nordic countries[modifier | modifier le code]

Modèle:See After their invasion in Operation Weserübung, Hitler vowed that he would never again leave Norway,[50] and favored annexing Denmark as a German province even more due to its small size and relative closeness to Germany.[57] Himmler's hopes were an expansion of the project so that Iceland would also be included among the group of Germanic countries which would have to be gradually incorporated into the Reich.[57] He was also among the group of more esoteric Nazis who believed either Iceland or Greenland to be the mystical land of Thule, a purported original homeland of the ancient Aryan race.[58] From a military point of view, the Kriegsmarine command hoped to see the Spitsbergen, Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Isles and possibly the Shetland Isles (which were also claimed by the Quisling regime[59]) under its domination to guarantee German naval access to the mid-Atlantic[60].

The erection of a new German metropolis (with 300.000 inhabitants) called Nordstern ("North Star") next to the Norwegian city of Trondheim was prepared for, to be accompanied by a major naval base that was expected to become Germany's largest one in all of Europe.[50][61] This city was to be connected to Germany proper by an Autobahn across the Little and Great Belts and house an art museum for the northern part of the Germanic empire, housing "only works of German artists."[62]

Sweden's future subordination into the Nazis' 'New Order' was considered by the regime.[63] Himmler stated that the Swedes were the "epitome of the Nordic spirit and the Nordic man", and looked forward to incorporating central and southern Sweden to the Germanic Empire.[63] Northern Sweden, with its Finnish minority, along with the Norwegian port of Kirkenes Himmler offered to Finland, although this suggestion was rejected by Finnish Foreign Minister Witting.[64][65] Felix Kersten, claimed that Himmler had expressed regret that Germany had not occupied Sweden during Operation Weserübung, but was certain that this error was to be rectified after the war.[66] In April 1942, Goebbels expressed similar views in his diary, writing that Germany should have occupied the country during its campaign in the north, as "this state has no right to national existence anyway".[67] In 1940, Hermann Göring suggested that Sweden's future position in the Reich was similar to that of Bavaria in the German Empire.[63] The ethnically Swedish Åland Islands, which were awarded to Finland by the League of Nations in 1921, were likely to join Sweden in the Germanic Empire. In the spring of 1941, the German military attaché in Helsinki reported to his Swedish counterpart that Germany would need transit rights through Sweden for the imminent invasion of the Soviet Union, and in the case of finding her cooperative would permit the Swedish annexation of the islands.[68] Hitler did veto the idea of a complete union between the two states of Sweden and Finland, however[69].

Despite the majority of its people being of Finno-Ugric origin, Finland was given the status of being an "honorary Nordic nation" (from a Nazi racial perspective, not a national one) by Hitler as reward for its military importance in the ongoing conflict against the Soviet Union.[69] The Swedish-speaking minority of the country, who in 1941 comprised 9.6% of the total population, were considered Nordic and were initially preferred over Finnish speakers in recruitment for the Finnish Volunteer Battalion of the Waffen-SS.[70] Finland's Nordic status did not mean however that it was intended to be absorbed into the Germanic Empire, but instead expected to become the guardian of Germany’s northern flank against the hostile remnants of a conquered USSR by attaining control over Karelian territory, occupied by the Finns in 1941.[69] Hitler also considered the Finnish and Karelian climates unsuitable for German colonization.[71] Even so the possibility of Finland's eventual inclusion as a federated state in the empire as a long-term objective was mulled over by Hitler in 1941, but by 1942 he seems to have abandoned this line of thinking.[71] According to Kersten, as Finland signed an armistice with the Soviet Union and broke off diplomatic relations with her former brother-in-arms Germany in September 1944, Himmler felt remorse for not eliminating the Finnish state, government and its "masonic" leadership sooner, and transforming the country into a "National Socialist Finland with a Germanic outlook"[72].

Switzerland[modifier | modifier le code]

The same implicit hostility toward neutral nations such as Sweden was also held towards Switzerland. Goebbels noted in his diary on December 18, 1941 that "It would be a veritable insult to God if they [the neutrals] would not only survive this war unscathed while the major powers make such great sacrifices, but also profit from it. We will certainly make sure that this will not happen."[73]

The Swiss people were seen by Nazi ideologists as a mere off-shoot of the German nation, although one led astray by decadent Western ideals of democracy and materialism.[74] Hitler decried the Swiss as "a misbegotten branch of our Volk" and the Swiss state as "a pimple on the face of Europe" deeming them unsuitable for settling the territories that the Nazis expected to colonize in Eastern Europe[75].

Himmler discussed plans with his subordinates to integrate at least the German-speaking parts of Switzerland completely with the rest of Germany, and had several persons in mind for the post of a Reichskommissar for the 're-union' of Switzerland with the German Reich (in analogy to the office that Josef Bürckel held after Austria's absorption into Germany during the Anschluss). Later this official was to subsequently become the new Reichsstatthalter of the area after completing its total assimilation.[5][76] In August 1940, Gauleiter of Westfalen-South Josef Wagner and the Minister President of Baden Walter Köhler spoke in favor of the amalgamation of Switzerland to Reichsgau Burgund (see below) and suggested that the seat of government for this new administrative territory should be the dormant Palais des Nations in Geneva[77].

Operation Tannenbaum, a military offensive intended to occupy all of Switzerland, most likely in co-operation with Italy (which itself desired the Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland), was in the planning stages during 1940-1941. Its implementation was seriously considered by the German military after the armistice with France, but it was definitively shelved after the start of Operation Barbarossa had directed the attention of the Wehrmacht elsewhere[78].

Eastern France[modifier | modifier le code]

Modèle:See After the German victory over France, the regime took the initial steps for the "restitution" of the Holy Roman Empire's western border from the time of Charles V. Under the auspices of State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart the Reich Interior Ministry already produced an initial memo for the planned annexation of a strip of eastern France in June 1940, stretching from the mouth of the Somme to Lake Geneva,[79] and on July 10, 1940 Himmler toured the region to inspect its Germanization potential.[25] According to documents produced in December 1940, the annexed territory would consist of nine French departments, and the Germanization action would require the settlement of a million Germans from "peasant families".[25] Himmler decided that South Tyrolean emigrants (see South Tyrol Option Agreement) would be used as settlers, and the towns of the region would receive South Tyrolean place-names such as Bozen, Brixen, Meran, and so on.[80] By 1942 Hitler had, however, decided that the South Tyroleans would be instead used to settle the Crimea, and Himmler regretfully noted "For Burgundy, we will just have to find another [Germanic] ethnic group."[81]

Hitler claimed French territory even beyond the historical border of the Holy Roman Empire. He stated that in order to ensure German hegemony on the continent, Germany must "also retain military strong points on what was formerly the French Atlantic coast" and emphasized that "nothing on earth would persuade us to abandon such safe positions as those on the Channel coast, captured during the campaign in France and consolidated by the Organisation Todt."[82] Several major French cities along the coast were given the designation Festung ("fortress"; "stronghold") by Hitler, such as Le Havre, Brest and St. Nazaire,[83] suggesting that they were to remain under permanent post-war German administration.

Northern Italy[modifier | modifier le code]

Modèle:See Initially intending to use the Germans of South Tyrol as settlers for Generalplan Ost, the Italian surrender made it possible for Germany to occupy much of Italy, and re-arrange the provinces of Trentino, Belluno and South Tyrol into the military district Alpenvorland and the provinces of Friuli, Fiume, Pola, Gorizia, Trieste and Lubiana into the district Adriatisches Küstenland.[84] Both districts were to be eventually annexed into the Germanic Reich, in spite of Hitler's admiration and respect for the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.[84] Hitler had stated that the art of Northern Italy was "nothing but pure German",[85] and Nazi scholars viewed that the Romansh, Ladin and Friulian minorities of the two districts were racially, historically and culturally a part of the Germanic world[86].

Further extension of the Germanic Reich's southern border was considered. According to Goebbels, Hitler had expressed that the border should extend to those of the region of Veneto.[84] Veneto was to be included into the Reich in an "autonomous form", and to benefit from the post-war influx of German tourists.[84] At the time when Italy was on the verge of declaring an armistice with the Allies, Himmler declared to Felix Kersten that Northern Italy, along with the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, was "bound to eventually be included in Greater Germany anyway".[87] The former Austrian territory of Lombardy was not specifically mentioned as an annexation target by either Goebbels or Himmler, but seems to have been designed to eventually join Veneto in the Germanic Reich.[88] Hitler speaks favorably of the region's Germanic character in Table Talk and laments his "predecessors'" inability of consolidating the Holy Roman Empire's southernmost lands.[89] In a supplementary OKW order dated 10 September 1943, Hitler decrees on the establishment of further Operational Zones in Northern Italy, which were the stretch all the way to the French border.[90] Unlike Alpenvorland and Küstenland, these zones did not immediately receive high commissioners (oberster kommissar) as civilian advisors, but were military regions where the commander was to exercise power on behalf of Army Group B.[90] Operation zone Nordwest-Alpen or Schweizer Grenze was located between the Stelvio Pass and Monte Rosa and was to contain wholly the Italian provinces of Sondrio and Como and parts of the provinces of Brescia, Varese, Novara and Vercelli.[91] The zone of Französische Grenze was to encompass areas west of Monte Rosa and was to incorporate the province of Aosta and a part of the province of Turin, and presumably also the provinces of Cuneo and Imperia[91].

Îles de l'Atlantique[modifier | modifier le code]

Pendant l'été 1940, Hitler envisagea la possibilité d'occuper les Açores, le Cap-Vert et Madère, portugais, ainsi que les îles Canaries, espagnoles, pour priver les Britanniques d' a staging ground pour des actions militaires contre l'Europe sous contrôle nazi[17],[92]. Hitler souleva à nouveau la question en septembre 1940 lors d'une discussion avec le ministre espagnol des Affaires étrangères Ramón Serrano Súñer, lui proposant alors que l'Espagne transfère l'une des îles Canaries pour l'usage de l'Allemagne en échange du Maroc français[92]. Bien que l'intérêt de Hitler pour les îles de l'Atlantique doive être compris dans le cadre imposé par la situation militaire de 1940, il n'avait jamais eu l'intention de libérer ces importantes bases navales du contrôle allemand[92].

L'Ahnenerbe (« Héritage ancestral ») de Himmler comprenait des théories pseudoarchéologiques des savants Hermann Wirth et Otto Huth, qui fantasmaient sur le fait que le Cap-Vert et les îles Canaries étaient les seules parties du continent perdu Atlantide demeurant hors de l'océan[93]. Huth, sous le patronage de l'Ahnenerbe, prévit une expédition archéologique aux îles Canaries dans le but de trouver des artéfacts des Nord-Atlantes antédiluviens[93]. Il estimait en outre que les indigènes des îles étaient les restes d'une « ancienne civilisation nordique » qui s'était « épanouie tranquillement sur les îles heureuses jusqu'à ce qu'elle soit détruite »[93].

Role of the British Isles in the Germanic order[modifier | modifier le code]

The one country that was not included in the Pan-Germanic unification aim was the United Kingdom,[94] in spite of its near-universal acceptance by the Nazi government as being part of the Germanic world.[95] Leading Nordic ideologist Hans F. K. Günther theorized that the Anglo-Saxons had been more successful than the Germans in maintaining racial purity, thanks to Britain's island nature, with interbreeding between the Germanic conquerors and the subjugated Celtic nations being only marginal in effect.[96] Furthermore, the coastal and island areas of Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and Wales had received additional Nordic blood through Norse raids and colonization during the Viking Age, and the Anglo-Saxons of Eastern and Northern England had been under Danish rule in the 9th and 10th centuries.[96] Günther referred to this historical process as Aufnordung ("additional nordification"), which finally culminated in the Norman conquest of England in 1066.[96] Britain was thus a nation created by struggle and the survival of the fittest among the various Aryan peoples of the isles, and was able to pursue global conquest and empire-building because of its superior racial heredity born through this development[97].

Hitler professed an admiration for the imperial might of the British Empire in Zweites Buch as proof of the racial superiority of the Aryan race,[98] hoping that Germany would emulate British "ruthlessness" and "absence of moral scruples" in establishing its own colonial empire in Eastern Europe.[99] One of his primary foreign policy aims throughout the 1930s was to establish a military alliance with both the English (Hitler conflated England with Britain and the United Kingdom in his writings and speeches) as well as the Italians to neutralize France as a strategic threat to German security for eastward expansion. In this arrangement the two "kindred folks" were to divide the world between each other with Germany dominating continental Europe, while England would reign supreme over the world’s oceans.

When it became apparent to the Nazi leadership that the United Kingdom was not interested in a military alliance, anti-British policies were adopted to ensure the attainment of Germany’s war aims. Even during the war however, hope remained that Britain would in time yet become a reliable German ally.[100] Hitler preferred to see the British Empire preserved as a world power, because its break-up would benefit other countries far more than it would Germany, particularly the United States and Japan.[100] In fact, Hitler's strategy during 1935-1937 for winning Britain over was based on a German guarantee of defence of the British Empire.[101] After the war, Ribbentrop testified that in 1935 Hitler had promised to deliver twelve German divisions to the disposal of Britain for maintaining the integrity of her colonial possessions[102].

The continued military actions against Britain after the fall of France had the strategic goal of making Britain 'see the light' and conduct an armistice with the Axis powers, with July 1, 1940 being named by the Germans as the "probable date" for the cessation of hostilities.[103] On May 21, 1940, Franz Halder, the head of the Army General Staff, after a consultation with Hitler concerning the aims envisaged by the Führer during the present war, wrote in his diary: "We are seeking contact with Britain on the basis of partitioning the world"[104].

One of Hitler's sub-goals for the invasion of Russia was to win over Britain to the German side. He believed that after the military collapse of the USSR, "within a few weeks" Britain would be forced either into a surrender or else come to join Germany as a "junior partner" in the Axis.[105] Britain's role in this alliance was reserved to support German naval and aerial military actions against the USA in a fight for world supremacy conducted from the Axis power bases of Europe, Africa and the Atlantic.[106] On August 8, 1941, Hitler stated that he looked forward to the eventual day when "England and Germany [march] together against America" and on January 7, 1942 he daydreamed that it was "not impossible" for Britain to quit the war and join the Axis side, leading to a situation where "it will be a German-British army that will chase the Americans from Iceland".[107] Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg hoped that after the victorious conclusion of the war against the USSR, Englishmen, along with other Germanic nationalities, would join the German settlers in colonizing the conquered eastern territories[15].

From a historical perspective Britain’s situation was likened to that which the Austrian Empire found itself in after it was defeated by the Kingdom of Prussia in the Battle of Königgratz in 1866.[100] As Austria was thereafter formally excluded from German affairs, so too would Britain be excluded from continental affairs in the event of a German victory. Yet afterwards, Austria-Hungary became a loyal ally of the German Empire in the pre-World War I power alignments in Europe, and it was hoped that Britain would come to fulfill this same role[100].

Îles de la Manche[modifier | modifier le code]

Les îles Anglo-Normandes (îles de la Manche) devait être intégrées de façon permanente dans l'Empire germanique[108]. Le 22 juillet 1940, Hitler déclara qu'après la guerre les îles passeraient sous le contrôle du Deutsche Arbeitsfront (« Front allemand du travail ») de Robert Ley et seraient transférées à l'organisation de loisirs Kraft durch Freude (« La force par la joie »)[109]. Le savant nazi Karl Heinz Pfeffer visita les îles en 1941 et recommanda aux occupants allemands de faire appel à l'héritage normand des habitants et de traiter les îles comme des « micro-États germaniques » dont l'union à la Grande-Bretagne n'avait été qu'un accident de l'histoire[110]. Il comparait cette politique pour les îles de la Manche à celle mise en place par les Britanniques à Malte, où la langue maltaise avait été « artificiellement » soutenue contre l'italien[110].

Irlande[modifier | modifier le code]

Un plan d'opération militaire destiné à envahir l'Irlande en soutient à l'opération Sea Lion fut élaboré par l'Allemagne en . L'Irlande occupée devait être gouvernée avec la Grande-Bretagne par un système administratif temporaire divisé en six commandements militaro-économiques, dont un des quartiers généraux serait situé à Dublin[111]. La future position de l'Irlande dans le Nouvel Ordre est incertaine, mais on sait que Hitler aurait réunifié (en) l'Irlande[112].

Expected participation in the colonization of Eastern Europe[modifier | modifier le code]

Despite the pursued aim of pan-Germanic unification, the primary goal of Nazi Germany’s territorial expansionism was to acquire sufficient Lebensraum in Eastern Europe for the "Aryan race". The primary objective of this aim was to transform Germany into a complete economic autarky, the end-result of which would be a state of continent-wide German hegemony over Europe. This was to be accomplished through the enlargement of the territorial base of the German state and the expansion of the German population,[113] and the wholesale extermination of the indigenous Slavic and Baltic inhabitants[114].

Because of their perceived racial worth, the Nazi leadership was enthusiastic at the prospect of "recruiting" people from the Germanic countries to also settle these territories after the Slavic inhabitants would have been exterminated or otherwise driven out.[115] The racial planners were partly motivated in this because studies indicated that Germany would likely not be able to recruit enough colonial settlers for the eastern territories from its own country and other Germanic groups would therefore be required.[114] Hitler insisted however that German settlers would have to dominate the newly colonized areas.[9] Himmler's original plan for the Hegewald settlement was to settle Dutch and Scandinavians there in addition to Germans, which was unsuccessful[116].

Développement ultérieur[modifier | modifier le code]

Après l'invasion allemande de l'URSS en , la préoccupation de Hitler concernant le plan pangermanique commença à fade, bien que l'idée ne fût jamais abandonnée. Étant donné que les volontaires étrangers de la Waffen-SS étant pour une part de plus en plus importante d'origine non germanique, en particulier après la bataille de Stalingrad, la proposition d'un Grand Empire germanique laissa la place au sein du leadership de l'organisation (par exemple Felix Steiner) au concept d'une union européenne d'États s'auto-gouvernant, unifiés par l'hégémonie allemande et un ennemi commun, le bolchevisme[117]. La Waffen-SS devait devenir l'éventuel noyau d'une armée européenne commune, où chaque État serait représenté par un contingent national[117]. Himmler lui-même, cependant, gave no concession to these views et maintenait sa vision pangermanique dans un discours prononcé en avril 1943 aux dirigeants des divisions SS LSAH, Das Reich et Totenkopf :

« Nous n'attendons pas de vous que vous renonciez à votre nation. […] Nous n'attendons pas de vous que vous deveniez allemand par opportunisme. Nous attendons de vous que vous subordonniez votre idéal national à un plus grand idéal racial et historique, au Reich germanique[117]. »

See also[modifier | modifier le code]

- New Order (Nazism), the overall Nazi conceptions of a post-WWII restructuring of the world.

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the envisioned Japanese equivalent to the Greater Germanic Reich and the New Order.

- Greater Italy, the Fascist Italian project for securing dominion over the Mediterranean area.

- Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany (see Planned future districts)

- Kleindeutschland and Grossdeutschland

- Racial policy of Nazi Germany

- Pan movements

- Axis victory in World War II

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

- This passage should in all likelihood be interpreted to mean "extending up to northern Italy", not that it would also include this region. There is no convincing evidence that Hitler intended to include any Italian provinces in the Nazi state before 1943, including South Tyrol.[33]

References[modifier | modifier le code]

- « Utopia: The 'Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation' », München - Berlin, Institut für Zeitgeschichte,

- Elvert 1999, p. 325.

- Speer 1970, p. 260.

- DHM - Mein Kampf

- Rich 1974, pp. 401-402.

- Strobl 2000, pp. 202-208.

- Williams 2005, p. 209.

- Bohn 1997, p. 7.

- Wright 1968, p. 115.

- Hitler 2000, p. 225.

- Housden 2000 , p. 163.

- Grafton et al. 2010, p. 363.

- Hitler, Pol Pot, and Hutu Power: Distinguishing Themes of Genocidal Ideology Professor Ben Kiernan, Holocaust and the United Nations Discussion Paper

- Hitler 2000, p. 307.

- Fest 1973, p. 685.

- Hitler 1927, p. 1.

- Fest 1973, p. 210.

- Fink 1985, pp. 27, 152.

- Hitler 2000, p. 306.

- On trouve le mot « germanique » dans le nom historique français (Saint-Empire romain de la Nation germanique), l'Allemagne n'existant pas encore en tant que telle à l'époque du Saint-Empire, mais bien deutscher (« allemand ») et non pas germanischer (« germanique ») dans le nom allemand (Heiliges römisches Reich deutscher Nation), d'où le nom ici adopté pour faire la correspondance complète aussi bien en français et en allemand entre le Saint-Empire et le projet.

- Hattstein 2006, p. 321.

- (en) Brigitte Hamann, Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship, New York, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 978-0-19-512537-5), ref = harv

- Haman 1999, p. 110

- Brockmann 2006, p. 179.

- Erreur de référence : Balise

<ref>incorrecte : aucun texte n’a été fourni pour les références nomméeswinkler - Goebbels, p. 51.

- Wright 1968, pp. 141-142.

- Rothwell 2005, p. 31.

- Lipgens 1985, p. 41.

- Speer 1970, pp. 147-148.

- Domarus 2007, p. 158.

- Speer 1970, pp. 115-116.

- Rich 1974, p. 318.

- Welch 1983, p. 145.

- Rich 1974, pp. 24-25, 140.

- See e.g. Warmbrunn 1963, pp. 91-93.

- Rich 1974, p. 140.

- Speer 1976, p. 47.

- Bramstedt 2003, pp. 92-93.

- Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2003, pp. 122-123.

- Morgan 2003, p. 182.

- Erreur de référence : Balise

<ref>incorrecte : aucun texte n’a été fourni pour les références nomméesjong1 - De Jong 1974, pp. 199-200.

- Adolf Hitler: Führer aller Germanen. Storm, 1944.

- Lipgens 1985, p. 101

- Rich 1974, p. 26.

- Hitler 2000, p. 400

- Rich 1974, p. 469, note 110.

- De Jong 1969, Vol. 1, p. 97.

- Fest 1973, p. 689.

- Waller 2002, p. 20.

- Kersten 1947, pp. 84-85.

- Louis de Jong, 1972, reprinted in German translation: H-H. Wilhelm and L. de Jong. Zwei Legenden aus dem dritten Reich : quellenkritische Studien, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1974, pp 79-142.

- Hitler (2000), 29th of May 1942.

- Gildea, Wieviorka & Warring 2006, p. 130.

- Hamacher, Hertz & Keenan 1989, p. 444.

- Rothwell 2005, p. 32.

- Janssens 2005, p. 205.

- Philip H. Buss, Andrew Mollo (1978). Hitler's Germanic legions: an illustrated history of the Western European Legions with the SS, 1941-1943. Macdonald and Jane's, p. 89 [1]

- Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 286

- Weinberg 2006, pp. 26-27.

- Weinberg 2005, pp. 26-27.

- Leitz 2000, p. 52.

- Ackermann 1970, p. 191.

- Kersten 1957, p. 143.

- Rich 1974, p. 500.

- The Goebbels diaries, 1942-1943, p.171.

- Griffiths 2004, pp. 180-181.

- Rich 1974, p. 401.

- Jarto Nieme et Jason Pipes, « Finnish Volunteers in the Wehrmacht in WWII », Feldgrau (consulté le )

- Boog 2001, p. 922.

- Kersten 1947, pp. 131, 247.

- Urner 2002, p. x.

- Halbrook 1998, pp. 24-25.

- Hitler 2000.

- Fink 1985, pp. 71-72.

- (en) Hans Rudolf Fuhrer, Spionage gegen die Schweiz, Huber, (ISBN 3274000035), p. 68

- Halbrook 1998, p. 151.

- Schöttler 2003, pp 83-131.

- Steininger 2003, p. 67.

- Rich 1974, p. 384.

- Rich 1974, p. 198.

- Zaloga 2007, p. 10.

- Petacco 2005, p. 50.

- Rich 1974, p. 317.

- Wedekind 2006, pp. 113, 122-123.

- Kersten 1947, p. 186.

- Rich 1974, pp. 320, 325. Quoting Goebbels:Whatever was once an Austrian possession we must get back into our own hands. The Italians by their infidelity and treachery have lost any claim to a national state of the modern type.

- Hitler 2000, p. 380.

- Kroener, Müller, Umbreit (2003), Germany and the Second World War: Volume V/II: Organization and Mobilization in the German Sphere of Power: Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942-1944/5, p. 79, (ISBN 0-19-820873-1)

- Wedekind 2003, Nationalsozialistische Besatzungs- und Annexionspolitik in Norditalien 1943 bis 1945, pp. 100-101

- Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 211.

- Ward 2008.

- Rich 1974, p. 398.

- Strobl 2000, pp. 36-60.

- Strobl 2000, p. 84.

- Strobl 2000, p. 85.

- Hitler 2003.

- Strobl 2000, p. 61.

- Rich 1974, p. 396.

- Nicosia 2000, p. 73.

- Nicosia 2000, p. 74.

- Hildebrand 1973, p. 99.

- Hildebrand 1973, p. 96.

- Hildebrand 1973, p. 105.

- Hildebrand 1973, pp. 100-105.

- Pinkus 2005, p. 259.

- Rich 1974, p. 421.

- Sanders 2005, p. xxiv.

- Sanders 2005, p. 188.

- Rich 1974, p. 397.

- Weinberg 2006, p. 35.

- Rich 1974, p. 331.

- Madajczyk.

- Poprzeczny 2004, p. 181.

- Nicholas 2006, pp. 330-331

- Stein 1984, pp. 145-148.

- Bibliography

- (de) Josef Ackermann, Heinrich Himmler als Ideologe, Musterschmidt,

- (de) Robert Bohn, Die deutsche Herrschaft in den "germanischen" Ländern 1940-1945, Steiner, (ISBN 3515070990, lire en ligne)

- (en) Horst Boog, Germany and the Second World War, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 0198228880)

- (en) E. K. Bramstedt, Dictatorship and Political Police: The Technique of Control by Fear, Routledge, (ISBN 0415175429)

- (en) Stephen Brockmann, Nuremberg: the imaginary capital, Camden House, (lire en ligne)

- (nl) Louis De Jong, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog: Voorspel, M. Nijhoff, (lire en ligne)

- (nl) Louis De Jong, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog: Maart '41 - Juli '42, M. Nijhoff,

- (en) Max Domarus, The essential Hitler: speeches and commentary, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc., (ISBN 9780865166653, lire en ligne)

- (de) Jürgen Elvert, Mitteleuropa!: deutsche Pläne zur europäischen Neuordnung (1918-1945), Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH, (ISBN 3515076417, lire en ligne)

- (en) Joachim C. Fest, Hitler, Verlagg Ulstein, (ISBN 0156027542)

- (de) Jürg Fink, Die Schweiz aus der Sicht des Dritten Reiches, 1933-1945, Schulthess, (ISBN 3725524300, lire en ligne)

- (en) Robert Gildea, Olivier Wieviorka et Anette Warring, Surviving Hitler and Mussolini: Daily Life in Occupied Europe, Berg Publishers, (ISBN 1845201817, lire en ligne)

- (en) Joseph Goebbels et Fred Taylor, The Goebbels diaries, 1939-1941, H. Hamilton, (ISBN 0241108934, lire en ligne)

- (en) Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most et Salvatore Settis, The Classical Tradition, Harvard University Press, (ISBN 0674035720, lire en ligne)

- (en) Tony Griffiths, Scandinavia, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, (ISBN 1850653178)

- (en) Stephen P. (1998). Halbrook, Target Switzerland: Swiss Armed Neutrality in World War II, Sarpedon, (ISBN 0306813254)

- (en) Werner Hamacher, Thomas Hertz et Anette Keenan, Responses: On Paul de Man's Wartime Journalism, University of Nebraska Press, (ISBN 9780803272439, lire en ligne)

- Markus Hattstein, « Holy Roman Empire, The », dans Cyprian Blamires et Paul Jackson, World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, (ISBN 1576079406, lire en ligne)

- (en) Klaus Hildebrand, The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich, University of California Press, (ISBN 0520025288)

- (en) Andreas Hillgruber et Henry Picker, Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier 1941–1942,

- (en) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Eher Verlag,

- (en) Adolf Hitler, Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944, 3rd, (ISBN 1929631057)

- (en) Adolf Hitler, Hitler's Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf, Enigma Books, (ISBN 1929631162, lire en ligne)

- (en) Martyn Housden, Hitler: study of a revolutionary?, Taylor & Francis, (ISBN 0415163595, lire en ligne)

- (nl) Jozef Janssens, Superhelden op perkament: middeleeuwse ridderromans in Europa, Amsterdam University Press, (ISBN 9053568220, lire en ligne)

- (en) Felix Kersten, The Kersten Memoirs, 1940-1945, Hutchinson,

- (en) Felix Kersten, The Memoirs of Doctor Felix Kersten, Doubleday & Company, (lire en ligne)

- (en) Jørgen Kieler, Resistance Fighter: A Personal History of the Danish Resistance Movement, 1940-1945, Gefen Publishing House, (ISBN 9652293970)

- (en) Bernhard Kroener, Rolf-Dieter Müller et Hans Umbreit, Germany and the Second World War: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942-1944/5, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 0198208731)

- (en) Christian Leitz, Nazi Germany and Neutral Europe During the Second World War, Manchester University Press, (ISBN 0719050693)

- (en) Walter Lipgens, Documents on the History of European Integration: Continental Plans for European Union 1939-1945, Walter de Gruyter, (ISBN 3110097249)

- Czeslaw Madajczyk, « Generalplan East: Hitler's Master Plan for Expansion », Polish Western Affairs, vol. III, no 2, (lire en ligne)

- (en) Philip Morgan, Fascism in Europe, 1919-1945, Routledge, (ISBN 0415169429)

- (en) Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web, Vintage Books, (ISBN 0-679-77663-X)

- (en) Francis R. Nicosia, The Third Reich and the Palestine Question, Transaction Publishers, (ISBN 076580624X)

- (en) Arrigo Petacco, A Tragedy Revealed: The Story of the Italian Population of Istria, Dalmatia, and Venezia Giulia, 1943-1956, University of Toronto Press, (ISBN 0802039219)

- (en) Oscar Pinkus, The War Aims and Strategies of Adolf Hitler, McFarland, (ISBN 0786420545)

- (en) Joseph Poprzeczny, Odilo Globocnik: Hitler's Man in the East, McFarland, (ISBN 9780786416257, lire en ligne)

- (en) Norman Rich, Hitler's War Aims: The Establishment of the New Order, W.W. Norton & Company, (ISBN 039333290X)

- (en) Victor Rothwell, War Aims in the Second World War: the War Aims of the Major Belligerents, Edinburgh University Press, (ISBN 0748615032, lire en ligne)

- (en) Paul Sanders, The British Channel Islands under German Occupation, 1940-1945, Paul Sanders, (ISBN 0953885836)

- (en) Alexander Sager et Heinrich August Winkler, Germany: The Long Road West. 1933-1990, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 0199265984)

- (de) Peter Schöttler, « Eine Art "Generalplan West": Die Stuckart-Denkschrift vom 14. Juni 1940 und die Planungen für eine neue deutsch-französische Grenze im Zweiten Weltkrieg », Sozial Geschichte, vol. 18, no 3, , p. 83–131

- (en) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich, Macmillan Company,

- (en) Albert Speer, Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Macmillan Company,

- (en) George H. Stein, The Waffen SS: Hitler's elite guard at war, 1939-1945, Cornell University Press, (ISBN 0801492750)

- (en) Bernd Stegemann et Detlef Vogel, Germany and the Second World War: The Mediterranean, South-East Europe, and North Africa, 1939-1941, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 0198228848)

- (en) Rolf Steininger, South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, Transaction Publishers, (ISBN 0765808005)

- (en) Gerwin Strobl, The Germanic Isle: Nazi Perceptions of Britain, Cambridge University Press, (ISBN 0521782651, lire en ligne)

- (en) Klaus Urner, Let's Swallow Switzerland! Hitler's Plans Against the Swiss Confederation, Lexington Books, (ISBN 0739102559, lire en ligne)

- (en) John H. Waller, The Devil's Doctor: Felix Kersten and the Secret Plot to Turn Himmler Against Hitler, Wiley, (ISBN 0471396729, lire en ligne)

- Ward, Vanessa, « Nationalist Uses of the Atlantis Myth in a Nordic Framework », Pseudoarchaeology Research Archive, (consulté le )

- (en) Werner Warmbrunn, The Dutch Under German Occupation, 1940-1945, Stanford University Press, (ISBN 0804701520)

- (en) Michael Wedekind, German Scholars and Ethnic Cleansing, 1919-1945, Berghahn Books, (ISBN 9781845450489), « The Sword of Science: German Scholars and National Socialist Annexation Policy in Slovenia and Northern Italy »

- (en) Gerhard L. Weinberg, Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders, Cambridge University Press, (ISBN 0521852544)

- (en) David Welch, Nazi Propaganda: The Power and the Limitations, Taylor & Francis, (ISBN 0389204005)

- (en) John Frank Williams, Corporal Hitler and the Great War 1914-1918: the List Regiment, Taylor & Francis, (ISBN 0415358558, lire en ligne)

- (en) Gordon Wright, The Ordeal of Total War: 1939-1945, Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated, (ISBN 061314080[à vérifier : ISBN invalide])

- (en) Steven J. Zaloga, The Atlantic Wall (1):France, Osprey Publishing, (ISBN 184603129X)

External links[modifier | modifier le code]

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Greater Germanic Reich » (voir la liste des auteurs).

Modèle:Nazism Category:Nazi Germany Category:Nazism Category:World War II Category:Pan movements