Utilisateur:Polidore/Brouillon

Les tapis d'Orient, qu'ils proviennent de l'Empire Ottoman, de l'Arménie, de l'Azerbaïdjan, du Levant, de l'Egypte mamelouke, ou encore d'Afrique du Nord, ont été des éléments décoratifs importants dans la peinture à partir du 14e siècle. Il subsiste plus de représentations de tapis d'Orient dans la peinture de la Renaissance que de tapis effectivement fabriqués avant le 17e siècle, ce qui rend l'étude de ces peintures essentielle pour écrire l'histoire de la fabrication de ces tapis. Ceux-ci ont souvent été intégrés à des images chrétiennes en tant que symboles de luxe oriental, et sont, au même titre que l'écriture pseudo-coufique, des exemples intéressants de l'intégration d'éléments orientaux dans la peinture de la Renaissance, et de l'influence islamique sur l'art chrétien.

Caractéristiques[modifier | modifier le code]

On sait que des tapis noués avec dessins géométriques ont été produits à partir du 13e siècle dans le Sultanat de Roum en Anatolie orientale, avec lequel Venise avait des relations commerciales depuis 1220.[1] Marco Polo, marchand et voyageur, mentionna que les tapis fabriqués à Konya étaient les meilleurs au monde. [1] Des tapis furent également fabriqués dans l'Espagne musulmane, par exemple celui représenté dans une fresque des années 1340 au Palais des Papes à Avignon.[2] La grande majorité des tapis représentés dans la peinture des 15e et 16e siècles sont, soit des productions de l'Empire ottoman, soit des copies européennes de ces modèles, fabriquées dans les Balkans, en Espagne ou ailleurs. En fait, il ne s'agissait pas des plus beaux tapis islamiques de cette période : les tapis de cour turcs de qualité exceptionnelle y sont peu nombreux. Les tapis persans, encore plus fins, n'apparurent pas avant la fin du 16e siècle ; ils devinrent de plus en plus populaires chez les plus riches au 17e siècle. Les tapis raffinés provenant des ateliers mamelouks en Egypte sont parfois vus, dans la peinture vénitienne notamment.[3]

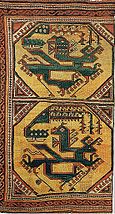

A droite : tapis "phénix-et-dragon", première moitié ou milieu du 15e siècle.[4]

L'une des premières utilisations d'un tapis d'orient dans une peinture européenne est le Saint Louis de Toulouse couronnant Robert d'Anjou, roi de Naples, peint par Simone Martini en 1316-1319 (Naples, musée Capodimonte).[5] La plupart des représentations européennes de tapis d'Orient sont extrêmement fidèles aux originaux, si on les compare aux quelques exemples encore existants de tapis de cette époque. La grande échelle des peintures permet également une représentation plus détaillée et précise que celle des miniatures perses ou turques. La plupart des tapis utilisent des motifs géométriques islamiques, même si les plus précoces utilisent également des motifs d'animaux comme le "phénix-et-dragon" d'origine chinoise, vu dans Le Mariage des enfants trouvés de Domenico di Bartolo (1440, Sienne, Hôpital Santa Maria della Scala). Ceux-ci avaient été stylisés et simplifiés en motifs quasi-géométriques lors de leur transmission au monde islamique.[6] Ce groupe, connu sous le nom de "tapis dragons", fut apparemment réalisé par des Arméniens en Asie mineure orientale ou dans le Caucase.[7] Ils disparurent des peintures vers la fin du 15e siècle. Seule une poignée de tapis à motifs d'animaux survit aujourd'hui, provenant principalement d'églises européennes, où leur rareté les a probablement préservés.[8]

Bien que les tapis soient représentés sur un sol public dans quelques exemples, l'emplacement de la plupart des tapis est réservé aux protagonistes principaux, très souvent sur un dais, ou devant un autel, ou encore sur des marches aux pieds de la Vierge Marie, ou de saints, ou de dirigeants, comme un tapis rouge actuel[10]. Ceci reflète probablement une utilisation royale : au Danemark, le tapis du couronnement, un tapis persan du 16e siècle est, encore aujourd'hui, placé sous le trône le jour du couronnement. Les tapis pendent également des balustrades ou des fenêtres pour les occasions festives, comme les processions représentées par Vittore Carpaccio ou Gentile Bellini (voir galerie)[11] ; dans L'Embarquement de sainte Ursule de Carpaccio, celle-ci s'avance sur un pont de bois orné de tapis[12].

Les tapis d'Orient étaient très souvent utilisés comme élément décoratif dans les scènes religieuses, en tant que symbole de luxe, statut et bon goût[13], bien qu'ils deviennent moins rares avec le temps, ce qui se voit dans les tableaux. Dans certains cas, comme chez Gentile Bellini, les tapis reflètent un intérêt précoce envers l'Orient, mais pour la plupart des peintres ils sont simplement le signe du prestige des tapis en Europe. Un exemple typique en est le tapis turc placé aux pieds de la Vierge Marie dans le retable de San Zeno, peint par Andrea Mantegna en 1456-1459 [14]. Dans les portraits ne représentant pas de personnes de familles royales, les tapis étaient plus souvent placés sur une table ou un meuble, notamment en Europe du Nord, bien que de petits tapis ne soient pas exceptionnels le long d'un lit, comme dans Les Epoux Arnolfini de 1434.[15] Des tapis sur des tables sont visibles particulièrement dans des peintures italiennes montrant l'Appel de saint Matthieu, concentré sur ses tâches de collecteur des impôts[16], et la vie de saint Eloi, qui était orfèvre.

Les tapis d'Orient utilisés dans les peintures de la Renaissance étaient d'origines diverses, indiquées en Italie par les noms qui leur étaient donnés : les cagiarini (tapis mamelouks d'Egypte), les damaschini (de la région de Damas), les barbareschi (d'Afrique du Nord), les rhodioti (probablement importés via Rome), les turcheschi (Empire ottoman) et les simiscasa (CIrcassiens ou Caucasiens).[17]

Certains des tapis représentés dans les peintures religieuses chréitennes sont des tapis de prière musulmans, avec des motifs tels que le mihrab ou la Kaaba (tapis de type "Bellini").[18] La représentation de tels tapis de prière disparaît après 1555, probablement suite à la reconnaissance de leur signification religieuse et de leur connection à l'Islam.[19]

La représentation de tapis d'Orient dans les peintures autres que les portraits a généralement reculé après les années 1540, en raison d'un goût moins prononcé pour la représentation très détaillée d'objets parmi les peintres[20], et à la volonté de situer les scènes religieuses dans des environnements classicisants.

Motifs de tapis nommés d'après des peintres[modifier | modifier le code]

When Western scholars explored the history of Islamic carpetmaking, several types of carpet pattern became conventionally called after the names of European painters who had used them, and these terms remain in use. The classification is mostly that of Kurt Erdmann, once Director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst (Berlin), and the leading carpet scholar of his day. Some of these types ceased to be produced several centuries ago, and the location of their production remains uncertain, so obvious alternative terms were not available. The classification ignores the border patterns, and distinguishes between the type, size and arrangement of gul, or larger motifs in the central field of the carpet. In addition to four types of Holbein carpets,[21] there are Bellini carpets, Crivellis, Memlings, and Lotto carpets.[22]

Bellini carpets[modifier | modifier le code]

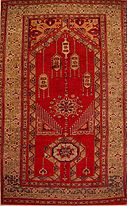

Right image: Re-entrant prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century.

Both Giovanni Bellini and his brother Gentile (who visited Istanbul in 1479) painted examples of these prayer-rugs with a single "re-entrant" or keyhole motif at the bottom of a larger figure traced in a thin border. At the top end the borders close diagonally to a point, from which hangs down a "lamp". The design had Islamic significance, and its function seems to have been recognised in Europe, as they were known in English as "musket" carpets, a corruption of "mosque".[23] In the Gentile Bellini seen at top the rug is the "right" way round; often this is not the case. Later Ushak prayer-rugs where both ends have the diagonal pointed inner border, as at the top only of Bellini rugs, are sometimes known as Tintoretto rugs, though this term is not as commonly used as the others mentioned here.[24]

Crivelli carpets[modifier | modifier le code]

Right image: "Crivelli" carpet, Anatolia, late 15th-early 16th century.

Right image: Qazakh carpet, Qazakh school,[27] late 14th to early 15th century, Azerbaijan Carpet Museum[27]

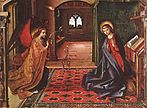

Carlo Crivelli twice painted what seems to be the same small rug, with the centre taken up with a complex sixteen-pointed star motif made up of several compartments in different colours, some containing highly stylised animal motifs. Comparable actual carpets are extremely rare, but there are two in Budapest.[28] The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius in the National Gallery, London (1486) shows the type hung over a balcony to the top left. These seem to be a transitional type between the early animal-pattern carpets and later purely geometrical designs, such as the Holbein types, perhaps reflecting increased Ottoman enforcement of Islamic aniconism.[29]

-

Carlo Crivelli's Virgin Mary Annunciate (detail), 1482.

-

Carlo Crivelli's detail of Almsgiving with Crivelli carpet in the Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486.

Memling carpets[modifier | modifier le code]

Right image: Konya 18th century carpet with Memling gul design.

These are named after Hans Memling, who painted what may have been Armenian carpets[réf. nécessaire] in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, and are characterised by several lines coming off the motifs that end in "hooks", by coiling in on themselves through two or three 90° turns.[31][32]

Holbein carpets[modifier | modifier le code]

Right image: Small-pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia, 16th century.

Erreur : La version française équivalente de {{Main}} est {{Article détaillé}}. These in fact are seen in paintings from many decades earlier than Holbein, and are sub-divided into four types (of which Holbein actually only painted two); they are the commonest designs of Anatolian carpet seen in Western Renaissance paintings, and continued to be produced for a long period. All are purely geometric and use a variety of arrangements of lozenges, crosses and octagonal motifs within the main field. The sub-divisions are between:[35]

- Type I: Small-pattern Holbein. The motifs are small, and usually of several different types that recur regularly - see the Somerset House group portrait below.[36]

- Type II: now more often called Lotto carpets - see below.

- Type III: Large-pattern Holbein. The motifs in the field inside the border are large squares filled with decoration, placed regularly, with narrow strips between them containing no "gul" motifs. The carpet in Holbein's The Ambassadors is of this type.[37]

- Type IV: Large-pattern Holbein. The square compartments have octagons or other "gul" motifs from the small-pattern types between them.[38]

-

Master of Saint Giles, Mass of Saint Giles, c. 1500, with a Type III Holbein carpet.

-

French ambassador to England Jean de Dinteville in "The Ambassadors", by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533. Holbein frequently used carpets in portraits, on tables for most sitters, but on the floor for Henry VIII. This is a "large-pattern Holbein", Type III.

-

Darmstadt Madonna by Hans Holbein the Younger, with donor portraits, on a Holbein Type III carpet. 1525–26 and 1528.

-

Portrait of Archbishop William Warham, with a large pattern Holbein Type IV carpet in the right corner, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1527).

Lotto carpets[modifier | modifier le code]

Right image: Western Anatolia knotted wool "Lotto carpet", 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Erreur : La version française équivalente de {{Main}} est {{Article détaillé}}. Previously known as Small-pattern Holbein Type II, but he never painted one, unlike Lorenzo Lotto, who did so several times, though he was not the first artist to show them. Lotto is also documented as owning a large carpet, though its pattern is unknown.

Though they look very different from Holbein Type I carpets, they are a development of the type, where the edges of the motifs, nearly always in yellow on a red ground, take off in rigid arabesques somewhat suggesting foliage, and terminating in branched palmettes. The type was common and long-lasting, and is also known as "Arabesque Ushak".[40]

Other examples[modifier | modifier le code]

Italy[modifier | modifier le code]

-

The Spanish painter Pedro Berruguete's Annunciation panel, late 15th century. The carpet may also be Spanish.

-

Oriental carpet in Piero della Francesca's The Brera Madonna 1460s.

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio's Madonna and Child enthroned with Saint, c. 1483, with a Holbein Type I.

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio's Madonna and Child enthroned between Angels and Saint c. 1486.

-

Oriental carpet in Tommaso di Piero's Sacra Conversazione, 1490-1500.

-

Carpets displayed over windows for a procession in Venice. Detail by Vittore Carpaccio, 1507

-

Giovanni Bellini's Naked Young Woman in Front of the Mirror, c. 1515.

-

Oriental carpet (a Star Ushak design) at the feet of the Doge in the 1534 Return of the Doge's Ring by Paris Bordone.

-

The Protonotary Giovanni Giuliano, North Italy 1530-40

Early Netherlandish and Northern Renaissance[modifier | modifier le code]

-

Jan van Eyck's Madonna with Canon Van der Paele (1434). Origin of carpet unknown, as no comparable carpets survive.[41] Possibly Egyptian.

-

Small bedside rug in Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (1434), which contains many elements that were extremely expensive at the time.

-

Hans Memling, but not a "Memling carpet".

-

Hans Memling The Virgin and Child with Angel Saint Georges and Donor 1470-1480.

-

Hans Holbein the Younger's Portrait of the merchant Georg Gisze, 1532.

England[modifier | modifier le code]

-

Elizabeth I of England c.1599, studio of Nicholas Hilliard

France[modifier | modifier le code]

-

"Hearing" from the tapestry set of The Lady and the Unicorn, c. 1500. There is a rug draped over the portative organ

17th century[modifier | modifier le code]

Carpets remained an important way of enlivening the background of full-length portraits throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, for example in the English portraits of William Larkin.[44] The finely-knotted silk carpets woven in the time of Shah Abbas I at Kashan and Isfahan are rarely represented in paintings, as they were doubtless very unusual in European homes;[45] however, A Lady playing the Theorbo. by Gerard Terborch (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.40.617) shows such a carpet laid upon the table on which the lady's cavalier is sitting.[46] Floral "Isfahan" carpets of the Herat type, on the other hand, were exported in great numbers to Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands, and are often represented in interiors painted by Velásquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, Vermeer, Terborch, de Hooch, Bol and Metsu, where the dates established for the paintings provide a yardstick for establishing the chronology of the designs.[47] Anthony van Dyck's royal and aristocratic subjects had mostly progressed to Persian carpets, but less wealthy sitters are still shown with the Turkish types; in the American colonies Isaac Royall and his family were painted by Robert Feke in 1741, posed round a table spread with a Bergama rug.[48] From the mid-century European direct trade with India brought Mughal versions of Persian patterns to Europe. Painters of the Dutch Golden Age showed their skill by depiction of light effects on table-carpets, like Vermeer in his Music Lesson (Royal Collection). By this date they have become common in the homes of the reasonably well-to-do, as is shown by historical documentation of inventories, and even appear in brothel scenes from the prosperous Netherlands.[49]

By the end of the century Oriental carpets had lost much of their status as prestige objects, and the grandest sitters for portraits were more likely to be shown on the high-quality Western carpets, like Savonneries, now being produced, whose less intricate patterns were also easier to depict in a painterly manner. A number of Orientalist European painters continued to accurately depict Oriental carpets, now usually in Oriental settings.

-

The Somerset House Conference 19 August 1604. The Spanish diplomats on the left, the English on the right. A late example of the "small-pattern Holbein", Type I. (painting)

-

Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset by William Larkin, 1613, standing on a Lotto carpet. Most of Larkin's full-length subjects stand on carpets.

-

Nicolas Regnier's Fortune-teller, 1626, Louvre.

-

Nicolas Tournier's Concert 1630-1635.

-

Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, with his Family, by Anthony van Dyck, whose sitters had mostly moved on to Persian carpets.

-

Vermeer's Music Lesson uses semi-transparent glazes to create the effect of light on a pile carpet.

-

Vermeer's The Procuress; carpets are now shown in brothel scenes

See also[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

- Mack, p.74

- King & Sylvester, 10-11

- King & Sylvester, 17

- Mack, p.75

- Mack, p.74-75. Image

- Mack, p.75. King & Sylvester, pp. 13, and 49-50.

- First encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936 p.108

- King & Sylvester, pp. 49-50. Le tapis de Marby, l'un des plus beaux exemples, est conservé en Suède.

- King & Sylvester, p.15

- Mack, p.76

- King & Sylvester, p. 14

- Carpaccio image

- Mack, p.73-93

- Mack, p.67

- King & Sylvester, p. 20

- King & Sylvester, 14

- Mack, p.77

- Mack, p.84. King & Sylvester, p. 58.

- Mack, p.85.

- Mack, p.90

- Old Turkish carpets website

- King & Sylvester

- King and Sylvester, pp. 14-16, 56, 58.

- King & Sylvester, 78

- (en) Роя Тагиева, Азербайджанский ковёр, «Элм», , p. 9 :

« “Проникнув в быт европейцев, азербайджанское ковры попали на полотна многих европейских художников XV-XVI вв. Так, ковер “Мугань” Гарабахской группы мы видим на картинах Ганса Мемлинга (XV в.) -”Мария с младенцем”, ” Натюрморт с кувшином с цветами” (1485) и “Портрет молодого человека”. Азербайджанские ковры Гянджа-Казахского типа запечатлены на картине немецкого художника Ганса Гольбейна (XVI в.) - “Послы”, венецианского художника Карло Кривелло (XV в.) - “Возвещение” и другого итальянского художника Антонелли де Мессина (XV в.) - “святой Cебастьян”. Азербайджанские ковры мы видим на фреске собора Санта Мария в городе Сиене (“Свадьба Финдлинга”) художника Доменико де Бартоло, на картине Доменико Мороне - “Рождение святого Фомы”, на гобелене “Дама с единорогом” (XV в.) из Франции и на многих других картинах европейских художников.» »

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijani carpets, Baku, 2012, page 10

XV-XVI əsrlərdə avropalıların məişətinə nüfuz edən Azərbaycan xalçaları bir çox Avropa rəssamlarının tablolarında əks olunmuşdur. Misal üçün, Qarabağın “Muğan” xalçasını Hans Memlinqin (XV ə.) “Məryəm körpəsi ilə” və “Bir gəncin portreti” tablolarında görürük. Azərbaycan xalçası venesiyalı rəssam Karlo Krivellonun (XV ə.) “Müjdə” tablosunda və digər italyan rəssamı Antonello de Messinanın (XV əsr) “Müqəddəs Sebastyan” tablosunda əks etdirilib. Azərbaycan xalçalarının təsvirinə rəssam Domeniko de Bartolonun Siyena şəhərində Santa-Mariya kilsəsindəki (“Findlinqin toyu”) freskasında, Domeniko Moronenin “Müqəddəs Fomanın doğulması” rəsmində, Fransadakı “Gərgədanla xanım” (XV ə.) şpalerasında (tapissetrie), Avropa və rus rəssamlarının bir çox digər əsərlərində də təsadüf edilir.

- Лятиф Керимов. Азербайджанский ковёр. Том III. VI. Казахская школа. Б.: «Гянджлик», 1983, рис.56

- One shown here, about a third of the way down the page.

- King & Sylvester, pp. 14, 26, 57-58. Campbell, p. 189.National Gallery zoomable image. There is a different type of carpet hung from the Virgin's house, at top center-right.

- King and Sylvester, p. 57

- Todd Richardson, Plague, Weather, and Wool, AuthorHouse, 2009, p.182(344), (ISBN 1-4389-5187-6 et 978-1-4389-5187-4)

- King and Sylvester, p. 57.

- Erreur de référence : Balise

<ref>incorrecte : aucun texte n’a été fourni pour les références nomméesReferenceA - Лятиф Керимов. Азербайджанский ковёр. Том III. VI. Карабахская школа. Б) Джебраилская группа. Б.: «Гянджлик», 1983, рис.122

- King & Sylvester, pp. 26-27, 52-57. Campbell, p. 189.

- Old Ottoman carpets, see also last note.

- Old Ottoman carpets, Large-pattern Type III Holbein Carpets. See also note to the last paragraph.

- Old Ottoman carpets, Large-pattern Type IV Holbein Carpets. See also note to the last paragraph.

- King and Sylvester, p. 17.

- Cambell, p. 189. Old Ottoman carpets. Type II Holbein or "Lotto" Carpets. King and Sylvester, pp. 16, 67-70.

- King and Sylvester, 20

- Historic floors by Jane Fawcett p.156

- Historic floors by Jane Fawcett p.157

- King & Sylvester, 19

- Examples in Polish collections led to their being miscalled "Polish carpets" in the 19th century, a misnomer that has stuck: "representations of 'Polish' silk rugs in paintings are rare" report Dimand and Mailey 1973, p.59.

- Maurice Dimand and Jean Mailey, Oriental Rugs in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 60, fig.83.

- Dimand and Mailey 1973, p 67, illustrating floral Herat rugs in A Visit to the Nursery by Gabriel Metsu (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.20), p. 67,fig. 94; Portrait of Omer Talon, by Philippe de Champaigne, 1649 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, p.70, fig. 98); Woman with a Water Jug, by Jan Vermeer (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 89.15.21, p.71, fig. 101

- In the collection of Harvard University Law School; illustrated in Dimand and Mailey 1973, p.193, fig. 178. An earlier Bergama rug appears in the portrait of Abraham Grapheus by Cornelis de Vos, in Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp (noted by Dimand and Maily).

- King & Sylvester, pp. 22-23

References[modifier | modifier le code]

- Campbell, Gordon. The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Volume 1, "Carpet, S 2; History(pp. 187–193), Oxford University Press US, 2006, (ISBN 0-19-518948-5 et 978-0-19-518948-3) Google books

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001 (ISBN 0-520-22131-1)

- King, Donald and Sylvester, David eds. The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century, Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1983, (ISBN 0-7287-0362-9)

External links[modifier | modifier le code]

- The Carpet Index: The Oriental Carpet in Early Renaissance Paintings

- Carpets in Western Europe During the Renaissance

Further reading[modifier | modifier le code]

- Brancati, Luca E., 'Figurative Evidence for the Philadelphia Blue-Ground SPH and an Art Historical Case Study: Gaudenzio Ferrari and Sperindio Cagnoli', Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies Vol. V part 1 (1999) 23-29.

- Mills, John, Carpets in Pictures, The National Gallery, London, 1976. Revised and expanded edition, published as Carpets in Paintings, 1983.

- Mills, John, 'Early animal carpets in western paintings - a review', HALI. The International Journal of Oriental Carpets and Textiles, Vol.1 no. 3 (1978), 234-43.

- Mills, John, 'Small-pattern Holbein carpets in western paintings', HALI, Vol. 1 no. 4 (1978), 326-34; 'Three further examples', HALI, Vol. 3 no. 3 (1981), 217.

- Mills, John, '"Lotto" carpets in western paintings', HALI, Vol. 3 no. 4 (1981), 278-89.

- Mills, John, 'East Mediterranean carpets in western paintings', HALI, Vol. 4 no.1 (1981), 53-5.

- Mills, John, 'Near Eastern Carpets in Italian Paintings' in Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies, Vol. II (1986), 109-21.

- Mills, John, 'The 'Bellini', 'Keyhole', or 'Re-entrant' rugs', HALI, Issue 58 (1991), 86-103, 127-8.

- Mills, John, 'The animal rugs revisited', Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies Vol. VI (2001), 46-51.

- Rocella, Valentina, 'Large-Pattern Holbein Carpets in Italian Paintings', Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies Vol. VI (2001), 68-73.

![Jan van Eyck's Madonna with Canon Van der Paele (1434). Origin of carpet unknown, as no comparable carpets survive.[41] Possibly Egyptian.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Jan_Van_Eyck_La_Madone_au_Chanoine_Van_der_Paele_1434.jpg/147px-Jan_Van_Eyck_La_Madone_au_Chanoine_Van_der_Paele_1434.jpg)

![Henry VIII standing on a star Ushak carpet, Hans Holbein the Younger c.1530.[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/83px-After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![Edward VI standing on a Holbein carpet, c.1547.[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Edward_VI_swagger.jpg/76px-Edward_VI_swagger.jpg)