Utilisateur:Utma Falos/Brouillon3

Le comportement du chien représente l'ensemble des actions (ou inactions) effectuées par le chien domestique (individuellement ou en groupe) en réponse à des stimuli intérieurs et/ou extérieurs[1]. En tant que plus ancienne espèce animale domestiquée par l'homme (les estimations de sa date d'apparition varient de -9 000 à -30 000 ans av. J.-C.), le comportement des chiens a inévitablement été façonné par des millénaires de contact avec les humains. Le résultat de cette évolution physique et sociale est que les chiens ont acquis, plus que tout autre espèce animale, la capacité de comprendre et de communiquer avec l'homme, et d'harmoniser leur comportement avec le nôtre de manière unique[2]. Les biologistes comportementalistes ont découvert une surprenante quantité de capacités cognitives et sociales chez le chien domestique. Capacités qu'on ne retrouve ni chez les autres espèces de canidés les plus proches du chien ni chez les grands singes (chimpanzé, gorille, orang-outan). Ces compétences propres au chien s'apparenteraient plutôt aux capacités cognitives et sociales de l'enfant humain[3].

Évolution - Domestication - Coévolution avec l'homme[modifier | modifier le code]

Les origines du chien domestique (Canis lupus familiaris) sont encore disputées. Les séquençages complets des génomes indiqueraient que le chien, le loup gris et le loup de Taïmyr (désormais éteint) ont divergé en même temps il y a entre 27 000 et 40 000 ans[4]. La manière dont les chiens ont été domestiqués n'est pas connue avec certitude, les deux hypothèses principales étant l'auto-domestication et la domestication humaine. Il existe des signes d'une véritable coévolution homme-chien.

Intelligence[modifier | modifier le code]

L'intelligence du chien est définie comme sa faculté à recevoir des informations et à les retenir en vue de les utiliser pour résoudre des problèmes futurs. On a pu montrer que les chiens étaient capables d'apprentissage par inférence. Une étude avec un border collie nommé Rico a montré qu'il connaissait les noms de plus de 200 différents objets[5]. Il déduisait le nom de nouveaux objets par une méthode d'exclusion et était capable de s'en souvenir encore quatre semaines après. Les chiens ont une très bonne mémoire. Ils sont capable de lire et de réagir de manière appropriée aux signes corporels humains tels que faire des gestes ou montrer du doigt, et de comprendre des ordres vocaux. Entraînés à résoudre un problème de manipulation simple, les chiens se tournent vers les humains lorsqu'ils sont confrontés à une version insoluble du même problème, alors que les loups apprivoisés ne le font pas. En se livrant à la duperie, les chiens font également montre de théorie de l'esprit[citation nécessaire].

Sens[modifier | modifier le code]

Les sens du chien incluent l'odorat, la vision, l’ouïe, le goût et le toucher.

Odorat[modifier | modifier le code]

Alors que le cerveau humain est dominé par un grand cortex visuel, le cerveau du chien est dominé par son cortex olfactif. Le bulbe olfactif du chien est environ quarante fois plus gros que celui de l'homme (relativement à la taille de leurs cerveaux respectifs), et comporte généralement entre 125 et 200 millions de récepteurs olfactifs. Le chien de Saint-Hubert ou bloodhound est le champion de l'olfaction avec ses 300 millions de récepteurs olfactifs[6].

Voir également la section Odeurs et socialité.

Vision[modifier | modifier le code]

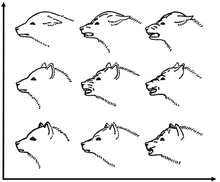

Comme la plupart des mammifères, les chiens ont seulement deux types de cônes photorécepteurs, ce qui fait d'eux des dichromates (ils ne voient que deux couleurs)[7],[8],[9],[10]. Leurs cônes photorécepteurs ont un maximum de sensibilité entre 429 nm et 555 nm. Des études comportementales ont pu mettre en évidence que le monde colorimétrique des chiens est composé de jaunes, de bleus et de gris[10], et qu'ils ont des difficultés à différencier le rouge du vert, comme les daltoniens deutéranopes humains. Quand un humain perçoit un objet comme rouge, cet objet apparait jaune au chien, et la perception humaine du vert correspond au blanc chez le chien. La « région blanche » (le point neutre) de la vision canine se situe aux alentours de 480 nm, une partie du spectre lumineux qui apparaitrait bleue-verte à un œil humain. Pour le chien, toute couleur correspondant à une longueur d'onde supérieure au point neutre ne peut pas être distinguée d'une autre et apparaît comme jaune[10].

Le système oculaire du chien s'est adapté au cours de son évolution pour maximiser l'efficacité de la chasse[7]. Alors que son acuité visuelle est faible (celle d'un caniche a été estimée à 20/75 sur le tableau de Snellen)[7], sa discrimination des objets en mouvement est excellente. On a pu montrer que les chiens étaient capable de différencier des humains (par exemple en identifiant leur maître) jusqu'à des distances de 800 à 900 mètres. Toutefois cette distance diminue à 500-600 mètres si les sujets restent immobiles[7].

Ouïe[modifier | modifier le code]

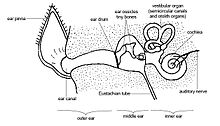

Les fréquences audibles par le chien se situent dans une gamme comprise entre 40 et 60 000 Hz[11], dépassant nettement les limites supérieures de l'oreille humaine (20 à 20 000 Hz)[9],[11],[12]. De plus, certains chiens ont les oreilles mobiles, ce qui leur permet, à la manière des chats, de les orienter rapidement vers la source précise d'un son[13]. Plus de dix-huit muscles permettent à un chien de faire pivoter, d'incliner, de lever ou baisser ses oreilles. Les oreilles sont également utilisées dans l'expression faciale et la communication des émotions. Un chien peut localiser la source d'un son bien plus rapidement qu'un humain et le percevoir jusqu'à une distance quatre fois plus grande[13].

Les chiens aux oreilles tombantes ont de ce fait des capacités auditives réduites par rapport à leurs congénères à oreilles droites. Historiquement, les éleveurs ont sans doute utilisé le caractère « oreilles tombantes », pourtant semi-handicapant, pour obliger les individus qui en étaient dotés à mieux utiliser leur odorat[citation nécessaire]. Aujourd'hui tous les chiens utilisés pour leur flair, comme les limiers, portent des oreilles tombantes.

Comportement de communication[modifier | modifier le code]

Le comportement de communication regroupe les sujets suivants : comment les chiens se parlent entre eux, comment ils comprennent les messages que les humains leur envoient, et comment les humains peuvent traduire les idées que les chiens essaient de leur transmettre[14]. Le chien peut communiquer à l'aide du regard, des expressions faciales, de la vocalisation, des expressions corporelles (incluant les mouvement du corps et des membres) et par le sens gustatif (odeurs, phéromones, goût). Les humains communiquent avec les chiens en utilisant vocalisation, signes de la main et posture corporelle.

Comportement social[modifier | modifier le code]

Le jeu[modifier | modifier le code]

De chien à chien[modifier | modifier le code]

Le jeu entre chiens comprend plusieurs comportements que l'on rencontre également dans les combats réels, comme les grondements et les morsures. C'est pourquoi il est très important pour les chiens de placer ces comportements dans le contexte du jeu, et non de celui de l'agression. Les chiens signalent leur volonté de jouer à l'aide de plusieurs comportements et postures invitant les autres à pourchasser l'initiateur. Des signaux similaires sont envoyés régulièrement durant le jeu pour maintenir le contexte de ces activités potentiellement agressives[15].

Depuis leur plus jeune âge, les chiens jouent les uns avec les autres. Le jeu entre chiens est principalement constitué de simulacres de combats. On pense que ce comportement, courant chez les chiots, constitue un entraînement important pour leur vie future. Le jeu entre chiots n'est pas forcément symétrique entre les individus pour ce qui concerne la distribution des rôles de domination et de soumission. Les chiens ayants les plus fortes fréquences de comportement dominant à l'âge adulte (comme le fait de pourchasser les autres ou de les forcer à se coucher au sol) sont également ceux qui avaient les plus grandes fréquences de jeu lorsqu'ils étaient chiots. Cela pourrait signifier que la victoire durant le jeu devient plus importante à la maturité[16].

De chien à humain[modifier | modifier le code]

La motivation qu'a un chien pour jouer avec un humain est différente de celle qu'il a pour jouer avec un autre chien. Les chiens qui sont promenés ensemble, ayant des opportunités pour jouer les uns avec les autres, jouent avec leurs maîtres à la même fréquence que les chiens promenés seuls. Les chiens habitant une cellule familiale comportant deux chiens ou plus jouent plus souvent avec leurs maîtres que les chiens vivants seuls, ce qui semblerait indiquer que la motivation du jeu entre chiens ne se substitue pas à la motivation du jeu avec les humains[17].

C'est une erreur courante de penser que le gain ou la perte d'un jeu comme le « tir à la corde » ou le « chahut » peut influencer la relation de dominance-soumission d'un chien envers les humains. La manière dont les chiens jouent indique plutôt leur tempérament et le type de relations qu'ils entretiennent avec leurs maîtres. Les chiens jouant au « chahut » sont en général plus souples et soumis et font preuve d'une moindre anxiété à la séparation que les chiens jouant à d'autres types de jeux, et les chiens jouant au « tir à la corde » et à « rapporte ! » sont en général plus confiants. Les chiens étant les initiateurs majoritaires des jeux sont en général les chiens les moins soumis et les plus susceptibles de se montrer agressifs[18].

Jouer avec les humains influence les niveaux de cortisol chez le chien. Dans une étude, on a mesuré les taux de cortisol de chiens policiers et de chiens douaniers après qu'ils aient joué avec leur maître. La concentration de cortisol a augmenté chez les chiens policiers, alors qu'elle a diminué chez les chiens douaniers. Les chercheurs avaient noté que pendant les sessions de jeu, les officiers de police disciplinaient et punissaient leurs chiens, alors que les gardes-frontières jouaient réellement avec eux, ayant des contacts physiques et des comportements d'affection. Les chercheurs ajoutent que plusieurs études ont pu montrer que les comportements associés à la maîtrise, à l'autorité et à l'agression augmentent les taux de cortisol chez le chien, alors que les comportements associés au jeu et à l'affection les diminuent[19].

Empathie[modifier | modifier le code]

En 2012, une étude à montré que les chiens se tournaient plus souvent vers leur maître (ou vers un étranger) lorsque la personne faisait semblant de pleurer, plutôt que lorsque la personne parlait. Quand un étranger faisait semblant de pleurer, les chiens, plutôt que de se diriger vers leur zone de confort naturelle, leur maître, s'approchaient de l'étranger, le sentaient, le touchaient de la truffe et le léchaient. Ce modèle de comportement est cohérent avec l'expression d'un sentiment d'empathie[20].

Une autre étude a pu mettre en évidence qu'un tiers des chiens souffraient d'anxiété quand ils étaient séparés des autres[21].

Personnalité[modifier | modifier le code]

Le terme « personnalité » est généralement utilisé dans le cadre de recherches sur l'humain, tandis que le terme « tempérament » est plutôt utilisé dans le cadre de recherches sur les animaux[22]. Toutefois, ces deux termes ont été utilisés de manière interchangeable dans la littérature consacrée, ou bien seulement dans le but de différencier formellement hommes et animaux afin d'éviter tout anthropomorphisme[23].

La personnalité peut être définie par « un ensemble de comportements qui demeurent constants au cours du temps et suivant les différents contextes »[24]. La personnalité humaine est souvent étudiée via des modèles qui la découpent en grands traits de caractères comportant de larges dimensions de personnalités. Par exemple, le modèle le plus couramment utilisé est celui des Big Five, c'est également le modèle le plus largement étudié. Il se compose de cinq dimensions : ouverture, conscienciosité, extraversion, agréabilité et neuroticisme[25]. Les études portant sur les personnalités canines ont également essayé d'identifier de larges traits de personnalité restants stables au cours du temps[23],[24]. On a pu récemment montrer que les personnalités canines demeurent relativement constantes au cours du temps[26],[27].

Il existe différentes méthodes permettant d'évaluer la personnalité d'un chien :

- Évaluation individuelle : un soigneur ou un expert canin familier du chien à évaluer remplit un questionnaire concernant la fréquence avec laquelle le chien adopte un certain type de comportement[28]. Exemple (anglais) : the Canine Behavioural Assessment and Research Questionnaire.

- Batterie de tests : le chien est soumis à une série de tests et ses réactions sont évaluées sur une échelle comportementale. Par exemple, on présente au chien un familier puis un inconnu, dans le but de mesurer sa sociabilité et son agressivité[29].

- Test observationnel : le comportement du chien est évalué dans un environnement sélectionné, mais pas contrôlé. Un observateur étudie les réactions du chien au stimuli se produisant naturellement. Par exemple, une promenade au supermarché permet d'observer le chien dans un type de conditions variées (foule, bruit, etc.)[30].

Plusieurs traits de personnalité ont été potentiellement identifiés chez les chiens, comme par exemple « espièglerie », « curiosité et intrépidité », « prédisposition à la chasse », « sociabilité/agressivité » et « timidité/hardiesse »[31],[32]. Une méta-analyse regroupant 51 études publiées dans des revues à comité de lecture a identifié sept dimensions dans la personnalité canine[23] :

- Réactivité (approche ou évitement d'objets inconnus, activité accrue dans les situations nouvelles)

- Crainte (tremblements, évitement de situations nouvelles)

- Activité

- Sociabilité (initiateur d'interactions amicales avec des humains et avec d'autres chiens)

- Disposition à l'entraînement (travail avec des humains, apprentissage rapide)

- Soumission

- Agression

La race du chien joue un rôle important dans les dimensions de personnalité canines[33],[34], alors que les effets de l'âge et du sexe n'ont pas pu être clairement déterminés[24]. Ces modèles de personnalités canines peuvent être utilisés pour tout une gamme de tâches, comme par exemple trouver des familles appropriées pour accueillir des chiens abandonnés, ou encore aider à la sélection d'individus reproducteurs[35],[36],[37].

Domination[modifier | modifier le code]

Le terme « domination » est employé pour décrire les relations sociales entre deux individus. Pour les éthologues, la domination se définit comme « un motif répété d'interactions agressives entre deux individus, caractérisé par un résultat constamment en faveur du même membre du duo, et par une capitulation par défaut de son adversaire plutôt qu'une escalade dans l'agressivité. Le vainqueur a le statut de dominant et le vaincu celui de soumis »[38]. Une autre définition pourrait affirmer qu'un animal dominant a un accès privilégié aux ressources et à la reproduction[38]. La domination est un attribut relatif et non absolu ; il n'y a pas de raison de penser qu'un individu de rang supérieur dans un groupe conserverait son statut s'il était déplacé dans un autre groupe. Il n'y a pas non plus de preuve formelle que la dominance soit un caractère durable tout au long d'une vie. Les schémas de comportement caractérisant la domination (comme par exemple grognements, morsures simulées, fixer dans les yeux, se tenir debout au dessus, chasser, aboyer sur) et la soumission (évitement, léchage, bâillements, se coucher au sol, prendre la fuite) peuvent s'inverser[39].

Un test sûr permettant de déterminer quel chien est dominant dans un groupe consiste à répondre aux questions suivantes : quand un inconnu arrive à la maison, quel chien commence à aboyer le premier ? S'ils aboient en même temps, lequel aboie le plus fort ou le plus longtemps ? Quel chien lèche le plus souvent le museau des autres ? Si les chiens mangent au même endroit et au même moment, quel chien commence à manger le premier ou bien mange la part des autres ? Lorsque les chiens se battent, lequel gagne en général ?[40]

Il semble que les chiens domestiques accordent peu d'importance aux tailles relatives, en dépit de la large différence entre les individus les plus petits et les plus grands. Par exemple, la taille ne permet pas de faire une prédiction sur l'issue d'une rencontre lorsque les chiens sont en promenade avec leur maître. La taille n'est pas non plus corrélée avec le fait que les mâles soient castrés ou non[41]. Par conséquent, beaucoup de chiens semblent ne pas prêter attention aux capacités réelles de combat de leur opposant, sans doute en laissant les différences de motivation (la valeur que le chien attache à la ressource convoitée) et de perceptions de motivation (interprétation du comportement de l'autre chien pour sonder sa volonté de combattre) jouer un plus grand rôle[39].

Lorsque deux chiens se contestent pour la première fois la possession d'une ressource hautement convoitée, si l'un des deux est dans un état d'excitation émotionnelle, ou s'il ressent une souffrance, ou si ses réactions sont influencées par un récent changement endocrinien, ou motivées par un état comme la faim, alors l'issue de la rencontre peut se révéler différente de celle qui serait advenue sans la présence de ces facteurs. De même, le seuil de déclenchement de l'agression peut être influencé par toute une gamme de facteurs physiologiques, et, dans certains cas, être précipité à cause de troubles pathologiques. Par conséquent, les facteurs contextuels et physiologiques présents au moment de la première rencontre entre deux chiens peuvent influer considérablement la nature de leur relation sur le long terme. La complexité des facteurs intervenant dans ce type d'apprentissage indique que les chiens pourraient développer des « prévisions » sur les réactions probables d'un autre individu dans une série de situations différentes. Les chiots apprennent très tôt à ne pas défier leurs aînés, et ce respect peut les accompagner jusqu'à l'âge adulte. Quand deux individus adultes se rencontrent pour la première fois, ils n'ont pas encore appris à interpréter le comportement de l'autre, et donc se montrent en général anxieux et vigilants lors de cette rencontre initiale (souvent caractérisée par des postures corporelles tendues et des mouvements brusques), jusqu'à ce qu'ils se sentent capables de prédire les réactions de l'autre individu. Le résultat de ces interactions précoces entre adultes sera influencé par les facteurs spécifiques présents au moment de la rencontre initiale. De même que les facteurs contextuels et physiologiques, les expériences précédentes de chacun des membres du duo influeront sur leur comportement futur[39].

Odeurs et socialité[modifier | modifier le code]

Le sens olfactif du chien est 40 fois plus développé que celui de l'homme. Au début de leur vie, les chiots disposent uniquement du sens de l'odorat et de celui du toucher[14]:247. Les odeurs spécifiques que les chiens utilisent pour communiquer s'appellent les phéromones. Différentes hormones sont secrétées lorsque le chien est fâché, craintif ou confiant, et certaines signatures chimiques permettent d'identifier le sexe et l'âge de l'individu, et, s'il s'agit d'une femelle, d'identifier si elle est dans son cycle œstral (« en chaleur »), si elle est enceinte, ou si elle vient de mettre bas. Une grande partie de ces phéromones chimiques se retrouvent dissoutes dans l'urine du chien. Lorsqu'un chien renifle l'endroit où un autre a uriné, il se procure ainsi un grand nombre d'informations sur cet individu[14]:250. Les chiens mâles préfèrent « marquer » les surfaces verticales, et le plus haut possible car plus la marque est haute et plus l'odeur portera loin dans l'air[14]:251.

The height of the marking tells other dogs about the size of the dog, as among canines size is an important factor in dominance.

Les chiens (et les loups) n'utilisent pas seulement leur urine mais également leurs fèces pour marquer leur territoire. Les glandes anales des canidés produisent une signature particulière à chaque dépôt fécal qui identifie son auteur ainsi que l'endroit du dépôt. Les chiens sont très attentifs à ces marquages de territoire, et s'engagent dans ce qui pourrait sembler à un humain un rituel complexe et inutile avant de déféquer. La plupart des chiens commencent par une intense période de reniflage, peut-être pour déterminer la frontière exacte séparant leur territoire de celui d'un autre chien. Parfois l'endroit est choisi pour sa hauteur relative, comme sur une grosse pierre ou une branche tombée au sol, ce qui facilite la dispersion des odeurs. Gratter le sol après avoir déféqué est un signe visuel pointant vers la marque laissée. L'état de fraicheur de l'odeur donne au visiteur une idée du statut courant du territoire correspondant, par la fréquence des marques et le moment approximatif de la dernière marque. Les territoires disputés, ou utilisés par différents animaux à des moments différents, font l'objet de véritables « batailles » de marquage, où chaque marque laissée est rapidement masquée par celle d'un autre concurrent[14]:252.

Chiens sauvages[modifier | modifier le code]

Les chiens sauvages sont des chiens vivant à l'état sauvage, c'est-à-dire sans nourriture ni abri intentionnellement apportés par des humains, et montrant une disposition forte et continue à éviter tout contact direct avec notre espèce[42]. Dans les pays en développement, les chiens de compagnie sont rares, alors que les chiens de communauté, les chiens de village, et les chiens sauvages sont nombreux[43]. La distinction entre chien sauvage, chien errant et chien fugueur ou abandonné n'est parfois qu'une question de degré, et un individu peut évoluer d'un statut à l'autre au cours de sa vie. Dans certains cas, rares mais déjà observés, des chiens qui n'étaient pas nés sauvages mais vivaient avec un groupe de chiens sauvages ont pu être réhabilités à la vie domestique avec un maître. Un chien peut devenir errant s'il échappe au contrôle des humains, suite par exemple à un abandon, ou bien s'il est né d'une mère elle-même errante. Un chien errant peut devenir sauvage s'il est forcé à fuir l'environnement des humains, ou bien s'il est socialement accepté par un groupe de chiens sauvages. La féralisation (le processus inverse de la domestication) est le plus souvent la conséquence d'une réponse de peur à l'égard des humains[42].

Les groupes de chiens errant ne sont pas durables reproductivement parlant, car il subissent un énorme taux de mortalité juvénile. Il dépendent indirectement des humains pour leur nourriture, leur territoire et la fourniture de nouveaux individus intégrables au groupe[42].

Voir également la section Comportement comparé aux autres canidés.

Other behavior[modifier | modifier le code]

Dogs have a general behavioral trait of strongly preferring novelty ("neophillia") compared to familiarity.[44] The average sleep time of a dog in captivity in a 24-hour period is 10.1 hours.[45]

Comportement de reproduction[modifier | modifier le code]

Cycle œstral et accouplement[modifier | modifier le code]

Bien que les chiots ne soient pas pressés de procréer, certains mâles se lancent dans des jeux sexuels (monter sur le partenaire) dès l'âge de 5 semaines.

Les chiens atteignent leur maturité sexuelle dès leur première année, remarquablement tôt comparativement aux loups qui doivent attendre l'âge de 2 ans. Les chiennes ont leur premières « chaleurs » (cycle œstral) entre 6 et 12 mois. Les petits chiens ont en général une maturité sexuelle plus précoce, celle des grands chiens est plus tardive.

Dog bitches have an estrous cycle that is nonseasonal and monestrus, i.e. there is only one estrus per estrous cycle. The interval between one estrus and another is, on average, seven months, however, this may range between 4 to 12 months. This interestrous period is not influenced by the photoperiod or pregnancy. The average duration of estrus is 9 days with spontaneous ovulation usually about 3 days after the onset of estrus.[46]

For several days before estrus, a phase called proestrus, the bitch may show greater interest in male dogs and "flirt" with them (proceptive behavior). There is progressive vulval swelling and some bleeding. If males try to mount a bitch during proestrus, she may avoid mating by sitting down or turning round and growling or snapping.

Estrous behavior in the bitch is usually indicated by her standing still with the tail held up, or to the side of the perineum, when the male sniffs the vulva and attempts to mount. This tail position is sometimes called “flagging”. The bitch may also turn, presenting the vulva to the male.[46]

The male dog mounts the female and is able to achieve intromission with a non-erect penis, which contains a bone called the os penis. The dog's penis enlarges inside the vagina, thereby preventing its withdrawal; this is sometimes known as the “tie” or “copulatory lock”. The male dog rapidly thrust into the female for 1–2 minutes then dismounts with the erect penis still inside the vagina, and turns to stand rear-end to rear-end with the bitch for up to 30 to 40 minutes; the penis is twisted 180 degrees in a lateral plane. During this time, prostatic fluid is ejaculated.[46]

The bitch can bear another litter within 8 months of the previous one. Dogs are polygamous in contrast to wolves that are generally monogamous. Therefore, dogs have no pair bonding and the protection of a single mate, but rather have multiple mates in a year. The consequence is that wolves put a lot of energy into producing a few pups in contrast to dogs that maximize the production of pups. This higher pup production rate enables dogs to maintain or even increase their population with a lower pup survival rate than wolves, and allows dogs a greater capacity than wolves to grow their population after a population crash or when entering a new habitat. It is proposed that these differences are an alternative breeding strategy, one adapted to a life of scavenging instead of hunting.[47]

Parenting and early life[modifier | modifier le code]

All of the wild members of the genus Canis display complex coordinated parental behaviors. Wolf pups are cared primarily by their mother for the first 3 months of their life when she remains in the den with them while they rely on her milk for sustenance and her presence for protection. The father brings her food. Once they leave the den and can chew, the parents and pups from previous years regurgitate food for them. Wolf pups become independent by 5 to 8 months, although they often stay with their parents for years. In contrast, dog pups are cared for by the mother and rely on her for milk and protection but she gets no help from the father nor other dogs. Once pups are weaned around 10 weeks they are independent and receive no further maternal care.[47]

Behavior problems[modifier | modifier le code]

A survey of 203 dog owners in Melbourne, Australia, found that the main behaviour problems reported by owners were overexcitement (63%) and jumping up on people (56%).[48]

Separation anxiety[modifier | modifier le code]

When dogs are separated from humans, usually the owner, they often display behaviours such as destructiveness, faecal or urinary elimination, hypersalivation or vocalisation. Dogs from single-owner homes are approximately 2.5 times more likely to have separation anxiety compared to dogs from multiple-owner homes. Furthermore, sexually intact dogs are only one third as likely to have separation anxiety as neutered dogs. The sex of dogs and whether there is another pet in the home do not have an effect on separation anxiety.[49]

Tail chasing[modifier | modifier le code]

Tail chasing can be classified as a stereotypy. In one clinical study on the behaval problem, 18 tail-chasing terriers were given clomipramine orally at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/kg (0.5 to 0.9 mg/lb) of body weight, every 12 hours. Three of the dogs required treatment at a slightly higher dosage range to control tail chasing, however, after 1 to 12 weeks of treatment, 9 of 12 dogs were reported to have a 75% or greater reduction in tail chasing.[50]

Behavior compared to other canids[modifier | modifier le code]

Comparisons made within the wolf-like canids allows the identification of those behaviors that may have been inherited from common ancestry and those that may have been the result of domestication or other relatively recent environmental changes.[42] Studies of free-ranging African Basenjis and New Guinea Singing Dogs indicate that their behavioral and ecological traits were the result of environmental selection pressures or selective breeding choices and not the result of artificial selection imposed by humans.[51]

Tameness[modifier | modifier le code]

Unlike other domestic species which were primarily selected for production-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors.[52][53] In 2016, a study found that there were only 11 fixed genes that showed variation between wolves and dogs. These gene variations were unlikely to have been the result of natural evolution, and indicate selection on both morphology and behavior during dog domestication. These genes have been shown to have an impact on the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response[54][53] (i.e. selection for tameness), and emotional processing.[53] Dogs generally show reduced fear and aggression compared to wolves. [55][53] Some of these genes have been associated with aggression in some dog breeds, indicating their importance in both the initial domestication and then later in breed formation.[53]

Social structure[modifier | modifier le code]

Among canids, packs are the social units that hunt, rear young and protect a communal territory as a stable group and their members are usually related.[56] Members of the feral dog group are usually not related. Feral dog groups are composed of a stable 2-6 members compared to the 2-15 member wolf pack whose size fluctuates with the availability of prey and reaches a maximum in winter time. The feral dog group consists of monogamous breeding pairs compared to the one breeding pair of the wolf pack. Agonistic behavior does not extend to the individual level and does not support a higher social structure compared to the ritualized agonistic behavior of the wolf pack that upholds its social structure. Feral pups have a very high mortality rate that adds little to the group size, with studies showing that adults are usually killed through accidents with humans, therefore other dogs need to be co-opted from villages to maintain stable group size.[42]

Socialization[modifier | modifier le code]

The critical period for socialization begins with walking and exploring the environment. Dog and wolf pups both develop the ability to see, hear and smell at 4 weeks of age. Dogs begin to explore the world around them at 4 weeks of age with these senses available to them, while wolves begin to explore at 2 weeks of age when they have the sense of smell but are functionally blind and deaf. The consequences of this is that more things are novel and frightening to wolf pups. The critical period for socialization closes with the avoidance of novelty, when the animal runs away from - rather than approaching and exploring - novel objects. For dogs this develops between 4 and 8 weeks of age. Wolves reach the end of the critical period after 6 weeks, after which it is not possible to socialize a wolf.[47]

Dog puppies require as little as 90 minutes of contact with humans during their critical period of socialization to form a social attachment. This will not create a highly social pet but a dog that will solicit human attention.[57] Wolves require 24 hours contact a day starting before 3 weeks of age. To create a socialized wolf the pups are removed from the den at 10 days of age, kept in constant human contact until they are 4 weeks old when they begin to bite their sleeping human companions, then spend only their waking hours in the presence of humans. This socialization process continues until age 4 months, when the pups can join other captive wolves but will require daily human contact to remain socialized. Despite this intensive socialization process, a well-socialized wolf will behave differently to a well-socialized dog and will display species-typical hunting and reproductive behaviors, only closer to humans than a wild wolf. These wolves do not generalize their socialization to all humans in the same manner as a socialized dog and they remain more fearful of novelty compared to socialized dogs.[58]

In 1982, a study to observe the differences between dogs and wolves raised in similar conditions took place. The dog puppies preferred larger amounts of sleep at the beginning of their lives, while the wolf puppies were much more active. The dog puppies also preferred the company of humans, rather than their canine foster mother, though the wolf puppies were the exact opposite, spending more time with their foster mother. The dogs also showed a greater interest in the food given to them and paid little attention to their surroundings, while the wolf puppies found their surroundings to be much more intriguing than their food or food bowl. The wolf puppies were observed taking part in antagonistic play at a younger age, while the dog puppies did not display dominant/submissive roles until they were much older. The wolf puppies were rarely seen as being aggressive to each other or towards the other canines. On the other hand, the dog puppies were much more aggressive to each other and other canines, often seen full-on attacking their foster mother or one another.[59]

Cognition[modifier | modifier le code]

Despite claims that dogs show more human-like social cognition than wolves,[60][61][62] several recent studies have demonstrated that if wolves are properly socialized to humans and have the opportunity to interact with humans regularly, then they too can succeed on some human-guided cognitive tasks,[63][64][65][66][67] in some cases out-performing dogs at an individual level.[68] Similar to dogs, wolves can also follow more complex point types made with body parts other than the human arm and hand (e.g. elbow, knee, foot).[67] Both dogs and wolves have the cognitive capacity for prosocial behavior toward humans; however it is not guaranteed. For canids to perform well on traditional human-guided tasks (e.g. following the human point) both relevant lifetime experiences with humans - including socialization to humans during the critical period for social development - and opportunities to associate human body parts with certain outcomes (such as food being provided by human hands, a human throwing or kicking a ball, etc.) are required.[69]

After undergoing training to solve a simple manipulation task, dogs that are faced with an insoluble version of the same problem look at the human, while socialized wolves do not.[62]

Reproduction[modifier | modifier le code]

Dogs reach sexual maturity and can reproduce during their first year in contrast to a wolf at two years. The dog female can bear another litter within 8 months of the last one. The canid genus is influenced by the photoperiod and generally reproduces in the springtime.[42] Domestic dogs are not reliant on seasonality for reproduction in contrast to the wolf, coyote, Australian dingo and African basenji that may have only one, seasonal, estrus each year.[46] Feral dogs are influenced by the photoperiod with around half of the breeding females mating in the springtime, which is thought to indicate an ancestral reproductive trait not overcome by domestication,[42] as can be inferred from wolves[70] and Cape hunting dogs.[71]

Domestic dogs are polygamous in contrast to wolves that are generally monogamous. Therefore, domestic dogs have no pair bonding and the protection of a single mate, but rather have multiple mates in a year. There is no paternal care in dogs as opposed to wolves where all pack members assist the mother with the pups. The consequence is that wolves put a lot of energy into producing a few pups in contrast to dogs that maximize the production of pups. This higher pup production rate enables dogs to maintain or even increase their population with a lower pup survival rate than wolves, and allows dogs a greater capacity than wolves to grow their population after a population crash or when entering a new habitat. It is proposed that these differences are an alternative breeding strategy adapted to a life of scavenging instead of hunting.[47] In contrast to domestic dogs, feral dogs are monogamous. Domestic dogs tend to have a litter size of 10, wolves 3, and feral dogs 5-8. Feral pups have a very high mortality rate with only 5% surviving at the age of one year, and sometimes the pups are left unattended making them vulnerable to predators.[42] Domestic dogs stand alone among all canids for a total lack of paternal care.[72]

Dogs differ from wolves and most other large canid species as they generally do not regurgitate food for their young, nor the young of other dogs in the same territory.[73] However, this difference was not observed in all domestic dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females for the young, as well as care for the young by the males, has been observed in domestic dogs, dingos and in feral or semi-feral dogs. In one study of a group of free-ranging dogs, for the first 2 weeks immediately after parturition the lactating females were observed to be more aggressive to protect the pups. The male parents were in contact with the litters as ‘guard’ dogs for the first 6–8 weeks of the litters’ life. In absence of the mothers, they were observed to prevent the approach of strangers by vocalizations or even by physical attacks. Moreover, one male fed the litter by regurgitation showing the existence of paternal care in some free-roaming dogs[74]

Space[modifier | modifier le code]

Space used by feral dogs is not dissimilar from most other canids in that they use defined traditional areas (home ranges) that tend to be defended against intruders, and have core areas where most of their activities are undertaken. Urban domestic dogs have a home range of 2-61 hectares in contrast to a feral dogs home range of 58 square kilometers. Wolf home ranges vary from 78 square kilometers where prey is deer to 2.5 square kilometers at higher latitudes where prey is moose and caribou. Wolves will defend their territory based on prey abundance and pack density, however feral dogs will defend their home ranges all year. Where wolf ranges and feral dog ranges overlap, the feral dogs will site their core areas closer to human settlement.[42]

Predation[modifier | modifier le code]

Despite claims in the popular press, studies could not find evidence of a single predation on cattle by feral dogs.[42][75][76] However, domestic dogs were responsible for the death of 3 calves over one 5-year study.[76] Other studies in Europe and North America indicate only limited success in the consumption of wild boar, deer and other ungulates, however it could not be determined if this was predation or scavenging on carcasses. Studies have observed feral dogs conducting brief, uncoordinated chases of small game with constant barking - a technique without success.[42]

In 2004, a study reviewed 5 other studies of feral dogs published between 1975 and 1995 and concluded that their pack structure is very loose and rarely involves any cooperative behavior, either in raising young or in obtaining food.[77] Feral dogs are primarily scavengers, with studies showing that unlike their wild cousins, they are poor ungulate hunters, having little impact on wildlife populations where they are sympatric.[78]:267 However, several garbage dumps located within the feral dog's home range are important for their survival.[79]

Dogs in human society[modifier | modifier le code]

Dogs likely were the first animals to be domesticated and as such have shared a common environment with humans for over ten thousand years. Only recently, however, has this species' behavior been subject to scientific scrutiny. Most of this work has been inspired by research in human cognitive psychology and suggests that in many ways dogs are more human-like than any other species, including nonhuman primates.[80]{{copyvio link}}

Studies using an operant framework have indicated that humans can influence the behavior of dogs through food, petting and voice. Food and 20–30 seconds of petting maintained operant responding in dogs.[81] Some dogs will show a preference for petting once food is readily available, and dogs will remain in close proximity to a person providing petting and show no satiation to that stimulus.[82] Petting alone was sufficient to maintain the operant response of military dogs to voice commands, and responses to basic obedience commands in all dogs increased when only vocal praise was provided for correct responses.[83]

A study using dogs that were trained to remain motionless while unsedated and unrestrained in an MRI scanner exhibited caudate activation to a hand signal associated with reward.[2] Further work found that the magnitude of the canine caudate response is similar to that of humans, while the between-subject variability in dogs may be less than humans.[84] In a further study, 5 scents were presented (self, familiar human, strange human, familiar dog, strange dog). While the olfactory bulb/peduncle was activated to a similar degree by all the scents, the caudate was activated maximally to the familiar human. Importantly, the scent of the familiar human was not the handler, meaning that the caudate response differentiated the scent in the absence of the person being present. The caudate activation suggested that not only did the dogs discriminate that scent from the others, they had a positive association with it. Although these signals came from two different people, the humans lived in the same household as the dog and therefore represented the dog's primary social circle. And while dogs should be highly tuned to the smell of items that are not comparable, it seems that the “reward response” is reserved for their humans.[85]

Research has shown that there are individual differences in the interactions between dogs and their human that have significant effects on dog behavior. In 1997, a study showed that the type of relationship between dog and master, characterized as either companionship or working relationship, significantly affected the dog's performance on a cognitive problem-solving task. They speculate that companion dogs have a more dependent relationship with their owners, and look to them to solve problems. In contrast, working dogs are more independent.[86]

Dogs in the family[modifier | modifier le code]

Dogs at work[modifier | modifier le code]

Service dogs are those that are trained to help people with disabilities. Detection dogs are trained to using their sense of smell to detect substances such as explosives, illegal drugs, wildlife scat, or blood. In science, dogs have helped humans understand about the conditioned reflex. Attack dogs, dogs that have been trained to attack on command, are employed in security, police, and military roles.

Attacks[modifier | modifier le code]

Erreur : La version française équivalente de {{Main}} est {{Article détaillé}}.

The human-dog relationship is based on unconditional trust, however if this trust is lost it will be difficult to reinstate. As a last resort, humans will use a slap but a dog will use a bite. A dog's thick fur protects it from the bite of another dog but humans are furless and are not so protected.[87]

In the UK between 2005 and 2013, there were 17 fatal dog attacks. In 2007-08 there were 4,611 hospital admissions due to dog attacks, which increased to 5,221 in 2008-09. It has been estimated that more than 200,000 people a year are bitten by dogs in England, with the annual cost to the National Health Service of treating injuries about £3 million.[88] A report published in 2014 stated there were 6,743 hospital admissions specifically caused by dog bites, a 5.8% increase from the 6,372 admissions in the previous 12 months.[89]

In the US between 1979 and 1996, there were more than 300 human dog bite-related fatalities.[90] In the US in 2013, there were 31 dog-bite related deaths. Each year, more than 4.5 million people in the US are bitten by dogs and almost 1 in 5 require medical attention.[91]

Attack training is condemned by some as promoting ferocity in dogs; a 1975 American study showed that 10% of dogs that have bitten a person received attack dog training at some point.[92]

See also[modifier | modifier le code]

- Gray wolf#Behavior

- Alpha roll

- Dog communication

- Dog intelligence

- Pack (canine)

- Pack hunter

- Separation anxiety disorder (humans)

Notes et références[modifier | modifier le code]

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Dog behavior » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Daniel Levitis, William Z. Lidicker, Jr, Glenn Freund et Glenn Freund, « Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour », Animal Behaviour, vol. 78, , p. 103–10 (DOI 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018, lire en ligne)

- G. S. Berns, A. M. Brooks et M. Spivak, « Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs », PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no 5, , e38027 (PMID 22606363, PMCID 3350478, DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0038027, Bibcode 2012PLoSO...738027B)

- M. Tomasello et J. Kaminski, « Like Infant, Like Dog », Science, vol. 325, no 5945, , p. 1213–4 (PMID 19729645, DOI 10.1126/science.1179670)

- P. Skoglund, E. Ersmark, E. Palkopoulou et L. Dalén, « Ancient Wolf Genome Reveals an Early Divergence of Domestic Dog Ancestors and Admixture into High-Latitude Breeds », Current Biology, vol. 25, no 11, , p. 1515–9 (PMID 26004765, DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019)

- Juliane Kaminski, Josep Call et Julia Fischer, « Word Learning in a Domestic Dog: Evidence for "Fast Mapping" », Science, vol. 304, no 5677, , p. 1682–3 (ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 15192233, DOI 10.1126/science.1097859, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- (en) Coren, Stanley, How Dogs Think, First Free Press, Simon & Schuster, (ISBN 0-7432-2232-6)

- (en) Coren, Stanley, How Dogs Think, First Free Press, Simon & Schuster, (ISBN 0-7432-2232-6)

- (en) A&E Television Networks, Big Dogs, Little Dogs: The companion volume to the A&E special presentation, GT Publishing, coll. « A Lookout Book », (ISBN 1-57719-353-9)

- (en) Alderton, David, The Dog, Chartwell Books, (ISBN 0-89009-786-0)

- Jennifer Davis, « Dr. P's Dog Training: Vision in Dogs & People », (consulté le )

- Glenn Elert et Timothy Condon, « Frequency Range of Dog Hearing », The Physics Factbook, (consulté le )

- « How well do dogs and other animals hear » (consulté le )

- « Dog Sense of Hearing », seefido.com (consulté le )

- Coren, Stanley "How To Speak Dog: Mastering the Art of Dog-Human Communication" 2000 Simon & Schuster, New York.

- Horowitz, A., « Attention to attention in domestic dog Canis familiaris dyadic play », Animal Cognition, vol. 12, no 1, , p. 107–118 (PMID 18679727, DOI 10.1007/s10071-008-0175-y)

- Ward, C., Bauer, E.B. and Smuts, B.B., « Partner preferences and asymmetries in social play among domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, littermates », Animal Behaviour, vol. 76, no 4, , p. 1187–1199 (DOI 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.06.004)

- Rooney, N.J., Bradshaw, J.W.S. and Robinson, I.H., « A comparison of dog–dog and dog–human play behaviour », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 66, no 3, , p. 235–248 (DOI 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00078-7)

- Rooney, N.J. and Bradshaw, Jv.W.S., « Links between play and dominance and attachment dimensions of dog-human relationships », Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 6, no 2, , p. 67–94 (PMID 12909524, DOI 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0602_01)

- Horváth, Z., Dóka, A. and Miklósi A., « Affiliative and disciplinary behavior of human handlers during play with their dog affects cortisol concentrations in opposite directions », Hormones and Behavior, vol. 54, no 1, , p. 107–114 (PMID 18353328, DOI 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.002)

- Deborah Custance et Jennifer Mayer, « Empathic-like responding by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to distress in humans: an exploratory study », Animal Cognition, vol. 15, no 5, , p. 851–859 (PMID 22644113, DOI 10.1007/s10071-012-0510-1, lire en ligne)

- (en) « Behaviour problems linked to pessimistic dogs », Sydney Morning Herald, (lire en ligne)

- R. R. McCrae, P.T Costa, F. Ostendorf, A. Angleitner, M. Hřebíčková, M. D. Avia et P.R. Saunders, « Nature over nurture: temperament, personality, and life span development », Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 78, no 1, , p. 173–86 (PMID 10653513, DOI 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.173)

- A. C. Jones et S. D. Gosling, « Temperament and personality in dogs (Canis familiaris): a review and evaluation of past research. », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 95, no 1, , p. 1–53 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.04.008)

- M. C. Gartner, « Pet personality: A review. », Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 75, , p. 102–113 (DOI 10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.042)

- R. R. McCrae et P. T. Costa, « A five-factor theory of personality. », Handbook of personality: Theory and research, vol. 2, , p. 139–153

- J. L. Fratkin, D. L. Sinn, E. A. Patal et S. D. Gosling, « Personality consistency in dogs: a meta-analysis », PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no 1, , e54907 (PMID 23372787, PMCID 3553070, DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0054907)

- J. Vas, C. Müller, B. Győri et Á. Miklósi, « Consistency of dogs’ reactions to threatening cues of an unfamiliar person. », Applied animal behaviour science, vol. 112, no 3, , p. 331–344 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.09.002)

- Y. Hu et J. A. Serpell, « Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs », Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, vol. 223, no 9, , p. 1293–1300 (PMID 14621216, DOI 10.2460/javma.2003.223.1293)

- R. H. De Meester, D. De Bacquer, K. Peremans, S. Vermeire, D. J. Planta, F. Coopman et K. Audenaert, « A preliminary study on the use of the Socially Acceptable Behavior test as a test for shyness/confidence in the temperament of dogs. », Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, vol. 3, no 4, , p. 161–170 (DOI 10.1016/j.jveb.2007.10.005)

- S. Barnard, C. Siracusa, I. Reisner, P. Valsecchi et J. A. Serpell, « Validity of model devices used to assess canine temperament in behavioral tests. », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 138, no 1, , p. 79–87 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.017)

- Svartberga, K. and Forkman, B., « Personality traits in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 79, no 2, , p. 133–155 (DOI 10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00121-1)

- K Svartberg, I Tapper, H Temrin, T Radesater et S Thorman, « Consistency of personality traits in dogs », Animal Behaviour, vol. 69, no 2, , p. 283–291 (DOI 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.04.011)

- K. Svartberg et J. Topál, « Personality traits in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). », Applied animal behaviour science, vol. 79, no 2, , p. 133–155 (DOI 10.1016/s0168-1591(02)00121-1)

- E. Wilsson et P. E. Sundgreen, « The use of a behaviour test for the selection of dogs for service and breeding, I: Method of testing and evaluating test results in the adult dog, demands on different kinds of service dogs, sex and breed differences. », Applied animal behaviour science, vol. 53, no 4, , p. 279–295 (DOI 10.1016/s0168-1591(96)01174-4)

- D. L. Duffy et J. A. Serpell, « Behavioral assessment of guide and service dogs. », Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, vol. 3, no 4, , p. 186–188 (DOI 10.1016/j.jveb.2007.12.010)

- K. S. Bollen et J. Horowitz, « Behavioral evaluation and demographic information in the assessment of aggressiveness in shelter dogs. », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 112, no 1, , p. 120–135 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.07.007)

- S. Riemer, C. Müller, Z. Virányi, L. Huber et F. Range, « Choice of conflict resolution strategy is linked to sociability in dog puppies. », Applied animal behaviour science, vol. 149, no 1, , p. 36–44 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2013.09.006)

- Carlos Drews, « The Concept and Definition of Dominance in Animal Behaviour », Behaviour, vol. 125, no 3, , p. 283–313 (DOI 10.1163/156853993X00290)

- John W.S. Bradshaw, Emily J. Blackwell et Rachel A. Casey, « Dominance in domestic dogs—useful construct or bad habit? », Journal of Veterinary Behavior, vol. 4, no 3, , p. 135–144 (DOI 10.1016/j.jveb.2008.08.004, lire en ligne [PDF])

- P. Pongrácz, V. Vida, P. Bánhegyi et Á. Miklósi, « How does dominance rank status affect individual and social learning performance in the dog (Canis familiaris)? », Animal Cognition, Springer, vol. 11, no 1, , p. 75–82 (ISSN 1435-9456, PMID 17492317, DOI 10.1007/s10071-007-0090-7)

- John W.S. Bradshaw et Amanda M. Lea, « Dyadic Interactions Between Domestic Dogs », Anthrozoös, vol. 5, no 4, , p. 245–253 (DOI 10.2752/089279392787011287)

- « Comparative social ecology of feral dogs and wolves », Ethology Ecology & Evolution, vol. 7, no 1, , p. 49–72 (DOI 10.1080/08927014.1995.9522969, lire en ligne [PDF])

- (en) Coppinger, Ray, Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution, New York, Scribner, (ISBN 0-684-85530-5)

- Kaulfuß, P. and Mills, D.S., « Neophilia in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and its implication for studies of dog cognition », Animal Cognition, vol. 11, no 3, , p. 553–556 (PMID 18183436, DOI 10.1007/s10071-007-0128-x)

- "40 Winks?" Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic Vol. 220, No. 1. July 2011.

- « Canine and feline reproduction and contraception », Michelson Prize and Grants (consulté le )

- K. Lord, « A Comparison of the Sensory Development of Wolves (Canis lupus lupus) and Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) », Ethology, vol. 119, no 2, , p. 110–120 (DOI 10.1111/eth.12044)

- Kobelt, A.J., Hemsworth, P.H., Barnett, J.L. and Coleman, G.J., « A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia—conditions and behaviour problems », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 82, no 2, , p. 137–148 (DOI 10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00062-5)

- Flannigan, G. and Dodman, N.H.A, « Risk factors and behaviors associated with separation anxiety in dogs », Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, vol. 219, no 4, , p. 460–466 (PMID 11518171, DOI 10.2460/javma.2001.219.460)

- « Description and development of compulsive tail chasing in terriers and response to clomipramine treatment », Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, vol. 212, no 8, , p. 1252–1257 (PMID 9569164)

- « Primitive dogs, their ecology and behavior: Unique opportunities to study the early development of the human-canine bond », Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, vol. 210, no 8, , p. 1122–1126 (PMID 9108912)

- Serpell J, Duffy D. Dog Breeds and Their Behavior. In: Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014

- Alex Cagan et Torsten Blass, « Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by selection during dog domestication », BMC Evolutionary Biology, vol. 16, (DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7)

- Almada RC, Coimbra NC. Recruitment of striatonigral disinhibitory and nigrotectal inhibitory GABAergic pathways during the organization of defensive behavior by mice in a dangerous environment with the venomous snake Bothrops alternatus [ Reptilia , Viperidae ] Synapse 2015:n/a–n/a

- Coppinger R, Schneider R: Evolution of working dogs. The domestic dog: Its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1995.

- Mech, L. D. 1970. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. Natural History Press (Doubleday Publishing Co., N.Y.) 389 pp. (Reprinted in paperback by University of Minnesota Press, May 1981)

- Daniel G. Freedman, John A. King et Orville Elliot, « Critical Period in the Social Development of Dogs », Science, vol. 133, no 3457, , p. 1016–1017 (DOI 10.1126/science.133.3457.1016, Bibcode 1961Sci...133.1016F)

- (en) Klinghammer, E., & Goodmann, P. A., Man and wolf: Advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research, Dordrecht: W. Junk, , « Socialization and management of wolves in captivity »

- Frank H et Frank MG, « On the effects of domestication on canine social development and behavior », Applied Animal Ethology, vol. 8, no 6, , p. 507–525 (DOI 10.1016/0304-3762(82)90215-2)

- B. Hare, « The Domestication of Social Cognition in Dogs », Science, vol. 298, no 5598, , p. 1634–6 (PMID 12446914, DOI 10.1126/science.1072702, Bibcode 2002Sci...298.1634H)

- Brian Hare et Michael Tomasello, « Human-like social skills in dogs? », Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 9, no 9, , p. 439–444 (PMID 16061417, DOI 10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.003)

- Adam Miklósi, Kubinyi, E, Topál, J, Gácsi, M, Virányi, Z et Csányi, V., « A simple reason for a big difference: wolves do not look back at humans, but dogs do », Current Biology ;13(9), vol. 13, no 9, , p. 763–766 (PMID 12725735, DOI 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00263-X)

- M Gácsi, B Gyori, Z Viranyi, E Kubinyi, F Range, B Belenyi et Á Miklósi, « Explaining dog wolf differences in utilizing human pointing gestures: Selection for synergistic shifts in the development of some social skills », PLoS ONE, vol. 4, no 8, , e6584 (DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0006584, Bibcode 2009PLoSO...4.6584G)

- F. Range et Z. Virányi, « Development of gaze following abilities in wolves (Canis lupus) », PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no 2, , e16888 (PMID 21373192, DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0016888, Bibcode 2011PLoSO...616888R)

- « Wolves outperform dogs in following human social cues », Animal Behaviour, vol. 76, no 6, , p. 1767–1773 (DOI 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.028)

- « Can your dog read your mind? Understanding the causes of canine perspective taking », Learning & Behavior, vol. 39, no 4, , p. 289–302 (DOI 10.3758/s13420-011-0034-6)

- « Human-Socialized Wolves Follow Diverse Human Gestures... And They May Not Be Alone », International Journal of Comparative Psychology, vol. 25, no 2, , p. 97–117 (lire en ligne)

- Udell, R. F. Giglio et C. D. Wynne, « Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) use human gestures but not nonhuman tokens to find hidden food », Journal of Comparative Psychology, vol. 122, no 1, , p. 84–93 (PMID 18298285, DOI 10.1037/0735-7036.122.1.84)

- (en) Udell, M.A.R., Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, (DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-53994-7_10, lire en ligne), « 10. A Dog’s-Eye View of Canine Cognition »

- U. S. Seal et L. D. Mech, « Blood Indicators of Seasonal Metabolic Patterns in Captive Adult Gray Wolves », The Journal of Wildlife Management, The Wildlife Society, vol. 47, no 3, , p. 704–715 (DOI 10.2307/3808606, JSTOR 3808606)

- D. J. Cunningham, « Cape Hunting Dogs (Lycaon pictus) in the Gardens of the Royal Zoological Society of Ireland », Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 25, no 2, , p. 843–848 (DOI 10.1017/S0370164600016667, lire en ligne)

- (en) Devra G. Kleiman et James R. Malcom, Parental Care in Mammals, Plenum Press, , 347–387 p. (ISBN 9780306405334, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4613-3150-6_9), « The Evolution of Male Parental Investment in Mammals »

- (en) Coppinger, Ray, Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution, New York, Scribner, (ISBN 0-684-85530-5)

- S. K. Pal, « Parental care in free-ranging dogs, Canis familiaris », Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 90, , p. 31–47 (DOI 10.1016/j.applanim.2004.08.002)

- M. Douglas Scott et Keith Causey, « Ecology of Feral Dogs in Alabama », The Journal of Wildlife Management, The Wildlife Society, vol. 37, no 3, , p. 253–265 (DOI 10.2307/3800116, JSTOR 3800116)

- (en) William H. Nesbitt, Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology & Evolution, reprinted, (ISBN 978-1-929242-64-1), « Ecology of a Feral Dog Pack on a Wildlife Refuge », p. 391

- W. van Kerkhove, « A Fresh Look at the Wolf-Pack Theory of Companion-Animal Dog Social Behavior », Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 7, no 4, , p. 279–285 (DOI 10.1207/s15327604jaws0704_7)

- (en) J. Clutton-Brock, The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, , 7–20 p. (ISBN 9780521425377), « Origins of the dog: Domestication and early history »

- (en) D. W. Macdonald et G. M. Carr, The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, , 199–216 p. (ISBN 9780521425377), « Variation in dog society: Between resource dispersion and social flux »

- Monique A.R Udell et C.D.L Wynne, « A Review of Domestic Dogs' (Canis Familiaris) Human-Like Behaviors: Or Why Behavior Analysts Should Stop Worrying and Love Their Dogs », Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, vol. 89, no 2, , p. 247–61 (PMID 18422021, DOI 10.1901/jeab.2008.89-247)

- E. Fonberg, E. Kostarczyk et J. Prechtl, « Training of Instrumental Responses in Dogs Socially Reinforced by Humans », The Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science, vol. 16, no 4, , p. 183–193 (PMID 7329743)

- E. N. Feuerbacher et C. D. L. Wynne, « Shut up and pet me! Domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) prefer petting to vocal praise in concurrent and single-alternative choice procedures », Behavioural Processes, vol. 110, , p. 47–59 (PMID 25173617, DOI 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.019)

- Roger W. McIntire et Thomas A. Colley, « Social Reinforcement In The Dog », Psychological Reports, vol. 20, no 3, , p. 843–846 (PMID 6042498, DOI 10.2466/pr0.1967.20.3.843)

- G. S. Berns, A. Brooks et M. Spivak, « Replicability and Heterogeneity of Awake Unrestrained Canine fMRI Responses », PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no 12, , e81698 (PMID 24324719, PMCID 3852264, DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0081698, Bibcode 2013PLoSO...881698B)

- G. S. Berns, A. M. Brooks et M. Spivak, « Scent of the familiar: An fMRI study of canine brain responses to familiar and unfamiliar human and dog odors », Behavioural Processes, vol. 110, , p. 37–46 (PMID 24607363, DOI 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.02.011)

- Topál, J., Miklósi, Á. and Csányi, V., « Dog-human relationship affects problem solving behavior in the dog », Anthrozoös, vol. 10, no 4, , p. 214–224 (DOI 10.2752/089279397787000987, lire en ligne)

- (en) Ádám Miklósi, Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition, Oxford, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 9780199295852, DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199295852.001.0001)

- (en) Prynne, M., « Dog attack laws and statistics », The Telegraph, {{Article}} : paramètre «

date» manquant (lire en ligne) - « Dog bite hospitalisations highest in deprived areas », NHS Choices, (consulté le )

- J.J. Sacks, L Sinclair, J Gilchrist, G. C. Golab et R Lockwood, « Breeds of dogs involved in fatal human attacks between 1979 and 1998 », JAVMA, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, vol. 217, no 6, , p. 836–840 (PMID 10997153, DOI 10.2460/javma.2000.217.836, lire en ligne [PDF], consulté le )

- « Infographic: Dog bites by the numbers », AVMA, (consulté le )

- (en) United States Congress. Senate. Committee on Commerce. Subcommittee on the Environment, Animal Welfare Improvement Act of 1975: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on the Environment of the Committee on Commerce, United States Government, , p. 111 :

« Nearly 10 per cent of the dogs that have bitten people have received attack dog training. »

{{Domestic dog}}

Further reading[modifier | modifier le code]

- Hare, Brian & Woods, Venessa. The Genius of Dogs (2013 Penguin Publishing Group) Reveals research findings about how dogs think and how we humans can have deeper relationships with them.

- Miklosi, Adam. Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition (2007 Oxford University Press) Provides a basis for a complete dog behavioural biology based on concepts derived from contemporary ethology.

- Pet Behavior articles from the ASPCA