Utilisateur:Thib Phil/Bac à sable

Cette page est un espace de travail Fichier:Tecleando.gif

Arme blindée britannique[modifier | modifier le code]

By the early 20th century, armoured cars were invented, but proved incapable of accommodating open-country terrain or rugged battlefields. The first tank projects started to appear, providing for powerful artillery, strong protection and all-terrain traction, with the first project of Levavasseur and the landship concept of H. G. Wells. Full development of the tank would start in the First World War.

The first use of tanks in battle was made by the British Army during World War 1 in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (the third and final offensive mounted by the British during the Battle of the Somme) which commenced on the 15th of September 1916.

Première Guerre mondiale : naissance de l' « Armoured Corps »[modifier | modifier le code]

The father of the tank. Col. Ernest Swinton of the British Royal Engineers « invented » the tank in the early years of W.W. I. After reading an article on American agricultural tractors, Swinton obtained one of these and encased it in metal armor. Swinton's primitive tank impressed the War Office, which assigned Lt. W. G. Wilson to further develop the invention.

Entre-deux-guerres[modifier | modifier le code]

Les théoriciens britanniques de l' « Armoured Warfare »[modifier | modifier le code]

Mécanisation de la cavalerie[modifier | modifier le code]

Le « Royal Tank Regiment »[modifier | modifier le code]

Les matériels : « tankettes », « light tanks », « cruiser tanks » et « infantry tanks »[modifier | modifier le code]

Seconde Guerre mondiale[modifier | modifier le code]

Premières campagnes[modifier | modifier le code]

- Les blindés de la « British Expeditionary Force » en France.

- Balkans et Afrique du Nord en 1941

-

Mk VIC knocked out during an engagement on 27 May 1940 in the Somme sector.

Crise et reconstruction[modifier | modifier le code]

The British Army only had 100 tanks left after Dunkirk and Vauxhall Motors were under instructions to produce the tanks as quickly as possible.

-

« Beaverette »

- Les matériels américains.

La reconquête alliée (1942 - 1945)[modifier | modifier le code]

Organisation des unités blindées britanniques pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale[modifier | modifier le code]

- Armoured/Tank brigades

Unités typiquement britanniques dont le principe fondateur remonte au concept de char d'accompagnement de la Première Guerre mondiale, les Tank brigades - initialement intitulées Armoured Brigades - ont été créées dans le but de fournir des unités d'appui blindées aux divisions d'infanterie[note 1], les modules constituant ces brigades pouvant être ponctuellement détachés en appui d'une unité d'infanterie particulière jusqu'au niveau de la compagnie.

Ces brigades sont articulées autour de trois régiments de chars d'infanterie Churchill auxquels viennent s'adjoindre des unités techniques de réparation et d'intendance. Chaque régiment comprenait un RHQ troop d'État-major régimentaire de quatre Churchill, un Recce troop (reconnaissance) de douze chars Stuart et trois escadrons de 16 chars (dont au moins un Close Support (CS) armé d'un obusier de 95 mm) en plus d'unités de dépannage et de transport.

Guerre froide et guerres de décolonisation[modifier | modifier le code]

Les chars de la Guerre froide[modifier | modifier le code]

Le « Centurion » et le « Conqueror »[modifier | modifier le code]

FV 4201 « Chieftain »[modifier | modifier le code]

Blindés légers[modifier | modifier le code]

Les unités blindées britanniques de la Guerre froide[modifier | modifier le code]

- « British Army Of the Rhine » et « Berlin Brigade ».

Les blindés au combat[modifier | modifier le code]

L'Après-guerre-froide[modifier | modifier le code]

« FV 4030 Challenger I MBT » et « FV 4034 Challenger II MBT »[modifier | modifier le code]

Articles connexes[modifier | modifier le code]

Bibliographie[modifier | modifier le code]

Liens externes[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes et références[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

- Les divisions d'infanterie US disposaient d'un bataillon organique de char

Références[modifier | modifier le code]

Infanterie mécanisée britannique[modifier | modifier le code]

Infanterie motorisée et infanterie mécanisée[modifier | modifier le code]

Première Guerre mondiale[modifier | modifier le code]

Arguably, the first mechanized infantry were 36 two-man infantry squads carried forward by Mark V* tanks at the Battle of Amiens in 1918. In a battle of such scale, their contribution went unnoticed.

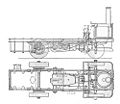

The first true APC was the Mark IX, these were troop carriers or infantry supply vehicles - among the first tracked Armoured personnel carrier not counting experiments with the lengthened Mk V's. 34 were built out of an order for 200. Officially these vehicles could carry 50 men, although they had to stand up (no seats) it was more likely 30 to be carried, being a Platoon. Up to 10 tons of stores could be carried instead of men. The crew of a Mk IX consisted of a driver, a commander sitting to the right of him (the first time for a British tank, showing adaptation to the traffic conditions in France), a mechanic and a machine gunner who could man a gun in a hatch at the back. A second machine gun was fitted in the front. Along each side of the hull were eight loopholes, through which the soldiers could fire their rifles, making the Mark IX also the world's first Infantry Fighting Vehicle. Two of the loopholes were in the two oval side doors on each side. Despite using thinner (10 mm) armour plate, the weight was still 27 tons and the speed only 4 mph (7 km/h). The tank could also carry supplies in a tray on the roof behind the commander's armoured observation turret (being the highest point at 2.64 metres), while towing up to three loaded sledges. One of the first three was used as an armoured ambulance. After the end of the Great War the Mark IX's were used for some years. The type was named The Pig as the low front of the track looked like the snout of one.

Les « Motor Battalions » de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale[modifier | modifier le code]

Les matériels[modifier | modifier le code]

Bibliographie[modifier | modifier le code]

Liens externes[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes et références[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

Références[modifier | modifier le code]

Mécanisation de l'armée britannique (1899 - 1942)[modifier | modifier le code]

Armoured cars were first used by the British Army for the policing of distant colonial outposts. By the outbreak of First World War the allies in Europe were using armour-plated, open-topped vehicles with machine guns or other light guns or artillery pieces. The most popular British car was the Napier that was first produced in 1912. The design consisted of a number of alternative bodies which enabled the chassis to be adapted quickly for different roles.

The British Army invented the tank and pioneered its development during World War I, and produced the leading theorists of Armored warfare, J.F.C. Fuller and B.H. Liddell Hart, during the interwar years. After World War I, military opinion in Britain was divided on the future of tank warfare. J.F.C. Fuller was convinced that only the tank had a future on the battlefield. Basil Liddell Hart foresaw a war where all arms, infantry, tanks and artillery, would be mechanised, resembling fleets of 'land ships', and experiments in these fields did take place but were not adopted. Liddell Hart would be proved right, but it would not be for sixty years that even the wealthiest countries could make his ideas a reality

British armored forces were improperly trained for the type of combat which confronted them in World War II, primarily because « the British Army refused to change its basic strategic doctrines to maximize the potential of a new weapon of war » [1]. In the Interwar years, the ratio of armor to Infantry decreased – when it should have logically been increased. Pre-World War I military strategy was based upon the Napoleonic experience of “absolute war” and of the destruction of the opponent’s forces through unrelenting offensive pressure, the application of maximum force in the decisive attack, and “an unswerving determination by both commanders and troops to conquer at any cost.” The victory of Britain and her Allies in the Great War – a war of attrition – vindicated in the minds of the generals their faith in this conception of war, confirming their dependence upon a psychological distortion of Clausewitz. It was this dogmatic rigidity to the army’s traditional strategic doctrine, according to Robert H. Larson, which fettered innovations in British military thought during the interwar period [2].

Les débuts de la motorisation de l'armée britannique[modifier | modifier le code]

-

Le Land Ironclad, croiseur terrestre chenillé imaginé par Herbert George Wells dès 1904.

Premiers essais[modifier | modifier le code]

Seconde Guerre des Boers : The Brits started buying up every traction engine they could find to move men and supplies around the unimproved areas of South Africa. Enter John Fowler and Company, of Leeds, England. The British military turned to Mr. Fowler to build them a fleet (of 3 by the time the Boer War was over) of armored steam traction engines for use in the Boer War. Called the Fowler B.5 Armored Road Tractor, it had a 20 hp steam engine surrounded by an armored shell to protect it and the crew. It weight 15 tons with armor, and could go 10 mph on level, improved roads or about half that across fields or unimproved roads. Its range and reach was only limited by how much coal and boiler water it could carry or could be delivered to it[3].

La « Motor War Car » de Frederick Richard Simms[modifier | modifier le code]

Simms' Motor War Car was the first armoured car ever built. It was designed by F.R. Simms and a single prototype was ordered in April 1899[4] It was built by Vickers, Sons & Maxim of Barrow on a special Coventry-built Daimler chassis[4] with a German-built Daimler motor[4]. Because of difficulties, including a gearbox destroyed by a road accident, that arose during completion the prototype was not finished by Vickers until 1902[4] when the Boer War was over. The vehicle was an improvement over Simms' earlier design known as Motor Scout which was the first armed (but not armoured) vehicle powered by a petrol engine. The vehicle had Vickers armour 6 mm thick and was powered by a four cylinder 3.3 litre[4] 16 hp Cannstatt Daimler engine giving it a maximum speed of around 9 miles per hour (14.5 km/h). The armament, consisting of two Maxim guns, was carried in two turrets with 360° traverse. Some sources also mention a single QF 1 pounder pom-pom.[5][6].Fully equipped it was 28 pieds (8,5344 m) overall with a beam of 8 pieds (2,4384 m) , a ram at each end, two turrets and two guns and "capable of running on very rough surfaces".[4]It had a crew of four. Simms' Motor War Car was presented at the Crystal Palace, London, in April 1902[7][note 1].

Premier programme[modifier | modifier le code]

In the early 1900s the British Army began considering the ways that motor transport could be used during a large-scale war. It was recognised that motor transport would enable the British Army to move troops very quickly. In 1911 the British Army announced its strategy for acquiring motor transport in an emergency. An annual fee of £15 was to be paid for each lorry registered with the British Army. By 1914 this fee had been increased to £110. Dès 1912, l'armée britannique se dote d'un parc de voiture Napier dont certaines sont affectées aux transmissions télégraphiques [8] & [9].

Première Guerre mondiale[modifier | modifier le code]

When war was declared in August 1914 a total of 1,200 lorries were acquired by the Army. One of the most successful lorries used by the British Army was the Dennis 3-Ton Lorry[10].

Towards the end of World War I, all the armies involved were faced with the problem of maintaining the momentum of an attack. Tanks, artillery or infiltration tactics could all be used to break through an enemy defense, but almost all the offensives launched in 1918 ground to a halt after a few days. Pursuing infantry quickly became exhausted, and artillery, supplies and fresh formations could not be brought forward over the battlefields quickly enough to maintain the pressure on the regrouping enemy[note 2].

It was widely acknowledged that cavalry was too vulnerable to be used on most European battlefields, although many armies continued to deploy them. Motorized Infantry could maintain rapid movement, but their trucks required either a good road network, or firm open terrain (such as desert). They were unable to traverse a battlefield obstructed by craters, barbed wire and trenches. Tracked or all-wheel drive vehicles were to be the solution[note 3].

Camions et tracteurs[modifier | modifier le code]

A total of 900 of the LGOC B-type buses operated by the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) were used to move troops behind the lines during World War I[11]. After initially serving without any modifications they were painted khaki, had their windows removed, and were fitted with 2 inch thick planks to provide some limited protection[12] . Some had anti-aircraft guns attached to them, others were made into pigeon lofts to house the pigeons used for communication along the front.[12] They served until the end of the war when they were used to bring troops home[11]. The Imperial War Museum preserves one of these buses, B43, known as Ole Bill after the contemporary cartoon character.[13]

Automitrailleuses[modifier | modifier le code]

Armoured cars were used on the Western Front but they were limited in trench warfare because they could not handle very uneven terrain. The British army used armoured cars with great success in Palestine and in Mesopotamia where they were deployed in what had previously been the Cavalry role of outflanking and pursuit. In 1914, the Lanchester Armoured Car was the second most numerous armoured car in service after the Rolls-Royce. It was originally designed to support air bases and retrieve downed pilots. In 1915, the Lanchester underwent hull remodeling and was formed into armoured car squadrons. 36 Lanchesters were delivered to the Royal Naval Air Service. Three squadrons of 12 vehicles were formed and sent to France in May. One of these squadrons served with the Belgian Army. With the establishment of the mountain to coast trench system of the Western Front, armoured cars were of less use and the British Army taking over all armoured car use standardizes on the Rolls-Royce pattern. The Lanchesters were then sent to Russia in January 1916 with the RNAS expedition force. The expedition force was deployed in Caucasus, Romania and Galicia in support of the Russian forces there; detachments were sent as far as to Persia and Turkey and the Lanchesters clocked up many thousands of miles. In early 1918 the expedition force departed Russia via Murmansk.

Les Tanks[modifier | modifier le code]

Ces Landships (litt. vaisseaux de terre) doivent une grande part de leur existence aux anticipations militaires d'Albert Robida et de Herbert G. Wells[note 4], inspirées par la mise en service de ces navires de guerre ultramodernes transposée à une vision futuriste de la guerre terrestre et auquel l'impasse dans laquelle se trouvait la situation militaire de fin 1916 (après la bataille de Verdun) devait donner - au moins sur le plan purement théorique - un semblant de concrétisation.

Tanks were first employed in modern warfare in the Somme in 1916, and began to appear in significant quantities on the battlefields of Europe near the end of World War I. Perhaps the most successful use of the tank during the Great War was at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917, when armored elements were finally able to break the deadlock of trench warfare that had characterized military operations to that point. As Tom Wintringham writes in « The Story of Weapons and Tactics » : « ...at the Battle of Cambrai...they showed that they were inherently capable of offensive movement so rapid as to leave the infantry far behind them....they showed themselves capable of a decisive operation ».

Infanterie et artillerie « mécanisées »[modifier | modifier le code]

Arguably, the first mechanized infantry were 36 two-man infantry squads carried forward by Mark V* tanks at the Battle of Amiens in 1918. In a battle of such scale, their contribution went unnoticed.

The first true APC was the Mark IX, these were troop carriers or infantry supply vehicles - among the first tracked Armoured personnel carrier not counting experiments with the lengthened Mk V's. 34 were built out of an order for 200. Officially these vehicles could carry 50 men, although they had to stand up (no seats) it was more likely 30 to be carried, being a Platoon. Up to 10 tons of stores could be carried instead of men. The crew of a Mk IX consisted of a driver, a commander sitting to the right of him (the first time for a British tank, showing adaptation to the traffic conditions in France), a mechanic and a machine gunner who could man a gun in a hatch at the back. A second machine gun was fitted in the front. Along each side of the hull were eight loopholes, through which the soldiers could fire their rifles, making the Mark IX also the world's first Infantry Fighting Vehicle. Two of the loopholes were in the two oval side doors on each side. Despite using thinner (10 mm) armour plate, the weight was still 27 tons and the speed only 4 mph (7 km/h). The tank could also carry supplies in a tray on the roof behind the commander's armoured observation turret (being the highest point at 2.64 metres), while towing up to three loaded sledges. One of the first three was used as an armoured ambulance. After the end of the Great War the Mark IX's were used for some years. The type was named The Pig as the low front of the track looked like the snout of one.

C'est également aux Britanniques qu'échut l'initiative du développement de l'artillerie autopropulsée avec la mise en service du Gun Carrier Mark I armé d'un obusier de 60pdr en 1916-1917. À cette époque en effet, le major Gregg, un officier ingénieur travaillant pour le principal industriel impliqué dans la construction du Tank Mark I (Metropolitan, Carriage, Wagon and Finance) proposa la construction d'une mule mécanique utilisant des éléments du Mark I. La production d'un prototype fut approuvée dès le 5 juin 1916; l'étude commençant en juillet. Le premier prototype fut présenté au Tank Trials Day tenu à Oldbury le 3 mars 1917. Une commande de cinquante engins fut placée auprès des usines Kitson & Co. de Leeds et la livraison aux troupes débuta en juin pour se terminer le mois suivant. En dépit du réel succès de l'engin, celui-ci resta toutefois le seul de son genre sur les champs de bataille de la Première Guerre mondiale[note 5].

L'entre-deux-guerres (1919-1939)[modifier | modifier le code]

Despite the relative success of British tanks during WWI, Great Britain failed to successfully innovate in the field of armored warfare during the interwar period (1918-1939). There were three primary reasons for the British inability to capitalize on the tank's potential between the world wars: a failure to learn from the past, inadequate leadership, and a restrictive cultural climate[14].

During the interwar, a lot of development effort went into light tanks that would be useful primarily against infantry or for colonial police-type missions. The worldwide economic difficulties of the 1920s and 1930s led to an increased emphasis on light tanks also, since they were so much cheaper than medium or heavy tanks.

In the immediate aftermath of the First World War, Britain faced serious economic woes. Heavy defence cuts were consequently imposed by the British Government in the early 1920s as part of a reduction in public expenditure known as the "Geddes Axe" after Sir Eric Geddes.[15] The Government introduced the Ten Year Rule, stating its belief that Britain would not be involved in another major war for 10 years from the date of review. This ten-year rule was continually extended until it was abandoned in 1932.[15] The Royal Tank Corps (which later became the Royal Tank Regiment) was the only corps formed in World War I that survived the cuts. Corps such as the Machine Gun Corps were disbanded, their functions being taken by specialists within infantry units.[16] One new corps was the Royal Signals, formed in 1920 from within the Royal Engineers to take over the role of providing communications.[17]

Within the cavalry, sixteen regiments were amalgamated into eight, producing the "Fraction Cavalry"; units with unwieldy titles combining two regimental numbers. There was a substantial reduction in the number of infantry battalions and the size of the Territorial Force, which was renamed the Territorial Army. On 31 July 1922, the Army also lost six Irish regiments (5 infantry and 1 cavalry) on the creation of the Irish Free State.[18] Many Irishmen from the south nevertheless continued to join the British Army.

Until the early 1930s, the Army was effectively reduced to the role of imperial policeman, concentrated on responding to the small imperial conflicts that rose up across the Empire. It was unfortunate that certain of the officers who rose to high rank and positions of influence within the army during the 1930s, such as Archibald Armar Montgomery-Massingberd, were comparatively backward-looking.[19] This meant that trials such as the Experimental Mechanized Force of 1927-28 did not go as far as they might have.[20]

By the mid-1930s, Germany was controlled by Hitler's Nazi Party and was becoming increasingly aggressive and expansionist. Another war with Germany appeared certain. The Army was not properly prepared for such a war, lagging behind the technologically advanced and potentially much larger Heer of the German Wehrmacht. With each armed service vying for a share of the defence budget, the Army came last behind the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force in allocation of funds.[21]

During the years after the First World War, the Army's strategic concepts had stagnated. Whereas Germany, when it began rearming following Hitler's rise to power, eagerly embraced concepts of mechanised warfare as advocated by individuals such as Heinz Guderian, many high-ranking officers in Britain had little enthusiasm for armoured warfare, and the ideas of Basil Liddell Hart and J.F.C. Fuller were largely ignored.[22]

One step to which the Army was committed was the mechanisation of the cavalry, which had begun in 1929. This first proceeded at a slow pace, having little priority. By the mid-1930s, mechanisation in the British Army was gaining momentum and on 4 April 1939, with the mechanisation process nearing completion, the Royal Armoured Corps was formed to administer the cavalry regiments and Royal Tank Regiment (except for the Household Cavalry). The mechanisation process of the cavalry was finally completed in 1941 when the Royal Scots Greys abandoned their horses.[23]

Les théoriciens britanniques de la guerre moderne[modifier | modifier le code]

Following the war, development of mechanized forces was largely theoretical for some time, until many nations began rearming in the 1930s. The British Army had established an Experimental Mechanized Force in 1927 but failed to pursue this line due to budget constraints and the prior need to garrison the frontiers of the Empire.

In the aftermath of World War I, several theorists sought ways to avoid the indecisive nature of trench warfare, with its associated heavy casualties. One weapon which had shown promise was the tank. Colonel J. F. C. Fuller, formerly the Chief of Staff of the Tank Corps, proposed an all-tank force, which would operate independently against enemy headquarters and lines of communication. More moderate theorists such as the historian and former British Army officer Basil Henry Liddell Hart advocated mechanised forces of all arms, able to carry out operations of war other than the all-out offensive. A third influential reformer, Colonel Giffard LeQuesne Martel proposed that tanks should nevertheless be subordinated to infantry formations, while the large number of influential cavalry officers maintained that the horse still had a part to play on a modern battlefield, in spite of all evidence to the contrary on the Western Front in World War I.

Although some proponents of mobile warfare such as J.F.C. Fuller advocated "tank fleets", other soldiers such as Heinz Guderian in Germany, Adna R. Chaffee Jr. in the US and Mikhail Tukhachevsky in the Soviet Union recognized that tank units required close support from infantry and other arms, and that these supporting arms needed to maintain the same pace as the tanks[note 6].

Archibald Wavell : Wavell played a not insignificant role in the mechanization of the British Army. In 1926 Wavell became G.S.O. 1 of the 3rd Division, where « the most significant part of Wavell’s work . . . was his close association with the birth and early trials of the first mechanized [sic] formation in the world, the Experimental Armoured Force of 1927-8, which was the mother of all armoured divisions. » ( John Connell, Wavell: Scholar and Soldier (London: Collins, 1964), p. 155.). Wavell demonstrated his prescience and unorthodox thinking in the article « The Army and the Prophets » (R.U.S.I. Journal, 75 (November 1930): 665-675). Wavell addressed not only the potential of the air arm and gas weapons, but also addressed the transition to mechanized forces, « which do hold out some hopes of restoring to armies, freed from the dull obsession for mere numbers, full play for manoeuvre in the open field » (p. 668). In that same year Wavell was selected to command the 6th Infantry brigade of the 2nd Division, and in 1931 Wavell’s formation was entrusted with a series of experiments connected with the general mechanization of the Army, these experiments paralleling the earlier « Armoured force » experiments. Wavell, aptly described by General Burnett-Stuart as« that inspired and inspiring teacher of troops » also wrote Volume II of the Field Service Regulations (1935), a fact noted by Liddell Hart in his Memoirs (Volume I, p. 250). Wavell later successfully commanded the 2nd Division, and was Commander-in-Chief, Middle East (1939-1941), serving as O’Connor’s superior during the lauded Operation Compass[24].

La mécanisation de l'armée britannique : the first phase, 1918-1932[modifier | modifier le code]

From 1 April 1926, the 2nd Battalion, The King’s Royal Rifle Corps (2 KRRC) was chosen to carry out trials as the first mechanised battalion in the British Army. To quote from the 1931 KRRC Chronicle:

« "The Battalion was still organised in a similar manner to other infantry battalions on home service, namely, four rifle companies and a machine-gun platoon of 8 guns in the HQ wing. Early in 1927 a third section was added to the MG platoon, making 12 guns in all. On March 1st, 1928, the new infantry battalion organisation came into force, by which the fourth rifle company was abolished, and the MG platoon was formed into a MG company distinct from the HQ wing. At the same time the MG company was considered to contain four sections of 4 guns each when on war strength. … Soon after the change the first experimental MG company with Carden-Loyds was formed in the Battalion, although at the time these machines were driven [on attachment] by personnel of the Royal Tank Corps. The rest of the transport was driven by men of the Battalion." »

In 1929 the Battalion moved to Tidworth where the MG Company received its own Carden-Loyds driven by members of the Battalion. In the same year a mechanised anti-tank platoon was formed in HQ wing. The platoon consisted of two sections, each with two 0.5 inch Vickers anti-tank machine guns, carried in Carden-Loyds with trailers for the gun crew. In 1931 a mechanised mortar platoon of two sections carried in Carden-Loyds, each with two 3-inch Stokes mortars, was added[25].

- L' « Experimental Mechanized Force » (1927-1929)

The Experimental Mechanized Force was a brigade-sized formation of the British Army. It was officially formed on 27 August 1927, and was intended to investigate and develop the techniques and equipment required for armoured warfare. It was renamed the Experimental Armoured Force the following year. Over a period of two years, it participated in several exercises which proved the capabilities of mechanised forces against traditionally-organised and trained infantry and cavalry but also generated violent arguments within the Army. The Force was finally dispersed in February 1929.[26]

At the instigation of General George Milne, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the Secretary of State for War, Laming Worthington-Evans, decreed the formation of the Experimental Mechanized Force in October 1925. Milne was already inclined against the pure tank theorists, and organised the force as a balanced force of all arms, so far as resources allowed.[27] After the units concerned had completed their training on their new equipment, the Force officially came into existence at Tidworth on Salisbury Plain in August 1927.

Colonel Fuller had originally been considered for appointment as commander of the Force, but he turned it down, as it was combined with command of an infantry brigade and the administrative responsibilities connected with the garrison of Tidworth. The War Office refused to allot extra staff to assist him, and Fuller believed he would be unable to devote himself to the Force and its methods and tactics. Instead, Colonel R. J. Collins, whose professional background was light infantry, was appointed to command the Experimental Force.

The force was composed of:

- Flank Reconnaissance Group composed of the armoured cars of 3rd Battalion Royal Tank Corps (RTC)

- Main Reconnaissance Group equipped with Carden Loyd tankettes of 3rd Battalion RTC

- Battalion of the RTC, with 48 Vickers Medium Mark I tanks of the 5th Battalion RTC

- Mechanised Infantry Machine gun Battalion, supplied by the 2nd Battalion Somerset Light Infantry

- Mechanised Field Artillery Brigade (regiment) Royal Artillery, armed with 18 pounder guns and QF 4.5 inch Howitzers towed by a combination of Crossley-Kégresse half-tracks and Dragon tractors

- battery of self-propelled Birch Guns manned by 20 Battery, 9th Field Brigade, Royal Artillery

- Mechanised Light Battery, Royal Artillery, equipped with 3.7 inch Mountain Howitzers portéed on Burford-Kégresse half-tracks

- Mechanised Field Company of Royal Engineers[28]

Over the next two years, the Force participated in several exercises on Salisbury Plain, the traditional training area of the British Army, which was generally open with firm going, and therefore ideal for mechanised units. The Force's operations were almost invariably judged to be successful by the umpires. Its all-arms composition generally vindicated Liddell Hart's concepts, as the Force was able to undertake operations such as opposed river crossings which would have been impossible for an all-tank force. Nevertheless, Liddell Hart complained that the Force's operations were too small in scope and always served as an adjunct to larger, traditionally organised forces, rather than demonstrating that mechanised forces could operate independently and be strategically decisive.

Another shortcoming which the exercises highlighted was that the infantry's lorries could not keep up with the tanks on rough going.[27] The solution, which would be to provide the infantry with tracked or half-tracked armoured personnel carriers, was too expensive. After the disbanding of the Experimental Armoured Force, the British Army formed ad-hoc armoured forces in which the Tank brigades and Motorized Infantry brigades tended to operate independently of each other, a fault repeated in the early years of World War II[note 7]

- Mécanisation de la cavalerie

The mechanization of the British cavalry was retarded because of the cavalry’s irrational attachment to their horses. In the 1920s, because of the mechanical shortcomings of armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs), there were still some tasks that horsed cavalry could perform better than tanks or armoured cars. The decision to mechanize the regular cavalry was delayed until the mid-1930s not merely because of a shortage of the funds to purchase sufficient AFVs. It was delayed because it was not until then that even half-satisfactory vehicles were ready[29]. The first cavalry regiment to « mechanise » was the 11th Hussars in 1928, the last one beeing the Royal Scots Greys in 1941.

The 1930s[modifier | modifier le code]

Les matériels[modifier | modifier le code]

New equipments were tested mainly by the Mechanical Warfare Experimental Establishment (later called the Mechanisation Experimental Establishment).

In 1919 the British Army found itself with an acute shortage of armoured cars as many wartime vehicles were worn out. The Austin Motor Company of Birmingham agreed to manufacture armoured bodies based on the wartime armoured cars that they had built for the Imperial Russian Government, provided that the War Office could provide suitable chassis. These ‘Russian’ cars had twin side by side turrets. Some had served with the British Army’s Tank Corps. The War Office had a large number of American-made Peerless 2½-ton trucks in store and agreed to supply 100 chassis to Austin. The Peerless was a robust vehicle with a chain-driven rear axle and the British used large numbers in World War I. It was too long for the Austin bodies so that rather a lot of the chassis poked out at the back. It was the first armoured car to have the driving controls duplicated in the rear of the vehicle so that it could be driven in reverse to get out of ‘tight corners’. The resulting hybrid wasn’t a very good armoured car. It was too big, unwieldy and slow (six tonnes, 48-hp engine, 18 mph top speed, two .303-inch machine-guns) and the crew of four got a rough ride on solid tyres. Some of the Peerless cars were sent to Ireland in 1920 although the superior Rolls Royce armoured car quickly replaced them by the end of 1921. Some were passed on to the National Army of the Irish Free State and remained in service until 1934 by which time the chassis were worn out. The bodies and guns were reused on locally-manufactured vehicles. Peerless armoured cars were also used in Britain to escort food convoys during the General Strike of 1926. When they were withdrawn from front-line service they were issued to the Royal Tank Corps' Territorial Armoured Car Companies; one lasted with the Derbyshire Yeomanry until May 1940 when it was relegated to airfield defence.

The Tankettes were a type of small armoured fighting vehicle resembling a tank, intended for infantry support or reconnaissance. Tankettes were designed and built by several nations at that time. The concept was later abandoned due to limited usefulness and vulnerability to antitank weapons, and the role of tankettes was largely taken over by armoured cars. A famous British Tankette design were the Carden-Loyd tankettes, a series of British pre-World War II tankettes, with the most succesfull Mark VI tankette, the only one built in significant number. Not so much a light tank as a tracked machine gun transporter, the Carden-Loyd tankette was nevertheless an important development in armoured fighting vehicles in the Inter-war period.

The Artillery Regiment of the brigade held a battery of Birch guns. The Birch Gun was the world's first really practical self-propelled artillery gun, built at the Woolwich Arsenal in 1925. The gun was never highly regarded by the British High Command, purely for prejudicial beliefs and political pressure rather than any real lack of ability. Named after General Sir Noel Birch, who was Master General of Ordnance at the time, the Birch gun had real potential. It was built upon a Vickers medium tank chassis and mated originally with an 83.8 mm then with a 75 mm field gun. The project was abandoned in 1928 after political pressure killed off any plans to complete the third version of this weapon. The armament for the original Birch Gun consisted of a 83.8 mm (3.3 inch) field gun, later changed to the 75 mm gun on the Birch gun Mk II and from then on was able to be fired either at ground targets or in the air-defence role, being given a much higher rate of elevation to be fired at enemy aircraft.

L'arme blindée britannique dans l'entre-deux-guerres[modifier | modifier le code]

Following the Great War, many experiments involving armoured vehicles were conducted in the United Kingdom. Particularly many advances were made in the areas of suspensions, tracks, communications, and the organization of these vehicles on the battlefield.

Britain continued its technical dominance of tank design from 1915 through at least the early 1930s. British designs, particularly those from Vickers-Armstrong, formed the basis for many of the most common tanks of the 1930s and early WWII. For example, the Vickers Six Ton Tank was the basis for the Polish 7TP, the Soviet T-26, and was a major influence on the Italian M-11 and M-13 series and the Czech LT-35. Ironically, the six-tonner, which was arguably the most influential design of the late 1920s, was not adopted by the British Army.

Another notable design was the Vickers Medium Mk II, a pivotal design which combined some of the best traits of WWI tanks into a much faster tank. It had a fully rotating turret on top like the FT, but mounted a dual-use 3-pounder gun (that could fire both high-explosive and anti-tank shells) with a coaxial machine gun. It also had a radio, a machine-gunner position in the front of the hull, and some limited use of sloped armour. Some of these tanks would go on to serve in WWII, though most of the significance of the design lies in the amount of features that were copied (or at least also used) in later tank designs.

A perhaps less significant but also notable design was the Vickers A1E1 Independent, which was a large heavy tank that was built in 1925. It had a large main turret and four smaller turrets. This design concept was later used by the Soviet T-28 and T-35 tanks as well as the German Neubaufahrzeug.

Exponents of the replacement of the cavalry function by armoured vehicles were Liddell Hart and Fuller. Their opponents misinterpreted (either mistakenly or deliberately) them as proponents of an all-tank fighting force, though their views did specify that artillery and infantry should be mechanised to make them as fast and manoeuvrable as the tanks they advocated, and experiments were curtailed.

Eventually, by the 1930s, British experiments and their strategic situation led to a tank development programme with three main types of tank: light, cruiser, and infantry. The Infantry tanks were tasked with the support of dismounted infantry. The maximum speed requirement matched the walking pace of a rifleman, and the armor on these tanks was expected to be heavy enough to provide immunity to towed anti-tank guns. Armament had to be sufficient to suppress or destroy enemy machine gun positions and bunkers. Cruiser tanks were tasked with the traditional cavalry roles of pursuit and exploitation, working relatively independently of the infantry. This led to cruiser tank designs having great speed. To achieve this they were lightly armoured, and tended to carry anti-tank armament. The light tanks were tasked with reconnaissance and constabulary-type colonial roles, with cheapness the major design factor. The British doctrine led to a neglect of firepower[note 8].

La situation en 1939[modifier | modifier le code]

After the Munich Crisis in 1938, a serious effort was undertaken to expand the Army, including the doubling in size of the Territorial Army, helped by the reintroduction of conscription in April 1939.[30] By mid-1939 the Army consisted of 230,000 Regulars and 453,000 Territorials and Reservists.[31] Most Territorial formations were understrength and badly equipped. Even this army was dwarfed, yet again, by its continental counterparts. Just before the war broke out, a new British Expeditionary Force was formed.[32] By the end of the year, over 1 million had been conscripted into the Army. Conscription was administered on a better planned basis than in the First World War. People in certain reserved occupations, such as dockers and miners, were exempt from being called up as their skills and labour were necessary for the war effort.[33]

Between 1938 and 1939, with the a substantial expansion in the Army, a number of new organisations were formed, including the Auxiliary Territorial Service for women in September 1938; its duties were vast, and helped release men for front-line service.[34]

The pre-war British Army was trained and equipped to be a small mechanized professional army however its main function was to garrison the British Empire and as became evident during the very first weeks of the conflict was woefully unprepared and ill-equipped for a war against a modern army.

Full mechanisation of the British Army was undertaken in the 1930s and in 1939, Britain has the only all mechanised Army, The British forces having that way the advantage of a fully motorised system of troop movement. This enabled relatively fast deployment of forces. Even the Germans hadn't managed to completly mechanise, and only a few units were fully mechanised.

However the armed vehicles of the British army at the time do not compare particularly favorably with those of their opponents. Tanks such as the Matilda II were difficult to destroy but lacked the maneuverability to engage in rapid attacks and adequate armament. The first Valentine tanks were delivered in May 1940.

- L'arme blindée.

La « Mobile Division »

- Infanterie et artillerie.

Débuts de la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1939 - 1941)[modifier | modifier le code]

La « British Expeditionnary Force » de septembre 1939 à l'« Opération Dynamo »[modifier | modifier le code]

The whole of the BEF was mechanised, and the majority of those left at home. The British Army was the most mechanised of all the combatants in the Battle Of France.

Balkans et Afrique du Nord en 1941[modifier | modifier le code]

Crise et reconstruction[modifier | modifier le code]

The British Army only had 100 tanks left after Dunkirk and Vauxhall Motors were under instructions to produce the tanks as quickly as possible.

-

Mk VIC knocked out during an engagement on 27 May 1940 in the Somme sector.

-

« Beaverette »

- Les matériels américains.

Articles connexes[modifier | modifier le code]

Liens externes[modifier | modifier le code]

- (en) 1920s-1930s: Mechanisation and the « British way in warfare » , Royal United Services Institute.

- (en) British Mechanized Doctrine during the Inter-War Period

- (en) Archives 1940 sur YouTube

- (en) Tankettes et Carriers dans l'armée britannique

- (en) British Military History : United Kingdom 1930 - 1938

- (en) British armoured cars

- (en) London Transport Museum : World War One Gallery

- (en) Landships site de documentation consacré aux matériels de la Grande Guerre.

Bibliographie[modifier | modifier le code]

Bibliographie en anglais[modifier | modifier le code]

- (en) Robert H. Larson : The British Army and the Theory of Armored Warfare, 1918-1940, University of Delaware Press, Newark 1984.

- (en) David Fletcher, Moving the Guns: the Mechanisation of the Royal Artillery, 1854-1939, HMSO, (ISBN 0112904777)

- (en) David French, Raising Churchill's army: the British army and the war against Germany, 1919-1945, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 9780198206415) (extraits)

- (en) J.P. Harris, Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903-39, Manchester University Press, (ISBN 978-0719048142)

- (en) Steve Madden & Chris Orchard : British Forces Motorcycles 1925-45, Sutton Publishing Ltd 2006 (ISBN 9780750944519)

- (en) Collectif : The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean, The West Point Military History Series, Square One Publishers 2002.

Bibliographie en français[modifier | modifier le code]

Autres[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes et références[modifier | modifier le code]

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

- Cette section est partiellement issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Motor War Car » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Cette section est partiellement issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Mechanized infantry » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Cette section est partiellement issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Mechanized infantry » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- voir son roman intitulé The Land Ironclads de 1904

- Voir l'article sur Wikipedia en anglais consacré à cet engin.

- Cette section est partiellement issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Mechanized infantry » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Cette section est issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Experimental Mechanized Force » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- Cette section est partiellement issue de la traduction de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Tanks of the interwar period-United Kingdom » (voir la liste des auteurs).

Références[modifier | modifier le code]

- Robert H. Larson : The British Army and the Theory of Armored Warfare, 1918-1940 : présentation et synthèse.

- Idem

- Référence

- Lord Montagu and David Burgess-Wise Daimler Century ; Stephens 1995 (ISBN 1 85260 494 8)

- (en) Kenneth Macksey, The Guinness Book of Tank Facts and Feats, Guinness Superlatives Limited, , 256 p. (ISBN 0851122043)

- (en) Spencer Tucker, The European Powers in the First World War, Routledge, , 816 p. (ISBN 081533351X, lire en ligne)

- Armoured Fighting Vehicules of the World, Duncan, p.3

- Popular Mechanics, sept. 1912.]

- Vue d'artiste

- [http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/FWWlorry.htm Référence.

- (en) Jack Livesey, Armoured Fighting Vehicles of Would Wars I and II, Southwater, (ISBN 9781844763702), p. 84

- « Exploring 20th Century London - Buses », Museum of London (consulté le )

- « Ole Bill Bus », Imperial War Museum (consulté le )

- A.C. Writer :British Armored Warfare Innovation in the Interwar Period,Yahoo Mobile Associatedcontent, July 18th, 2007.

- Mallinson, p. 322

- Stevens, F.A., The Machine Gun Corps : a short history. Tonbridge : F.A. Stevens, 1981.

- Royal Corps of Signals - Heritage

- Irish Regiments in World War I

- Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, Murray, Williamson & Millett, Allen R., Cambridge University Press (1996), (ISBN 978-0521637602)

- Technology, Doctrine and Debate: The evolution of British Army Doctrine between the Wars p. 29 Canadian Army Journal, Vol. 7.1, Spring 2004

- Mallinson, p. 330

- Mallinson, p. 327

- Grant and Youens, p. 34

- Référence.

- The Royal Green Jackets (Rifles) Museum.

- HMSO 1990, p. 58.

- French, p.29

- HMSO 1990, p. 58.

- David French : The Mechanization of the British Cavalry between the World Wars in War In History Journal, July 2003 vol. 10 no. 3 pp. 296-320.

- Mallinson, p. 331

- The War, Day by Day Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1939

- Mallinson, p. 335

- Fact file: Reserved Occupations BBC

- Auxiliary Territorial Service in the Second World War Imperial War Museum