Utilisateur:C as Charisma/Brouillon

Charisma, from Greek “Kharis” or “Gift of Grace” is a concept that refers to compelling charm and attractiveness that induces enthusiasm and even devotion.[1] While applicable in all spheres of the social sciences, in politics Charisma refers to extraordinary leadership abilities inspiring emotional reactions through the use of symbols. The concept as a political occurrence was popularised by Max Weber and his exploration of the concept as a type of legitimacy.

Not to be mistaken for a personal trait, the legitimacy that results from such qualities also depends on the interaction between the leader and his subjects. The nuance lies in the perception of these abilities in the group of people led, without the favorable opinion of which the individual characteristics of a leader would not amount to much. Weber himself placed Charisma alongside Tradition and Reason as three “principles of obedience”[2], carried respectively by “prophets”, “elders” and “organisers” to ensure legitimacy. This classification is indicative of the importance of charisma in leadership in that it frames it as a pillar of political authority. However, recent examples of politicians galvanising the masses and pushing the limits of common sense, along with the traumatic collective memory of less recent ones, opposed to quieter successful figures characterised by bureaucratic efficiency rather than personal attractiveness raise questions. What is the real importance of charisma if legitimacy can be achieved by other means? Is charisma enough? Is it necessary? A synthesis of the spirit behind these interrogations; “Is Charisma a Condition for Effective Political Leadership?” will guide this entry.

The first logical step to approach the topic would be to lay down the theoretical basis of the concept of charismatic leadership. Ranging from the Greek origins of the concept to the works of Weber, of Tucker, and others, the definition of Charisma will be established in detail. Critical elements will be implemented to underline some limitations of the concept, notably the overuse of the term in contemporary academic research, in order to establish the first parts of an answer.

The second step will be to take the factor of time into consideration as charisma, like all objects and concepts, is conditional to time, and is not fixed indefinitely. The relationship with time may take the form of charismatic legitimacy as the product of a certain time period and its context, the importance of crisis in the formation of this charismatic identity, without which it tends to falter, and finally the relationship with the inevitability of death which raises considerations of perpetuation, mythologising and succession.

The last part will nuance further by reconsidering the usage of charisma in contemporary politics and understand it through the prism of today’s democracy. Most importantly, it will examine the relationship between institutions, democracy, liberalism, rationality, legality and charismatic leadership to determine whether they are compatible, and how they would function alongside or even within one another, considering if a possible democratic charisma exist or not.

(Victor Wauters, Vasco Queiro, Salim Ouaritini)

The charismatic legitimacy : its origins and evolutions (Vasco)[modifier | modifier le code]

Charismatic authority has been a popular topic in the study of political sciences ever since its formulation by sociologist Max Weber in the early 20th century. Its relevance and usefulness in the field of study of political sciences and political analysis has, however, been extensively contested amongst scholars. Is charismatic authority a legitimate field of study in political sciences? This first part of the handbook will attempt to answer this question by first outlining the word’s etymology and history, followed by some background on Max Weber theories regarding the concept. I will then analyze some of the criticisms academics have had against Weber’s theory. Finally, I will show how charismatic authority can still be useful to political sciences and empirical research by creating an ‘index of charismaticness’.

The origins of Charisma: from ancient Greeks to Weber[modifier | modifier le code]

The etymology of the word charisma gives some insight into its present-day definition. The word is derived from the ancient Greek word Kharisma, which signifies a gift from God. It was meant as a talent, gifted by God upon a mortal (such as, for example, being able to tell the future). The term can later be found in both the Bible and the Torah[3]. Up until the 19th century, the concept of charisma was still reserved for religious figures such as popes or priests, who were ‘endowed’ with God-given talent. German sociologist Max Weber secularized the term, rendering it applicable to politics. Charisma was no longer a God-given gift, but rather, a characteristic of certain leaders that could be studied and analyzed through the academic lens of sociology, psychology, or political sciences.

Max Weber first outlined his ideas on charisma in his 1922 book Economy and Society.[4] The majority of Weber’s work on charisma surrounds the idea of political legitimacy. Charisma, according to him, was one of three types of legitimate rule. There is traditional authority, such as feudalism or monarchies, whose political legitimacy stems from traditions or customs. Then there is rational-legal authority, such as bureaucracy and many regimes in modern democracies, whose legitimacy derives from clearly established laws. Finally, there is charismatic authority.

Charismatic authority is, according to Weber, an authority that is derived from the relationship between a leader and his followers. The leader in this type of authority tends to possess extraordinary qualities, which manages to rally followers, who then freely accept the leader’s authority due to these qualities. These followers do so “voluntarily, and without the thought of material recompense”. The followers tend to display absolute obedience and an unshakable trust towards their leader. The important aspect of this type of authority is the perception of extraordinariness by the followers, as the validity of charisma stems from the followers’ belief in it. This extraordinariness has to be frequently reinforced in order to furnish ‘proof’ of charisma, making this a particularly unstable and often ephemeral type of authority.

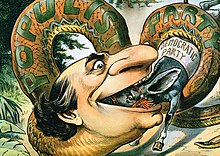

A distinction between charismatic authority and the other two types of authority is its innovative, and sometimes even revolutionary, character. While traditional authority relies on the past and rational authority relies on established laws, charismatic authority marks a rupture with the status quo. Charismatic authority requisites some type of movement. Without the notion of movement, a charismatic leader would simply be an idolized leader. A charismatic leader is idolized, but also manages to use this popularity to summon people to join a movement for change. The notions of a charismatic leader and a charismatic movement are inextricable. A charismatic leader can found a movement, making the movement charismatic from the outset (such as Hitler and German National Socialism), but a movement can also become charismatic thanks to the introduction of a charismatic leader (such as the Russian Marxist revolutionary movement and Lenin). Charismatic authority can cover a large spectrum of movement, ranging from fascist, to communist, to democratic, etc.

If a charismatic leader is defined by their ability to get supporters to back a particular movement, and their legitimacy stems from this support, then the metric for measuring whether or not a leader is charismatic should stand in their ability to gain a following that backs a charismatic movement. Oftentimes leaders are described as ‘charismatic’ once they’re already in power. This is due to the fact that power can often bring about phenomena that are similar to those that charisma would, such as revolutionary change. Stalin was not a charismatic leader, yet due to his position in power, brought about extensive change in the Soviet Union. It is important to analyze these leaders before they become powerful, as a charismatic leader will manifest their charisma before they rise to power.

Another distinctive aspect of charismatic authority is, according to Weber, the time at which they come to power. He believed that the complete devotion accorded to the charismatic leader by his followers stems from distress. It is in times of ‘psychic, physical, economic, ethical, religious, political distress’ that a charismatic leader has the opportunity to rise to power. The more distressed a population is, the more likely a charismatic leader is to garner masses of supporters, and to gain power. Movements for change are always most popular in distressing times, as people search for an escape from their sorry predicaments. Charismatic leaders propose a salvation from the people’s distress and are therefore perceived by their followers as a type of savior. Academic Robert Tucker states in his analyses of charismatic authority that “Charismatic leadership is specifically salvationist or messianic in nature”[5]. This explains why charismatic leaders’ followers are often so illogically and enthusiastically devoted to them. This helpless devotion to the leader is also what makes this type of authority unstable, however, as without periodic proof of the leader’s efficacy in solving their people’s predicament, their following will crumble, and therefore so will their legitimacy and charismatic façade.

What qualifies a charismatic leader? This is where most of the critique’s against Weber’s works on charisma stem from, as he is decried by many to be unclear and ‘fuzzy’ regarding this point. A charismatic leader could possess extraordinary skills of communication, that manages to ‘sell’ a vision in an effective and convincing manner. Conversely, a charismatic leader could have the practical skills to effectively implement change. In either case, it is extraordinariness, or the perception of extraordinariness, that is the key feature of charismatic leadership.

A Critique of Charisma[modifier | modifier le code]

Ever since Weber’s theory, the usage of the word Charisma has seeped from the fields of academia into everyday parlance. The term has become ambiguous, with various connotations and interpretations. The adjective is now used to denote any type of leader with even remote ‘charming’ or ‘inspirational’ characteristics. Barack Obama, Justin Trudeau, Emanuel Macron, have all been labelled by the press at some time or another as ‘charismatic leaders’[6]. Academic Philip Smith found that the word had become “a debased, floating signifier”[7]. This indiscriminate use of the word has turned it devoid of any true substance, both in everyday speech and especially within the fields of political academia.

Furthermore, many academics find that Weber’s theory of charismatic authority is itself vague and inconsistent. Philip Smith described Weber’s work on charisma as ‘suggestive, elusive, brilliant, and fragmentary[7]. Weber doesn’t provide a clear framework for measuring ‘charismaticness’, rather providing vague references to traits and characteristics that a charismatic leader, or the society in which a charismatic leader could rise to power, possesses. Weber himself became skeptical regarding the concept, and in his later works diminished its significance[8].

This indefiniteness surrounding its definition and characteristics has rendered it, in the eyes of many academics, useless within the fields of political science research, and several have proposed dropping it entirely from their field of study. Political theorist Arthur Schweitzer declared it useless for empirical research[9], and academic Carl Friederich found it to be of ‘minor importance’ in the field of study[10]. Academic William Spinrad advocated for its entire elimination from the field of political analyses[11]

Creating an index of ‘Charismaticness’[modifier | modifier le code]

The concept of charismatic authority can, however, be a useful and relevant concept in political sciences and analysis. Rendering the concept of charismatic leadership clear enough for political sciences and eventual empirical research, however, requires modifications and clarifications to Weber’s theories. Firstly, Using political legitimacy as the typology for charismatic leadership isn’t necessarily the best way to develop that theory, and it isn’t operational enough for further research and analysis. It delimits the concept. Secondly, a clear definition, derived from Weber’s theories, has to be created as a groundwork in order to further analyze the concept. Finally, a criterion of ‘charismatic-ness’ has to be set based on this definition, in order to set a standard, and so that empirical research can be feasible.

To form a clear definition of charismatic authority, one must use the central components of his theories regarding the concept. Using these theories, one can decipher that, at its core, charismatic authority is a legitimate authority that is inherently personal (rather than impersonal, which is typical to rational forms of authority), and that has as an aim the alteration of some type of status quo.

Now that we have this simple yet clear definition of charismatic authority, one has to break down its characteristics. The two characteristics of political authority based on this definition are 1. how personal it is and 2. its degree of radicalism. Based on these characteristic, one can build a criterion, or ‘index of charismaticness’, in order to potentially conduct empirical research. Political researcher Takis S. Pappas, in his work named Political Charisma Revisited, and Reclaimed for Political Sciences[8], breaks down the empirical testable that can be used to measure whether a leader is ‘charismatic’ or not.

According to Pappas, the ‘personal’ aspect of charismatic authority can be broken down into two criteria that can easily be measured, and that therefore can be used in the field of empirical research. The first of these is the centralized control of the charismatic leader. Charismatic authority is defined by the unregulated and oftentimes absolute power that the charismatic leader holds within his group/party/organization. Most if not all charismatic leaders of the 20th century (Hitler, Mussolini, Gandhi, Lenin, etc.) held absolute power over their respective groups. The second attribute of charismatic authority is the emotion and passion shared between the charismatic leader and his followers. As previously outlined in Weber theories, the relationship between a charismatic leader and his followers is based on emotions and sentiment, rather than sensibility and rationality. Political theorist Schweitzer named this phenomenon in charismatic authority the “emotional seizure of the masses”[12].

Pappas then identifies two empirical criteria regarding the radical aspect of charismatic authority. The first of these is the overhaul of an existing system of authority, and the second is the institution of a new system. Charismatic authority will typically provide new foundations for society, be it symbols, or national narratives.

Using the criteria identified by Pappas, the concept of Charisma can now be used in political science research for empirical data.

In conclusion, Weber secularized the ancient concept of charisma, rendering it applicable to the sphere of political sciences. His theories on charisma are, however, too vague and limiting to properly conduct academic research based on the concept. Furthermore, the overuse of the word both in academic and everyday speech has rendered it devoid of any substance and clear meaning. The concept of charismatic authority can still, however, be relevant and useful to political sciences, by forming a clear criterion of ‘charismaticness’, on which to base potential empirical research upon. This ‘charismaticness’ index should be based on: how centralized and absolute a charismatic leader’s power is within his group; the emotion and passion shared between the charismatic leader and his followers; whether they have (or are attempting to) overhaul of an existing system of authority; and finally the institution (or attempted institution) of a new system. By using this index, the concept of charismatic authority can be both relevant to comparative politics, and applicable to empirical research.

Rise and Fall of Charismatic Legitimacy - A Timeless or Time-bound Quality? (Victor)[modifier | modifier le code]

The Sporadic Nature of Charisma as a Social Fact[modifier | modifier le code]

While it has been made clear that charisma is a potential vector of leadership, it is not unconditional and more importantly it is not intemporal. This is precisely why the idea of time is a pertinent prism of analysis with regards to the level of charismatic stability, which nuances the conception of charisma as a requirement for leadership. Much has been made of Weber’s theories and the emphasis on the emotions, even emotional seizure,[13] provoked by the so-called Gift of Grace[14] which leads to an almost religious following. Political passions, resentment and even ecstasy sometimes described as organistic intoxication in its extreme forms,[14] are all products of charismatic rhetoric. However, understanding the temporality of such leadership allows a more nuanced understanding of the commonly accepted Theory.

As explained, charismatic legitimacy, more than just a personal reality, is the social fact of the interaction between an emitter and recipients. Just like any social interaction, its outcome depends on both parties and thus implies a degree of compromise. In this sense, the acceptance of charismatic authority also depends on the collective psyche of the followers, whose condition may not be optimal for the rise of leaders.[14] The study of individual cases of charisma therefore needs to be accompanied by an examination of the factors that construct the population’s reception of the leader, as charisma is malleable and context-sensitive. [15]Hence the determinant weight of leaders’ political choices and the emphasis by Schweitzer on the link between politics, ideology and emotion. This reflection frames the emergence of charisma as a fruit of its situation,[16] as the development of the collective state of mind of a society is independent from the leader’s personal one, yet, as explained, charisma finds its roots in a favorable synthesis of both. The example of Lenin who while now considered an example of charisma was propelled in the role of Chairman of the USSR by the conditions of his time and the necessity for revolutionary discourse, despite elements of death positivity bias[17] which will be addressed later, highlights exactly this relationship between personal characteristics and national trends within societies responding to charismatic stimulus.

According to Weber, the pinnacle of charismatic leadership occurs while the driving mission of the leader in question is in Statu Nascendi[16], or in the process of being born and put in place. That is to say there is a periodisation of the rise and fall of a charismatic dynamic, which justifies this insistence on the concept of time, or at least the repartition of times. The example of Charles de Gaulle is particularly telling in uncovering this reality; the tipping point of his downfall is often directly linked to the referendum for the renovation of the Senate in 1969, described by a Francois Mauriac as an “unprecedented case of suicide in the midst of happiness”[18] which severely damaged his image in the eyes of the French, and the visible disconnect between the insistence of the strongman figure in the context of national liberation, and the emancipatory waves of 1968 that he struggled to get in touch with, which marked the context of the referendum.[19]

It is claimed that charisma has been excessively investigated with regards to complex historical occurrences,[20] with recurring examples being the rise of Nazism and Bolshevism, with such interpretation being a case of reductionism and a heuristic to simplify discourse as an alternative to thorough historical research.[20] Indeed, if according to Weber, legitimacy in charisma is conditioned by the ability to deliver and end product, the notion of efficacy and the need to display proofs of courage and will,[13] then as shown by the example of military leaders depending on the success of their campaign,[11] charismatic legitimacy evolves. As demonstrated by Schweitzer through the example of Arthur McCarthy, who was able to garner support and stimulate emotional responses to fears of communist and homosexual subversion in the context of the cold war, before being censored and losing support following outrage[21], the supernatural abilities of charismatic leaders may be linked to special circumstances and may not be transferable to others.[9] Thus, inadequacies may lead to the perception of charisma to falter over time, especially in times of difficulty.

Crisis - Genesis of Charismatic Authority[modifier | modifier le code]

To push our reasoning further, in the words of Weber “All charisma [...], at every hour of its existence, and always increasingly as hours pass, tends to experience a slow death, choking under the pressure of material interests, after having lived, in the storm of emotions, a life stranger to economics.”[16]The storm of emotions, here, is understood as times of crisis and the distress, resentment, fear and passions they may create. In other words, hardship is the central factor of adherence to charismatic authority, as only it can divert collective sentiment to an extent such that economic realities are pushed to the sidelines, again stressing the weight of spatio-temporal realities in the infatuation with charismatic figures. When established procedures fail, institutional organisation is disturbed and the foundations of the system are shaken,[22] calling for a radical transformation, in the words of Weber, which arises from conflict, suffering or enthusiasm, distress and enthusiasm, collective excitement, extraordinary events.[23] To try to explain these phenomena, it is important to consider the dynamics operating on a societal level. In times of crisis, collective fears and anxieties may be such that only a socially gifted charismatic leader will have the necessary vision to gain trust and thus legitimacy, in the sense that they will be able to challenge the status quo and communicate inspiration for the future.[9] However, as the situation evolves and the needs of societies follow, these emotions dissipate. The moment is gone, emotions falter away, and new considerations emerge, of less radical nature. To highlight the time bound nature of this sort of situation, these events may also be seen through micro-situations of crisis, like a riot for example.[9] The immediate stimulus which creates the resentment or enthusiasm necessary to incite a group to violent acts of vandalism, is only short-lived before reason takes over again.

This radical transformation can be applied, on a less immediate scale to many leaders seen as charismatic, the most documented of which would be the likes of fascist leaders like Hitler and Mussolini, who’s self proclamation of alternative leadership in times of crisis strengthened their claim to charisma.[11] Indeed, the inter-war international order and its unstable nature favored such anti-establishment rhetoric in the same way that the context of the process of decolonisation was fertile for the rise of figures like Nkrumah in Ghana or Nasser in Egypt[11] who’s image dissipated after the evolution of the socio-political context. In fact Hobbesian natural law[24], itself recurring subject of Weberian analysis,[25] may re-emerge in dilute forms in times of crisis, thus the role of the charismatic leader to restore order through a charismatic approach, before the considerations change and the mandate of their Social Contract is no longer applicable and their support fades, which is Nasser’s distancing from Pan-Arabism is sometimes interpreted as an example of.

Beyond the idea of historic breaking points as fertile for charismatic leadership, another angle is charismatic leadership as the antidote to revolutionary self-destruction[9], or the risks represented by taking up arms to defend the movement, leading in an inevitable physical confrontation against institutions, and thus their downfall. The faith in a leader may lead the movement to transcend these historical ruptures, which leads us to our next part, investigating the surpassing of the individual figure in vehicling charismatic authority post death.

Death - The Mythology of Charisma[modifier | modifier le code]

As we have already touched upon, the distinction between the ideological appeal of a revolutionary movement and the subsequent active creation of a mythology around it is primordial. In the same way, it is vital to keep in touch with the historical distortions brought forward by the tendency to venerate characters after their death, like the aforementioned example of post-mortem deification of Lenin. As explained by Nye, charismatic leadership is a circular phenomenon better observed after death.[26] While, in light of the research brought forward, this observation can be questioned, as there are plenty of examples of very visible charisma during the lifetime of leaders and of movements and veneration completely vanishing after their passing, it does touch upon the importance of death in the narrative surrounding leadership and legitimacy. In collective consciousness this can be translated in a sense of personal connection linked to martyrdom. Leaders who are more prototypical of a specific group tend to be seen as more charismatic than leaders who were less closely related. In this sense Charisma may increase post-mortem because people regard the dead through their significance to society and see their fate as overlapping with the fate of the social group that they represented,[15] should this be exemplified through Martin Luther King or John Fitzegrald Kennedy[11], to only mention two.

In another aspect of the question, the example of Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is sometimes used to justify the notion that the evolution of the perceptions of national priorities will not always negatively affect the following by the subjects, and even less so after death. The emphasis on timeless symbols representing the leader’s mission and his memory contribute to the construction of a Death Positivity Bias, that is to say the observed trend whereby citizens tend to consider the leader more virtuous morally after their death than during their lifetime, and attach themselves more easily with the movement and the mission he embodied. The consequence of this warping of memory would be to ensure the survival of the movement, cementing it as a durable political project in which future politicians would be active and who's following would stay loyal.[17] Indeed, if the immediate consideration of the Venezuelan public changed, so too did Chavez’s concrete political line despite the maintenance of official discourse. While the anti-imperialist rhetoric, the insistence on maintaining close contact with the population and social conscience, economic policies such as cutting state budget by as much as 7%, strengthening the Investment Fund for Macroeconomic Stabilization showed a swerve away from the socialist core of his rhetoric. Furthermore, the poor economic management, which led to the failure to latch on to booming oil prices in the early 2000, combined with unsuccessful protectionist policies could have suggested a disaster for public opinion. Yet, through the emphasis on symbolic elements, the idea of proximity to the people and undeniable oratory qualities which would fit Weberian supernatural qualities, public appraisal was not significantly touched. We can therefore talk of attachment not to the integrity of policies but rather to the persona. This is even more relevant when observed after his death. It has been suggested that Bolivarianismo is fading. While the public approval rate of Nicolas Maduro, only 15% in 2019 does justice to the unpopularity he begets, the same poll reveals about 30%[17] feel strongly attached to Hugo Chavez and the movement, a similar number to the polls in 2012 at the time of his death, near the peak. Maduro, perhaps by lack of charisma is rejected, despite proclaiming himself son of Chavez and trying to impose continuity.

Perhaps a common schema, represented by the example of Bolivarianismo exists, or at least a model that could be applied to various situations, linked to Weber’s concept of routinisation of charisma.[17] While the creation of the myth around the leader during times of need instils the acute conception of legitimacy in collective consciousness, the question of perpetuation is raised. This is precisely where the analysis Andrews Lee[17] falters regarding the insistence on the endurance of the Bolivarian regime, and where Weber’s routinisation and Spinrad’s distrust towards the prism of charisma become relevant.

Routinisation implies the institutionalisation or rationalisation of Charisma. After the death of a leader, it also suggests the construction of a charismatic structure, sometimes beyond the individual to enable the spirit to live on, yet this process would degrade the charismatic nature of the leadership system in place, which gets lost in the impersonal ties it creates.[16] Indeed, if there is an effort to mythologise around the character of the dead leader, it is precisely because the sacred character of charismatic rule is lost. In this case, and paradoxically, given the historic opposition between these two trends, the interlinkage with traditional legitimacy is difficult to avoid. Thus the denaturation of charismatic leadership.[16]

Of course this will not always be the case, and often it depends on the methods of succession. while in some cases the demise after death will occur before Routinisation can even take place, as it happened with Buddha’s death and the subsequent disappearance of Southern Buddhism in India due to the movement’s amorphism and lack of direction.[16] In other cases the issue of succession led to violent divisions like it did with Islam. In other cases, the issue of death and martyrdom were warped to avoid such questions as it was with the resuscitation of Jesus or the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. The last two examples link back to the original works of Weber on the role of divine qualities of charisma in religious history, yet this also poses further questions on the precise role of charisma in politics and bureaucratised systems, upon which the shadow of Routinisation looms.

Charisma and democracy: A dangerous liaison? Understanding Charisma in contemporary democracies (Salim)[modifier | modifier le code]

Reconsidering charisma in today’s liberal democracies:[modifier | modifier le code]

As charisma has been considered as a time-bound property, it may be interesting to study its meaning as well as its role in our time: the time of rising or established liberal democracies in the digital era. The term "charisma," which was once primarily used in the context of Christian church organization, has now become a common term for commenting on the political life of democracies.[27] “Clearly, after Weber, there has been a decisive and irreversible semantic shift in the sense of the term.”[28] explains the sociologist Sam Whimster. Today any leader is likely to be portrayed as “charismatic” as it is most often used synonymously for the adjective "inspirational."[29] Celebrity culture and its supporting media like Facebook, twitter, instagram… have transformed the field in which personalities are depicted and according to Gisela Stuart, a labour MP in the UK parliament, successful modern politicians have to be photogenic and have a likeable personality.

If we look closer at Weber’s writings on charisma, this concept was rarely applied to modern political personalities as it belonged to pre-modern, less rationalized societies. As a result, according to some scholars, assigning charisma to politicians in present times may be contrary to Weber's ideal type. Politics is intended to be normalized and charismatic leadership is circumscribed in the modern and contemporary world by a rational based legitimacy as well as the deadening effects of routinization of the politics and all aspects of life in general. As Karl Mannheim stated in Ideology and Utopia (1929),[30] utopias and worldviews have been overtaken by pragmatic politics.

Thus, charisma after Weber may require a reworking of the classical typology. One option would be to differentiate “Hard charisma” and “Soft charisma”. Hard charisma referring to the totalitarian or authoritarian society where “the place of affect has been seriously degraded through the suppression of society (…) and the omnipresent great leader’”[28] whereas soft charisma “comes out of an affect-saturated society, where low-level emotionalism, momentary aestheticism and narcissism would provide the materials for the soft charismatic leader”.[28] The latter not belonging to the classic Weber formulation in which leaders have an extraordinary godly grace bestowed upon them. However, in both cases the charisma would be artificial and its effectiveness dependent on the arts of presentation and projection especially through the mass media in order to construct a “community of experience” or a “community of feeling”.[23]

However, this typology, even though interesting, seems to be too broad and not effective in studying charisma in democraties. Indeed, as specified by the French philosopher Jean Claude Monod, despite the fact that charisma is commonly associated with authoritarian or totalitarian regimes, its very birth as a category of leadership has been considered in relation to liberal democracies.[27] In a monarchy, the king is chosen by virtue of his blood and charisma does not play a key role in his capabilities. It is also paradoxically true in a totalitarian regime : Hitler’s charismatic leadership is much discussed by historians but if we look at Stalin, it is generally admitted that he had no personal charisma before the machine of propaganda constructed his character of “father of the people”. Even Hannah Arendt considered that the analysis of the Bolshevik or Nazi regimes as charismatic ones was a wrong direction.

Thus, it seems that it is precisely in liberal democracies that charisma plays a key role, as it is a regime governed according to the principle of “a free competition for power, in which personal qualities matter, in order to convince the electors that you are able to become the best leader of a party or of the country.”[27] The political has become “an individualized form of action in which decision, character, intuition, personal charm, and speech play an important part."[27] Still, this entails multiple questions, like: is charisma necessary for liberal democracies? Or more than being a condition, can charisma be a threat to liberal democracies?

To begin with, If liberalism implies a purely self-organizing society governed solely by impersonal norms and laws, then political charisma has nothing to do with liberalism and is necessarily opposed to it. Weber himself didn't believe in such self-organization and thought it was an illusion to believe that liberty and democracy could be guaranteed by the so-called "laws" of the market in the late capitalistic economy. Weber defended a type of political personal responsibility and decision-making, as well as a form of leadership, through which the "masses" could pursue their own interests in the face of capitalistic and bureaucratic forces. This defense, however, was not doomed to destroy the liberal concern for a balance of power, pluralism, and constitutional checks as a means of preventing the "man of the masses" from becoming a tyrant. A strong personal power is also sometimes needed, for example, in times of war or crisis in which the charisma of the leader is of crucial importance. For instance, Churchill, Roosevelt or De Gaulle’s political charisma embodies the spirit of resistance of liberal democracies against totalitarian leaders and their machines of propaganda.

But this context is still exceptional and we can see that during ordinary or peaceful times, charisma can play a key role in a “democratization of democracy”[31] meaning a better implementation of its values life liberty and equality and a challenging of its borders and limits. The leaders of social movements or parties who succeed in “equalizing the conditions of subaltern people"[27] (for example the women, the Black people in the United States, the LGBTQ+ people...), are often gifted with a charisma which fosters emancipation. One example is Martin Luther King known for his speeches and promises of equality. More recently, Barack Obama’s style of charisma during his first campaign is quite similar to Martin Luther King’s one. However, studying Obama's case let us distinguish between the deployment of charisma during and after the campaign, when charisma, more than being personal, becomes also professional. This kind of “mystique” linked to the strong mobilization of the campaign seems to fade away once in power. “Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.” underlined the French poet Charles Péguy.

Nonetheless, as we turn toward the present, we can notice the emergence of a critique of liberalism in the liberal democracies with the idea that liberalism today is an obstacle for a “real” democracy. This critique calls on a more direct democracy in which the leader would have a direct relationship with “the people”.

Charisma : a condition to the rise of populist leaders ?[modifier | modifier le code]

Charisma has been considered as maybe not a condition but at least an important trait in favor of today’s liberal democracy. However, the growing skepticism toward traditional elites and parties or even representative democracy has led to the rise of movements and leaders, frequently described as charismatic : the populist leaders. From Poutine claiming in an interview to the Financial Times in 2019 that “liberalism has become obsolete” to Viktor Orbán characterizing his goal of Hungary as becoming an “illiberal democracy”, the 21st century (and especially the 2nd decade) has been marked by the emergence of multiple populist leaders that were almost all labeled as charismatic. Some scholars have even maintained that charisma is inherent to populism. Thus, we can ask ourselves if charisma is a condition to the rise of populist leaders.

Firstly, we can attempt to define criteria to distinguish : “which democratic political leaders are charismatic and which are not?”[32]. We will use Takis S. Pappas criteria as it seems the most relevant and useful when applied to the study of leadership in contemporary politics. Charisma is related to “extraordinary qualities” of a leader within “the otherwise ordinary political system that liberal democracy is reckoned to be.”[32] But what is extraordinary and what is not?

In Weber’s writings we can notice two dimensions of charismatic leadership: an individual and a collective one. And today we are more familiar with the first one which understands political charisma as “the power of leaders to defy prevailing worldviews on the basis of discourses of justification against the established order, providing a radical founding of a novel structure of legitimacy.”[33] Out of this, T. S. Pappas has established 2 criteria for charismatic leadership in a liberal democracy: the nature of rulership and the aims of rule. When the nature of rulership is personal and the aim is radical, the leadership can be described as charismatic/extraordinary. When it is impersonal and moderated, it can be defined as legal rational/ordinary. (Cf. Table 19.1, Annexe)

Now, if we focus on the charismatic leadership, it can be conceptualized as a “three-level concept” as established in figure 19.1 (cf annexe). Charisma is linked to 2 variables:

- The first one is personalism which is measured through 2 indicators: “the leader’s full authority over a party/movement and the direct and unmediated relationship between the leader and the led”.[32]

- The second one is radicalism which is also measured through 2 indicators : “the legal subversion of the status quo through its systematic delegitimation and the institution in its place of an entirely novel system of authority”.[32]

Before applying these criteria to populism, we can quickly define populism as democratic illiberalism in which “society is split by a single cleavage effectively dividing the vast pure social majority from a tiny corrupted elite minority”[32] and the populist leader aims to satisfy the majority that makes up “the people” by promoting adversity and social hostility. The protection of minorities and the rule of law becomes of secondary importance.

Now when matching these two definitions, the criterion of radicalism in populist charisma is met as populism intends to replace the liberal political democratic order by another which would be democratic but illiberal. If we concentrate on the “personal” component of charisma, we can see that, first of all, most of the populist leaders are “outsiders”[32], originating from nonpolitical family and professional milieus. For example, Berlusconi and Trump were two prominent businessmen while Peron and Chavez were two military men… And even if they had a previous relationship with political parties, they either sever it in order to build a new party or transform their parties and lead them in other personnel directions (for example, Marine Le Pen who transformed the “Front National” created by her father Jean Marie Le pen into the “Rassemblement national”). Another interesting characteristic present in most of the populist leaders considered by T. S. Pappas, is that most of them rose to political prominence by leading parties they had founded themselves. Perón came to power in Argentina in 1946 as head of a party founded the previous year to contest the forthcoming elections. In Hungary, Orban was on of many students who, in 1988, co-founded Fidesz as an liberal independent youth organization. And when they did not found their own parties, populists rose within established parties against intraparty procedure and often bypassing time-honored practices of those parties or transforming liberal parties into populist ones. For instance, Donald Trump, who was not initially the preferred choice of the Republican Party's affluent donors and top officials, was able to stage what resembled a coup by the party's rank, causing the party to split over its identity, basic beliefs, and fundamental principles. Populist leaders also tend to acquire full control over their respective party organizations, eliminating all internal opposition. Another notable aspect is the persistence of populist leaders' charisma. As the experiences of Argentina's Perón, Greece's Papandreou, and Venezuela's Chávez demonstrate, none of these presidents ever lost their charisma as long as they ruled (and they ruled until their natural death.)

As argued by Finchelstein, populism without charismatic leadership remains “historically … an incomplete form”[34] and according to T. S. Pappas it seems clear that “charismatic leadership is the major causal factor and most important predictor of the rise of populism.”[32] making charisma one condition of populists’ leadership. However, we can nuance this affirmation with the study “Populist leaders and coterie charisma” by Duncan McDonnell. The author defined charisma through Weber’s affirmation that “what is alone important is how the individual is actually regarded by those subject to charismatic authority, by his “followers” or “disciples”.[35] By examining how 3 european populist leaders were viewed within their parties and studying the relationship between the leader and followers, D. McDonnell has found that while Bossi exemplifies coterie charisma not just in terms of how followers see his attributes and authority, but also in terms of the intense emotional attachment displayed by his followers, Blocher presents a least convincing case of coterie charisma, particularly because of the weak acceptance of his authority. Therefore, he maintained that “charisma is not necessarily an ever-present feature of the relationship between populist leaders and their parties’ representatives and members.” questioning the fact that populism and charisma go in tandem.

To sum up, while charismatic leadership has been proven as in important trait of liberal democratic leaders as well as paradoxically illiberal populist leaders, it seems interesting to examine the role and place of charisma in today’s politics.

Elitist neoliberal charisma vs illiberal populist charisma: what place for charisma in today’s politics?[modifier | modifier le code]

A common difficulty when using the concept of charisma in social sciences is that it appears to lie upon forms of “recognition” and “habitus” that are socially and culturally diverse. For example, according to Jean-Claude Monod[27], while Trump can be seen as charismatic among the white cultivated upper class, Barack Obama can be viewed as the achievement of charisma by the Black middle class. In the case of Putin, what a russian would view as a confident and calm outlook may be seen as the opposite by an American or South European. Therefore, this questions the possible existence of diverse types of charisma like a cold one and a warm one or rather questions the usage of charisma in the first place to qualify a contemporary leader. Here, the distinction between “charismatic leader,” “ideological leader” and “pragmatic leader”[27] could be useful. For example, Merkel is commonly praised as a pragmatic leader, pragmatism being associated with liberalism, a capacity to make compromises, to think about interests before passions… But as Merkel is also viewed as cold and calm, she is usually considered as uncharismatic.

However, does this mean that “charisma, described by Weber as “a revolutionary force” needs to have a passionate and potentially violent dimension?”.[27] Indeed, as seen with the rise of populist leaders, seriousness and pragmatism tends to be less and less the main qualities expected by many of the voters in today’s liberal democracies. “Tweeting” in personal accounts, mocking on every subject or even making tik toks, seems to be a fact of the second decade of the 21st century with Trump, Boslonaro, Boris Jonhson, Matteo Salvini… As Paulo Gerbaudo noted: “Contemporary leadership is histrionic and excessive when compared with the politics of old. Politicians of the early 20th century emphasized their professionalism, seriousness and reliability: quite the opposite of the self-narration and narcissism that are key ingredients for a successful social media persona today.”[36]This is linked to the beginning of a new era that gives more power to the personality of the leaders and less to the ideology and organization of their parties. Gerbaudo then talks about “Hyperleaders”[36] that have a far larger social media base than their organization. Trump, Salvini but also the French President Emmanuel Macron, would be good examples of these “digital era’s leaders”.

These hyperleaders embody sometimes an authoritarian charisma that many fear because announcing a possible destruction of democracy. According to Llyod, “authoritarian charisma gives the audience what the audience desires. In contrast, democratic charisma invites an audience to develop new desires. . . . It points to the limits of the law and calls us to a higher sense of justice.”[37]Still, challenging the law for the sake of a “higher justice” can eventually go in an antidemocratic direction, for instance, if this “higher justice” is presumed to fit with an exclusive religious law (The ayatollah Khomeini’s charisma for example) or with the superiority of a certain group or race.

In this new era, two main forces seems to have entered a “battle of charismas” or a “worrying face-à-face”[38] where an Elitist neoliberal charisma is confronted to an illiberal populist one. Whereas the first one seems to be a liberalism disconnected from certain crucial aspects of democracy like the sovereignty of the people and their capacity of deciding of the main lines of the government's politics, the second one tends to be more or less of a democracy disconnected from crucial aspects of liberalism like the respect of pluralism or some human rights. On one hand, the Elitist liberal charisma embodied by Macron : perceived as cultivated, smart, comfortable in speech but close to big businesses, banks, and even sometimes as arrogant and scornful, unaware of the social realities of poor people with some economic policies favorable to the wealthiest part of the country. (The rise of the “Gilets jaunes” is one expression of this perception). On the other hand, the illiberal populist one, represented by Orbán or Marine Le Pen, with “their xenophobic defense of the national ethnos”[27]. Historically, the major trend of liberalism and neoliberalism has held that democracy was only valid if it was limited and managed by a rational elite. Does this eliminate the possibility of a "democratic charisma" in the absence of this elitist trend? Isn't there a third option between elitist neoliberal charisma on the one hand, and populist charisma on the other? That is a great avenue for further research.

Conclusion (Salim)[modifier | modifier le code]

To conclude, charisma can be one condition for one efficient form of political leadership as maintained by its theoritical creator Max Weber. However, while considering charisma as a condition or not of political leadership, it is important to note that the charismatic leadership is also a social fact, a social interaction between an emitter and its recipients, a malleable and context-sensitive dynamic that is intrinsically bound to time and that exists mainly in times of crisis. It is also a circular phenomenon sometimes better observed after death through a mystification of the memory of the leader and sometimes that is fatally destined to fade away and disappear after an eventual period of routinisation. It is thus complex to consider charisma as a condition when its very existence is In addition, as charismatic leadership seems to often lead to a form of authoritarian power or at least a quite centralized exercise of power, its relationship with contemporary democracies is somewhat ambiguous, sometimes considered as a condition for being an efficient leader, sometimes considered as a threat to liberalism with the rise of populism. Thus, the “face à face” between an elitist neoliberal charisma and a populist illiberal charisma raises the question of an alternative form of democratic charisma that could embody today’s political needs regarding political leadership.

- → N'hésitez pas à publier sur le brouillon un texte inachevé et à le modifier autant que vous le souhaitez.

- → Pour enregistrer vos modifications au brouillon, il est nécessaire de cliquer sur le bouton bleu : « Publier les modifications ». Il n'y a pas d'enregistrement automatique.

Si votre but est de publier un nouvel article, votre brouillon doit respecter les points suivants :

- Respectez le droit d'auteur en créant un texte spécialement pour Wikipédia en français (pas de copier-coller venu d'ailleurs).

- Indiquez les éléments démontrant la notoriété du sujet (aide).

- Liez chaque fait présenté à une source de qualité (quelles sources – comment les insérer).

- Utilisez un ton neutre, qui ne soit ni orienté ni publicitaire (aide).

- Veillez également à structurer votre article, de manière à ce qu'il soit conforme aux autres pages de l'encyclopédie (structurer – mettre en page).

- → Si ces points sont respectés, pour transformer votre brouillon en article, utilisez le bouton « publier le brouillon » en haut à droite. Votre brouillon sera alors transféré dans l'espace encyclopédique.

- New Oxford American Dictionary, edited by Angus Stevenson and Christine A. Lindberg. Oxford University Press, 2010

- M.Weber, Le Savant et la Politique, 1919

- News, D. (1998, June 7). All senses of the word `charisma' come from Greek. Deseret News. Retrieved December 12, 2021

- Weber, Max, 1864-1920. Max Weber on Law in Economy and Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954.

- Tucker, Robert C. “The Theory of Charismatic Leadership.” Daedalus, vol. 97, no. 3, The MIT Press, 1968, pp. 731–56

- Peter, L. (2017, October 16). Kurz and charisma: What propels young leaders to power? BBC News. Retrieved December 12, 2021,

- Smith, Philip. “Culture and Charisma: Outline of a Theory.” Acta Sociologica, vol. 43, no. 2, Apr. 2000, pp. 101–111

- PAPPAS, Takis S., Political Charisma Revisited, and Reclaimed for Political Science, EUI RSCAS, 2011/60, EUDO - European Union Democracy Observatory

- Schweitzer, Arthur. “Theory and Political Charisma.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 16, no. 2, 1974, pp. 150–181

- Friedrich, Carl J. “Political Leadership and the Problem of the Charismatic Power.” The Journal of Politics, vol. 23, no. 1, [University of Chicago Press, Southern Political Science Association], 1961, pp. 3–24

- Spinrad, William. “Charisma: A Blighted Concept and an Alternative Formula.” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 106, no. 2,

- Schweitzer, Arthur. “Theory and Political Charisma.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 16, no. 2, 1974, pp. 150–181

- Schweitzer, A., 1974. Theory and Political Charisma. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 16(2), pp.150-181.

- Joosse, P., 2014. Becoming a God: Max Weber and the social construction of charisma. Journal of Classical Sociology, 14(3), pp.266-283.

- Steffens, N., Peters, K., Haslam, S. and van Dick, R., 2017. Dying for charisma: Leaders' inspirational appeal increases post-mortem. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(4), pp.530-542.

- Weber, M., 2013. La transformation du charisme et le charisme de fonction. Revue française de science politique, Vol.63(3), p.463.

- Andrews-Lee, C., 2019. The Power of Charisma: Investigating the Neglected Citizen–Politician Linkage in Hugo Chávez's Venezuela. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 11(3), pp.298-322.

- Lacouture, J., 2010. De Gaulle. Paris: Éd. du Seuil.

- De Boisdeffre, P., 1978. De Gaulle Malgré Lui. La Nouvelle Revue des Deux Mondes, pp.61-68.

- Spinrad, W., 1991. Charisma: A Blighted Concept and an Alternative Formula. Political Science Quarterly, 106(2), p.295.

- Simpson, Alan K.; McDaniel, Rodger (2013). "Prologue". Dying for Joe McCarthy's Sins: The Suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt. WordsWorth Press. p.

- Akdeniz, E., 2020. Weber's Charismatic Leadership in Times of Crisis. The Journal of International Social Research,

- Uzelac, G., 2020. Charisma and communities of feeling. Nations and Nationalism, 27(1), pp.130-147.

- Hobbes, T., Krul, W. and Tromp, B., 2007. Leviathan.

- Klein, S., 2016. Between Charisma and Domination: On Max Weber’s Critique of Democracy. The Journal of Politics,

- Nye, J. 2008. The Mystery of Political Charisma, The Wall Street Journal

- Jean-Claude Monod (2020) ”Charisma in liberal democracies”,Routledge International Handbook of Charisma, edited by José Pedro Zúquete, Taylor & Francis Group,

- Whimster, S. (2012). Editorial: Charisma after Weber. Max Weber Studies, 12(2), 155–158.

- Bello WF. (2020) ”A dangerous liaison? Harnessing Weber to illuminate the relationship of democracy and charisma in the Philippines and India.” International Sociology.35(6):691-709.

- Karl Mannheim, (1929) Ideology and Utopia

- Balibar, Etienne. At the Borders of Citizenship: A Democracy in Translation, European Journal of Social Theory, 2010

- Takis S. Pappas, (2020), “Political charisma and modern populism”,Routledge International Handbook of Charisma, edited by José Pedro Zúquete, Taylor & Francis Group,

- Kalyvas, A. (2002). “Charismatic Politics and the Symbolic Foundations of Power in Max Weber.” New German Critique 85: 67–103.

- Finchelstein, F. (2017). From Fascism to Populism in History. Oakland, CA, University of California Press.

- McDonnell, D. (2016). Populist Leaders and Coterie Charisma. Political Studies, 64(3), 719–733.

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. (2019). The Age of the Hyper-Leader: When Political Leadership Meets Social Media Celebrity. New Statesman, 8 March.

- Lloyd, Vincent W. 2018. In Defense of Charisma. New York, Columbia University Press.

- Confavreux, Joseph, ed. 2019. Le Fond de l’air est jaune. Comprendre une révolte inédite, Paris, Seuil.