Edward Franklin Frazier

| Président de l'Association américaine de sociologie | |

|---|---|

| Naissance | |

|---|---|

| Décès | |

| Nationalité | |

| Formation | |

| Activités |

| A travaillé pour | |

|---|---|

| Membre de |

Council on African Affairs (en) |

| Distinctions |

Edward Franklin Frazier, né à Baltimore dans le Maryland aux États-Unis le , décédé le , est un sociologue, universitaire, essayiste américain. Il a étudié les relations raciales aux Amériques et en Afrique, les structures de la famille et de la bourgeoisie afro-américaines. Il est cofondateur de The District of Columbia Sociological Society dont il a été président entre 1943 et 1944. Edward Franklin Frazier a été l'un des Afro-Américains les plus influents auprès des institutions et sur les pratiques visant à faire accepter les demandes d'égalité économique, sociale et politique dans la société américaine.

Biographie

[modifier | modifier le code]

Fils de James H. Frazier, directeur d'une agence de banque, et de Mary Clark Frazier[1], mère au foyer de cinq enfants[2], Edward Franklin Frazier[3] commence sa scolarité à l'école publique de Baltimore. Son père meurt alors qu'il a 10 ans. Il fait de petits métiers pour aider sa famille. En juin 1912 il est diplômé de la Colored High School et obtient une bourse pour étudier à l'Université Howard de Washington DC. Il suit les cours de latin, grec et mathématiques et, en option, l'art dramatique et la science politique avec d'excellents résultats.

Trajectoire intellectuelle

[modifier | modifier le code]Frazier commence sa carrière durant la Première Guerre mondiale tout en poursuivant ses études universitaires. Il enseigne tout d'abord les mathématiques au Tuskegee Institute dans l'Alabama en 1916-1917. Il publie cette année-là un pamphlet contre la guerre God and War[4]. L'année suivante, il enseigne l'anglais et l'histoire à St. Paul's Normal and Industrial School, Lawrenceville, Brunswick, Virginie. Durant sa troisième année de professorat, 1918-1919, il enseigne le français et les mathématiques à la Baltimore High School.

En 1920, Frazier obtient son master en sociologie à l'université Clark de Worcester, Massachusetts avec le sujet Les Nouveaux Courants de pensée parmi les Gens de couleur en Amérique. Et, cours de l'année 1920-1921, il bénéficie du soutien de la Fondation Russel Sage[5] pour étudier à l'École de sociologie de New York, devenue le département de Sociologie de l'université Columbia[6] puis il passe une année à l'Université de Copenhague grâce à une bourse de la Fondation Amérique Scandinavie[7].

Entre 1922-1927, Frazier est chercheur à l'Université d'Atlanta[note 1] où il devient directeur de l'école de sociologie du travail et professeur de Sociology à la Morehouse College qui reçoit des étudiants masculins et afro-américains. C'est durant ces années qu'il commence à écrire The Negro Family. Il publie The Pathology of Race Prejudice dans le numéro de juin 1927 de la revue Forum et provoque une controverse. Il est contraint de quitter Morehouse College.

La famille afro-américaine

[modifier | modifier le code]Frazier quitte l'université d'Atlanta pour aller enseigner à l'université de Chicago et s'engage dans la rédaction de sa thèse à partir de 1927. Il obtient son Ph.D. dans cette université, en 1931[8], à l'âge de 38 ans, avec le sujet The Negro family in Chicago. Le thème fera l'objet d'un ouvrage la même année sous le titre The Free Negro family : a study of family origins before the civil war puis d'une publication définitive The Negro Family in the United States en 1940[9]. Le travail de recherche analyse les forces historiques et culturelles qui ont influencé le développement humain et les structures des familles descendantes d'Africains dans l'hémisphère nord-américain depuis la création des sociétés coloniales esclavagistes. Il obtiendra, dès sa publication, le prix Anisfield-Wolf, attribué au travail de recherche le plus significatif dans le domaine des relations inter-ethniques créées par l'organisation des groupes sociaux selon la race, dans les sociétés coloniales esclavagistes[10] et les Treize colonies, remodelées par les théories et pratiques raciales du XIXe siècle et la ségrégation au XXe siècle. Pionnier dans ce champ de recherches sociologiques, Frazier participera à la rédaction de la déclaration sur La Question raciale de l'Unesco[11], en 1950, à la Maison de l'Unesco, Paris. Il est alors devenu un membre éminent du courant de pensée de l'École de sociologie de Chicago.

Voyage au Brésil

[modifier | modifier le code]En 1941, Frazier embarque, en compagnie de sa famille, pour un séjour d'études d'une année au Brésil. Le voyage est financé par un Guggenheim Fellowship. De ce séjour résulteront les textes :

- The Negro Family in Bahia, Brazil ;

- Some Aspects of Race Relations in Brazil ;

- Rejoinder to Melville J. Herskovits ;

- The Negro in Bahia, Brazil : A Problem in Method ;

- Comparison of Negro-White Relations in Brazil and in the United States.

Carrière à l'université Howard

[modifier | modifier le code]Après son voyage au Brésil, Frazier s'installe pour deux décennies à l'université Howard. Ses recherches vont se concentrer alors sur l'environnement des collèges pour Afro-Américains, particulièrement celui de l'université Howard. Vers la fin de cette période, Frazier rencontrera Nathan Hare, sociologue et psychothérapeute, auteur de The Black Anglo-Saxons, ouvrage classique sur les Afro-américains individualistes des classes moyennes qui auraient abandonné leur propre culture et refuseraient d'assumer leurs responsabilités comme avocats de l'ensemble des Afro-Américains[12].

Bourgeoisie afro-américaine

[modifier | modifier le code]Bourgeoisie Noire, publié en français en 1955, traduit en anglais en 1957, est une critique du conservatisme — analysé comme obséquieux — de la classe moyenne afro-américaine qu'elle a hérité de la culture et de la religion des classes moyennes anglo-saxonnes, vues comme intellectuellement et culturellement stériles.

Présidence d'associations de sociologie

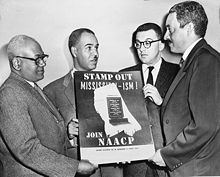

[modifier | modifier le code]Dès ses années d'université, Frazier participe à la vie publique des États-Unis. ses activités au sein de la National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)[note 2] et de la société socialiste interuniversitaire (en) développent son charisme et ses compétences de leadership. Il est élu président de sa promotion en 1915 et en 1916.

Frazier a été membre fondateur de la The District of Columbia Sociological Society[13] dont il a été président entre 1943 et 1944. Il sera président de la Eastern Sociological Society (en)[14] l'année suivante, 1944-1945. En 1948, il devient le premier Afro-américain président de l'Association américaine de sociologie et donne sa conférence inaugurale sous le titre Race Contacts and the Social Structure en décembre de la même année. Cette conférence se place dans le débat avec Melville Herskovits sur la nature des contacts culturels dans le monde occidental en référence avec les Africains, les Européens et leurs descendants.

Actif dans le mouvement contre la ségrégation

[modifier | modifier le code]

À la conférence de la National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) en 1933, avec ses collègues Ralph Bunche et Abram Lincoln Harris, Frazier s'opposat à la précédente génération des leaders du mouvement, tel W.E.B. Dubois. Un ouvrage récent fait l'historique de cette conférence : Confronting the Veil de Jonathan Scott Holloway (en)[15].

Frazier fut également, membre de Alpha Phi Alpha, la première fraternité interuniversitaire à avoir été créée par des Afro-Américains, fondée le 4 décembre 1906 sur le campus de l'Université Cornell à Ithaca, dans l'État de New York.

À sa mort en 1962, Frazier compte parmi les Afro-américains les plus influents auprès des institutions et pour l'acceptation des revendications pour l'égalité économique, politique et sociale dans la société américaine.

Bibliographie

[modifier | modifier le code]Cette liste chronologique est établie principalement d'après la bibliographie de la Social Work Library[16]

Ouvrages

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1932 : The Negro Family in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, [1932]. (MSRC M321.1 F86ne).

- 1932 : The Free Negro family : a study of family origins before the civil war. Nashville: Fisk University Press, 1932. (Social Work E185 F83).

- 1939 : The Negro Family in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939. (Founders E185.86 .F74 ; Divinity E185.86 .F74).

- 1940 : Negro Youth at the Crossways, Their Personality Development in the Middle States. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 1940. (Divinity E185.6 .F74).

- 1949 : The Negro in the United States. New York: Macmillan Co., 1949. (Divinity E185 F833).

- s.d. : God and War. [n.p.], [n.d.]. (MSRC M231 F869)

Collaborations à des ouvrages collectifs

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1925 : "Durham: Capital of the Black Middle Class." in The New Negro, by Alain Locke. New York: A. and C. Boni Company, 1925. 333-40. (Founders NX512.3.N5 L6 1970).

- 1929 : "La Bourgeoisie Noire." in Anthology of American Negro Literature, by V.F. Calverton. New York: The Modern Library, 1929. 379-88.

- 1934 : "Traditions and Patterns of Negro Family Life." in Race and Culture Contacts. Ed. Edward B. Reuter. . New York: McGraw-Hill Company 1934. 191-207. (Founders HT1521 A5).

- 1946 : "The Negro Now." Contact, Book 2: Britain Between West and East (1946). 61-63.

- 1947 : "The Racial Issue." in Unity and Difference in American Life. Ed. R.M. MacIver. New York: Harper and Bros., 1947. 43-59.

- 1947 : "A World Community and a Universal Moral Order." in Approaches to Group Understanding, for Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion in their Relations to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc. Ed. Lymon Bryson, Louis Finkelstein, and R. M. MacIver. New York: Harper and Bros., 1947. 443-52. (Founders HM101 C678 1945).

- 1948 : "The Negro Family." in The Family: Its Function and Destiny. Ed. Ruth Nanda Anshen. New York: Harper and Bros., 1948. 142-58. (Founders HQ728 A74).

- 1948 : "Post High School Education of Negroes in New York State." chap. 8 in Inequality of Opportunity in Higher Education, a study of Minority Group and Related Barriers to College Admission, published in A Report to the Temporary Commission on the Need for a State University, by David S. Kerkowitz. Albany: William Press, 1948. 159-74.

- 1948 : "Supplementary Studies" in Inequality of opportunity in higher education; a study of minority group and related barriers to college admission: a report to the Temporary Commission on the Need for a State University, by David S. Berkowitz. Albany: Williams Press, 1948.

- 1949 : "Sociologic Factors in the Formation of Sex Attitudes." in Psychosexual Development in Health and Disease. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1949. 244-55.

- 1952 : "The Negro and Racial Conflicts." in One America. Ed. Francis J. Brown and Joseph S. Roucek. New York: Prentice Hall, 1952. 492-504.

- 1955 : "The Negro in the United States." in Race relations in World Perspective. Ed. Andrew W. Lind. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1955, p. 339-70.

- 1955 : "Impact of Colonialism on African Social Forms and Personality." in Publication of Norman Harris Memorial Foundation Lectures on Africa in the Modern World. Ed. Calvin W. Stillman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955. 70-96.

- 1955 : "Commentary on "The Impact of Western Education on the African's Way of Life." in Africa Today. Ed. C. Grove Haines. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1955. 166-71. (Founders DT5 H25).

- 1957 : "The Cultural Background of Southern Negroes." in Selected Papers of the Institute on Cultural Patterns of Newcomers, Welfare Council of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, October 1957.1-14.

- 1957 : "Introduction" in Caribbean Studies: A Symposium. Ed. Vera Rubin. Jamaica, B.W.I.: University College of the West Indies, 1957. v-viii (MSRC M972.9 R82).

- 1959 : "Potential American Negro Contributions to African Social Development." in Africa: Seen by American Negroes, Presence Africaine. Paris: Presence Africaine, 1959. 263-78. (Founders DT14 A35).

- 1961 : "Negro Harlem: An Ecological Study." in Studies in Human Ecology. Ed. George A. Theodorson. Evanston, Ill: Row, Peterson and Company, 1961. 165-74. (Founders HM206 T48 1961B).

- 1961 : "Desegregation as an Object of Sociological Research." in Human Behavior and Social processes: An Interactionist Approach. Ed. Arnold Rose. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1961. 698-24. (Founders HM131 R78).

- 1961 : "Negro, Sex Life of the African and American." in The Encyclopedia of Sexual Behavior. New York: Hawthorne Books, 1961. 769-75. (Founders HQ9 E4).

- 1961 : "Racial Problems in World Society." in Race Relations and Theory: Essays in Honor of Robert E. Park. Ed. Jitsuichi Masuoka and Preston Valien. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1961. 38-50.

- 1961 : "The Socialization of the Negro Child in the Border and Southern States." in A Casebook. Ed. Yehudi A. Cohan. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Wilson, 1961. 45-53.

Œuvres en français

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1952 : "Problèmes de L'Étudiant Noir aux États-Unis." in Les Étudiants Noirs Parlent. Paris : Présence Africaine, 1952. 275-83.

- 1955 : Bourgeoisie noire. Paris: Librairie Plon, 1955,1969. (MSRC M323 F86 b2)[17].

Œuvres traduites en français

[modifier | modifier le code]Essais et articles de presse

[modifier | modifier le code]1922 - 1940

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1922 : "The Folk High School at Roskilde." Southern Workman 51 (July, 1922) :325-28l.

- 1922 : "Danish People's High Schools and America." Southern Workman 9 (September, 1922) :425-30.

- 1923 : "Cooperation and the Negro." Crisis 5 (March, 1923) :228-29.

- 1923 : "The Cooperative Movement in Denmark,

Danemark." Southern Workman 52 (September, 1923) :479-84.

Danemark." Southern Workman 52 (September, 1923) :479-84. - 1923 : "Neighborhood Union in Atlanta." Southern Workman 52 (September, 1923) :437-42.

- 1923 : "Training Colored Social Workers in the South." Journal of Social Forces 1 (May, 1923) :440-46.

- 1924 : "The Negro and Non-resistance." Crisis 27 (March, 1924) :213-14.

- 1924 : "Discussion." (Health Conditions in the South). Opportunity 2 (August, 1924) :259.

- 1924 : "Cooperatives: the Next Step in the Negro's Development." Southern Workman 53 (November, 1924) :505-9.

- 1924 : "Some Aspects of Negro Business." Opportunity 2 (October, 1924) :293-97.

- 1924 : "A Negro Industrial Group." Howard Review 1 (June, 1924) :196-211.

- 1924 : "A Note on Negro Education." Opportunity 2 (March, 1924) :75-77.

- 1924 : "Social Work in Race Relations." Crisis 27 (April, 1924) :252-254.

- 1925 : "All God's Chillun Got Eyes." Crisis 29 (April, 1925) :254.

- 1925 : "Social Equality and the Negro." Opportunity (Journal of Negro of Life) 3 (June, 1925) :165-168.

- 1925 : "A Community School." Southern Workman 54 (October, 1925) :495-64.

- 1925 : "Psychological Factors in Negro Health." Social Forces 3 (March, 1925) :488-90.

- 1926 : "Family Life of the Negro in the Small Town." Proceedings of the National Conference of Social Work (1926), p. 384-388.

- 1926 : "Garvey: a Mass Leader." [New York], 128 (August, 1926) 147-48.

- 1926 : "The Garvey Movement." Opportunity 4 (November, 1926) :346-48.

- 1926 : "How Present Day Problems of Social Life Affect the Negro." Hospital Social Service 13 (1926) :384-93.

- 1926 : "Three Scourges of the Negro Family." Opportunity 4 (July, 1926) :210-1, 234.

- 1926 : "King Cotton." Opportunity (February, 1926) :50-55.

- 1926 : "What is Social Equality." (with John Haynes). The World Tomorrow 9 (April, ) :113-14.

- 1927 : "Is the Negro Family a Unique Sociological Unit?" Opportunity 5 (June, 1927) :165-8.

- 1927 : "Negro in the Industrial South." Nation 75 (July, 1927) :83-84.

- 1927 : "The Pathology of Race Prejudice." Forum 70 (June, 1927) :856-62.

- 1928 : "Folk Culture in the Making." Southern Workman 57 (1928) :195-99.

- 1928 : "The American Negro's New Leaders." Current History 28 (April, 1928) :56-59.

- 1928 : "The Mind of the American Negro." Opportunity 6 (September, 1928) :263-66, 284.

- 1928 : "The Negro Family." The Annals of the American Acdemy of Political and Social Science 130 (November, 1928) :21-25.

- 1928 : "Professional Education for Negro Social Workers." Hospital Social Service 18 (1928) :167-76.

- 1929 : "Chicago, a Cross Section of Negro Life." Opportunity 7 (March, 1929) :70-73.

- 1929 : "The Negro Community, a Cultural Phenomenon." Social Forces 7 (March, 1929) :415-420.

- 1930 : "La Bourgeosie Noire." The Modern Quarterly 5 (1928-30) :78-84.

- 1930 : "The Negro Slave Family." The Journal of Negro History 15 (April, 1930) :198-206.

- 1930 : "Occupational Classes Among Negroes in Cities." The American Journal of Sociology 35 (March, 1930) :718-38.

- 1930 : "The Occupational Differentiation of the Negro in Cities." Southern Workman 57 (May, 1930) :196-200.

- 1931 : "Certain Aspects of Conflict in the Negro Family." Social Forces 10 (October, 1931) :76-84.

- 1931 : "The Changing Status of the Negro Family." Social Forces 9 (March, 1931) :386-93.

- 1931 : "Family Disorganization among Negroes." Opportunity 9 (1931) :204-207.

- 1931 : "Some Aspects of Family Disorganization among Negros." Opportunity 9 (July, 1931) :204-7.

- 1932 : "An Analysis of Statistics on Negro Illegitimacy in the United States." Social Forces 9 (December, 1932) :249-57.

- 1933 : "Children in Black and Mulatto Families." The American Journal of Sociology 39 (July, 1933) :12-29.

- 1933 : "The Negro and Birth Control." Birth Control Review (March, 1933) :68-70.

- 1933 : "Graduate Education in Negro Colleges and Universities." The Journal of Negro Education 2 (July, 1933) :329-41.

- 1935 : "The Status of the Negro in the American Social Order." The Journal of Negro Education 4 (July, 1935) :293-307.

- 1936 : "A Critical Summary of Articles Contributed to Symposium on Negro Education." The Journal of Negro Education 5 (July, 1936) :531-33.

- 1936 : "The Dubois Program in the Present Crisis." Race 1, no. 1 (Winter, 1935-36) :11-13.

- 1937 : "The Impact of Urban Civilization upon Negro Family Life." American Sociological Review 2 (August, 1937) :609-18.

- 1937 : "Negro Harlem: an Ecological Study." American Journal of Sociology 43 (July, 1937) :72-88.

- 1938 : "Some Effects of the Depression on the Negro in Northern Cities." Science and Society 2 (Fall, 1938) :489-99.

- 1939 : "The Present Status of the Negro in the American Social Order." The Journal of Negro Education 8 (July, 1939) :376-82.

1941 - 1962

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1940 : "The Negro Family and Negro Youth." The Journal of Negro Education 9 (July, 1940) :290-299.

- 1940 : "The Role of the Negro in Race Relations in the South." Social Forces 19 (December, 1940) :252-258.

- 1942 : "Brazil Has No Race Problems." Common Sense 11 (November, 1942) :363-65.

- 1942 : "Ethnic and Minority Groups in Wartime with Special Reference to the Negro." The American Journal of Sociology 48 (November, 1942) :369-77.

- 1942 : "The Negro Family in Bahia, Brazil,

Brésil." American Sociological Review 7 (August, 1942) :465-78.

Brésil." American Sociological Review 7 (August, 1942) :465-78. - 1942 : "Some Aspects of Race Relations in Brazil,

Brésil." Phylon, (Third Quarter, 1942) :284-95.

Brésil." Phylon, (Third Quarter, 1942) :284-95. - 1943 : "A Negro looks at the Soviet Union,

Union soviétique." Proceedings of the Nationalities Panel, The Soviet Union, A Family of Nations in the War. National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, New York, N.Y. November 1943.

Union soviétique." Proceedings of the Nationalities Panel, The Soviet Union, A Family of Nations in the War. National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, New York, N.Y. November 1943. - 1943 : "Rejoinder to Melville J. Herskovits' 'The Negro in Bahia, Brazil: A Problem in Method',

Brésil." American Sociological Review 8 (August, 1943) :402-404

Brésil." American Sociological Review 8 (August, 1943) :402-404 - 1944 : "Comparison of Negro-White Relations in Brazil and in the United States,

Brésil." Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Series 2, 6, 7, (May, 1944) :251-269.

Brésil." Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Series 2, 6, 7, (May, 1944) :251-269. - 1944 : "Race: an American Dilemma." Crisis 51 (April 1944) :105-6.

- 1944 : "Role of Negro Schools in the Post-War World." The Journal of Negro Education 13 (Fall, 1944) :464-73.

- 1945 : "The Booker T. Washington Papers." The Library of Congress Quarterly Journal of Current Acquisitions 2 (February, 1945) :23-31.

- 1946 : "Significant Study of Urban Negro Life." Crisis 53 (janvier 1946) :25-27.

- 1946 : "Children and Income in Negro Families." (with Eleanor Bernert). Social Forces 25 (December, 1946) :178-82.

- 1947 : "Sociological Theory and Race Relations."American Sociological Review 12 (June, 1947) :265-71.

- 1948 : "Ethnic Family Patterns: The Negro in the United States." American Journal of Sociology 53 (May, 1948) :435-38.

- 1948 : "The Social Status of the Negro." Les Études Américaines, 1948.

- 1949 : "Race Contacts and the Social Structure." American Sociological Review 14 (February, 1949) :1-11.

- 1950 : "Problems and Needs of Negro Children and Youth Resulting from Family Disorganization." The Journal of Negro Education 19 (1950) 269-77.

- 1950 : "Frazier Urges Public Campaign to Implement Court Decisions." Teachers' Bulletin 1 (1950) :3.

- 1953 : "Sociological Aspects of Race Relations." Courier ( August-September, 1953) :1.

- 1953 : "Theoretical Structure of Sociology and Sociological Research." The British Journal of Sociology 4 (December, 1953) :293-211.

- 1957 : "The Negro Middle Class and Desegregation. " Social Problems 4 (April, 1957 ) :291-301.

- 1957 : "Race Relations in World Perspective." Sociology and Social Research 41 (May-June, 1957) :331-35.

- 1958 : "Areas of Research in Race Relations." Sociology and Social Research 42 (July-August, 1958) :424-29.

- 1959 : "Urbanization and Social Change in Africa[18]." Sais Review 3 (Winter, 1959) :3-9.

- 1961 : "Urbanization and its Effects upon the Task of Nation-Building in Africa South of Sahara[18]." The Journal of Negro Education 30 (Summer, 1961) :214-22.

- 1962 : "The Failure of the Negro Intellectual." Negro Digest (February, 1962) :26-36.

Publications posthumes

[modifier | modifier le code]Ouvrages

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1965 : Race and Culture Contacts in the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press, 1965. (Founders HT1521 F68 1965).

- 1966 : The Negro Church in America. New York: Schocken Books, 1966, c1963. (Founders BR563 N4 F7 1966B).

- 1968 : Negro Freedmen. New York: Arno Press, 1968.

- 1968 : E. Franklin Frazier on Race Relations: Selected Papers, ed. with an Introduction by G. Franklin Edwards. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968.( Founders E185 F835 1968).

- 1979 : Black Bourgeoisie: the Rise of a New Middle Class in the United States. New York: Collier Books [1979, c1957]. (Social Work E185.61 F833 1979).

- 1997 : The Black Bourgeoisie. New York: Free Press Paperbacks published by Simon & Schuster, 1997. (UGL Circulation, E185.86 .F72813 1997 Auxiliary Coll.).

Collaborations à des ouvrages collectifs

[modifier | modifier le code]- 1964 : "Black Bourgeoisie: Public and Academic Reactions." in Reflections on Community Studies. Ed. A.L. Vidich, et. al. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1964. 305-311, 349.

- 1969 : "The Garvey Movement" in The Making of Black America, by August Meier. New York: Atheneum, 1969. 204-208. (Founders; Divinity E185 M43).

- 1980 : "Review of Myrdal's 'An American Dilemma'." in Sociology of Race Relations. N.Y.: Free Press, c1980. 159-162. (Founders HT1521 S546).

- 1994 : "La Bourgeoisie Noire." in The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader, New York : Viking, 1994. 173-181. (MSRC M810.8 P828 1994).

Essais et articles de presse

[modifier | modifier le code]- 2009 : E. Franklin Frazier, « Garvey: A Mass Leader, 1926 », sur thenation.com, The Nation, (consulté le )[19].

Notes et références

[modifier | modifier le code]Notes

[modifier | modifier le code]- L'université d'Atlanta est un établissement historiquement noir constituée des deux facultés qui figuraient dans le mouvement des droits civiques : Morehouse College (hommes) et Spelman College (en) (femmes).

- En français : Association nationale pour l'avancement des gens de couleur.

Références

[modifier | modifier le code]- (en-US) « E. Franklin Frazier », sur American Sociological Association, (consulté le )

- (en-US) « Edward Franklin Frazier | Encyclopedia.com », sur www.encyclopedia.com (consulté le )

- (en) « E. Franklin Frazier | American sociologist », sur Encyclopedia Britannica (consulté le )

- E. Franklin Frazier, 1894-1962

- Russel Sage Foundation

- Columbia University, Departement of Sociology

- American Scandinavian Foundation

- (en) Wilma Peebles-Wilkins, « Frazier, Edward Franklin », Encyclopedia of Social Work, (DOI 10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.692, lire en ligne, consulté le )

- Edward Franklin Frazier, The Negro family in the United States : Preface by W. BurgessXVIIe – XXe siècle : 1650-1940, Chicago, University of Chicago press, .(BNF 32127745)

- Bastide Roger, « Dans les Amériques noires : Afrique ou Europe ? », sur persee.fr, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations. 3e année, N. 4, 1948. pp. 409-426, (consulté le )

- Mozell C. Hill, « Research on the Negro Family », sur jstor.org, National Council on Family Relations, (consulté le )

- Andrea G. Hunter, [url google Teaching the Classics in Family Studies: E. Franklin Frazier's], The Negro Family in the United States : XXe – XXIe siècle : 1939-2006, USA, Editions, . Abstract: This paper reintroduces E. Franklin Frazier's 1939 book, The Negro Family in the United States, to family scholars and graduate students and highlights its importance as a groundbreaking and classic text, provides both an introduction to the major thesis of this monograph and a reading of the text, and discusses the challenges of reading classic works and suggests strategies that can be used to guide graduate students in a critical reading of classic works.

- s:La Société coloniale - Abolition de l’esclavage

- Unesco, La Question raciale. L'UNESCO et son programme ; Volume 3 ; 1950, Publication no 792.

- Nathan Hare, The Black Anglo-Saxons : XXe siècle : 1965-1991, Paris, Third World Press, . Compte-rendu de lecture "In their natural struggle to throw off the smothering blanket of social inferiority, they exaggeratedly seek to sever their own historical past in order better assume that of the biological descendants of the Anglo-Saxons" (Dans leur lutte naturelle pour rejeter l'étouffant préjugé d'infériorité sociale, ils cherchent exagérément à se couper de leur propre passé historique pour mieux assumer celui des descendants biologiques de l'Anglo-Saxons) Black World/Negro Digest, mai 1962. Fondée en 1943, Negro Digest, devenue plus tard “Black World (en)” a été créée par Johnson Publishing (en). Durant les difficiles années marquées par le Mouvement pour les droits civiques, 1950-1960, Negro Digest/Black World a été, en matière de développement de la pensée politique, une référent pour les supporters du mouvement qui abolit la ségrégation raciale.

- The District of Columbia Society, DCSS, fondée en 1934 est l'une des plus anciennes sociétés régionales de sociologie aux États-Unis

- Fondée en 1930, l'Eastern Sociological Society est une association sans but lucratif pour les études et la recherche en sociologie

- Jonathan Scott Holloway, Confronting the Veil : Abram Harris Jr., E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche, 1919-1941 : XIXe siècle : 1919-1941, North Carolina, University of North Carolina Press, . (BNF 41381964).

Jonathan Scott Holloway, « Confronting the Veil, Abram Harris Jr., E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche, 1919-1941 », sur uncpress.unc.edu, uncpress.unc, s.d. (consulté le ). - Audrey Thompson, Acting Librarian, Social Work Library, « E. Frankin Frazier, 1894-1962, Sociologist, Educator, Author, Scholar. A Bio-Bibliography », sur www.howard.edu, Howard University Libraries, (consulté le )

- Edward Franklin Franklin (1894-1962), Bourgeoisie noire : XIXe – XXe siècle : 1894-1962, Paris, Plon, .(BNF 32127743)

- Voir : Panafricanisme, Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, UNIA

- "Garvey: a Mass Leader." [New York], 128 (August, 1926) 147-48

- Sociologue américain

- Boursier Guggenheim

- Étudiant de l'université Howard

- Étudiant de l'université de Copenhague

- Étudiant de l'université Columbia

- Docteur de l'université de Chicago

- Professeur à l'université de Chicago

- Naissance en septembre 1894

- Naissance à Baltimore

- Décès en mai 1962

- Étudiant de l'université Clark

- Décès à 67 ans

- Président de l'Association américaine de sociologie