Utilisateur:Damy811/Brouillon

The Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913, officially the Woman Suffrage Procession, was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C.. Organized by the suffragist Alice Paul for the National American Woman Suffrage Association, thousands of suffragists marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1913. The march was scheduled on the day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded", as the official program stated.

Le défilé des suffragettes de 1913 (The Woman Suffrage Parade), officiellement la procession des suffragettes, a été la première marche suffragette à Washington. Organisé par la suffragette Alice P.aul pour l'association nationale des suffragettes Américaines, des milliers de suffragettes marchèrent le long de l'avenue de Pennsylvanie à Washington, le 3 mars 1913. Le défilé fut prévu le jour précédent que le président Woodrow Wilson présente sa première inauguration pour "marcher dans un esprit de protestation contre l'organisation politique actuelle de la société , dont chaque femme est exclue", tel le programme officiel déclaré.

The march and the attention it attracted were monumental in advancing women's suffrage in the United States.[1]

Le défilé et l'attention a été attirée dans l'important avancement du droit de vote des femmes aux États-Unis.[1]

The Beginning[modifier | modifier le code]

Le commencement[modifier | modifier le code]

American suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns spearheaded a drive to adopt a national strategy for women's suffrage in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Both women had been influenced by the militant tactics used by the British suffrage movement and recognized that the women from the six states that had full suffrage at the time comprised a powerful voting bloc. They submitted a proposal to Anna Howard Shaw and the NAWSA leadership at their annual convention in 1912. The leadership was not interested in changing their state-by-state strategy and rejected the idea of holding a campaign that would hold the Democratic Party responsible. Paul and Burns appealed to prominent reformer Jane Addams, who interceded on their behalf.[2]

Les suffragettes Alice Paul et Lucy Burns, on voulu adopter une stratégie nationale pour le suffrage des femmes dans l'association nationale des suffragettes Américaines. Les deux femmes ont été influencées par les tactiques militantes utilisé par le mouvement des suffragettes britanniques et a reconnu que les femmes des six États qui avaient le plein suffrage à ce moment comprenaient un bloc de vote puissant. Ils ont proposés une suggestion à Anna Howard Shaw et aux dirigeants de la NAWSA à leur convention annuelle en 1912. Les meneurs n'étaient pas intéressés par l'idée de changer leurs stratégies état par état et ont rejetés l'idée d'avoir une campagne portant sur le parti démocratique responsable. Paul et Burns lancèrent un appel à l'important réformateur Jane Addams, qui a intercédé en leur nom.[3]

The women persuaded NAWSA to endorse an immense suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. that was to coincide with newly elected President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration the following March. Paul and Burns were appointed chair and vice-chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee.[4] They recruited Crystal Eastman, Mary Ritter Beard, and Dora Lewis to the Committee and organized volunteers, planned for, and raised funds in preparation of the parade with little help from the NAWSA.[5] Affiliates of NAWSA from various states organized groups to march and activities leading up to the march, such as the Suffrage Hikes.[6] Plans for the march were threatened when black suffragists announced they intended to participate, which lead white southern suffragists to threaten to boycott the event.[7] One solution discussed was segregating the black suffragists in a separate section to mollify white southern delegates.[8]

Les femmes ont persuadées la NAWSA d'approuver un défilé pour l'immense suffrage à Washington qui a coïncidé avec l'inauguration de l'élection du président Woodrow Wilson. Paul et Burns ont été nommés au siège et au vice-siège du comité du congrès de la NAWSA.[9] Ils recrutèrent Crystal Eastman, Mary Ritter Beard, et Dora Lewis au comité et sont organisés bénévolement, pour planifier, et atteindre les fonds dans la préparation du défilé avec une petite aide provenant de la NAWSA.[10] Les affiliés de la NAWSA, de divers États groupés, organisent une parade , comme le Suffrage Hikes.[11] Les plans pour le défilé ont étés menacés lorsqu'un suffragiste noir à annoncé son intention de participer, qui conduisent les suffragettes blanches du sud ont menacées de boycotter l'événement.[7] Une solution a été discuté pour la ségrégation des suffragettes noires dans une section distincte pour apaiser les déléguées du sud blanches.[8]

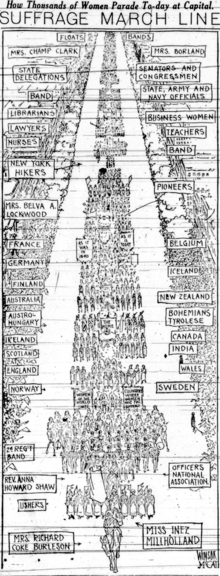

The parade itself was led by labor lawyer Inez Milholland, dressed dramatically in white and mounted on a white horse,[12] and included nine bands,[13] five mounted brigades, 26 floats, and close to 8,000 marchers,[14] including many notables such as Helen Keller, who was scheduled to speak at Constitution Hall after the march. Individuals came from European nations, Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries around the world to support the movement. Most of the women marched in groups determined by their occupation or under their respective banners. Jeannette Rankin, from Montana, marched proudly under her state sign, only to return to Washington, D.C. four years later as the first U.S. congresswoman.[15]

After a good beginning, the marchers encountered crowds, mostly male, on the street that should have been cleared for the parade. They were jeered and harassed while attempting to squeeze by the scoffing crowds, and the police were sometimes of little help, or even participated in the harassment. The Massachusetts and Pennsylvania national guards stepped in. Eventually, boys from the Maryland Agricultural College created a human barrier protecting the women from the angry crowd and helping them progress forward to their destination.[16] Over 200 people were treated for injuries at local hospitals.[17] Despite all this, most of the marchers finished the parade and viewed an allegorical tableau presented near the Treasury Building.[1] Later, after Congress investigated the lack of police protection, the chief of police was fired.[15]

La parade elle-même fut dirigée par l'avocate du travail Inez Milholland, habillée de façon spectaculaire en blanc et montée sur un cheval blanc,[18] et inclus neuf bandes ,[19] cinq brigades montées, vingt-six flotteurs, et environ 8000 marcheurs, [20] incluant beaucoup de notables tel que Helen Keller, qui a pour projet de parler après la marche au Constitution Hall. Les personnes venant de l'Europe, du Canada, de l'Inde, de l'Australie, de la Nouvelle Zélande et beaucoup d'autres pays autour du monde supportent le projet. La plupart des femmes ont marché dans leurs groupes de leur occupation ou de leur étendard respectif. Jeannette Rankin, du Montana, a marché fièrement au nom de son état, pour ensuite retourner à Washington quatre ans après et travailler comme première membre du Congrès des États-Unis.[15]

Après un bon début, les marcheurs rencontrèrent des foules, particulièrement masculines, dans les rues qui devait avoir été nettoyé à cet effet. Ils ont été raillé et harcelés, tout en se faisant écraser les foules railleurs, et la police a parfois donné une petit aide, ou participé au harcèlement. Le Massachusetts et la Pennsylvanie sont intervenus. Éventuellement, les garçons du Maryland Agricultural College on fait une barrière humaine pour protéger les femmes de la foule énervée et les ont aidés à progresser vers leur destination.[16] Plus de 200 personnes ont étés pris en charge pour des blessures aux hôpitaux locaux.[21] Malgré tout cela, la plupart des marcheurs ont fini la parade et on vus un tableau vivant allégorique présenté proche du bâtiment du Trésor.[1] Plus tard, après que le Congrès ait étudié le manque de protection de police, le chef de la police à été tué par balle.[15]

Racism[modifier | modifier le code]

Racisme[modifier | modifier le code]

Considerable debate exists about the segregation of Black woman suffragists in the Parade. In a 1974 oral history interview, Alice Paul recalled the "hurdle" of Mary Church Terrell planning to bring a delegation from the National Association of Colored Women.[22] Delegations from the National Association of Colored Women and from the newly established Alpha Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority from Howard University participated and black women marched in various state and occupational groups. While in Paul's memory a compromise was reached to order the parade as white women, then the men's section, and finally the Negro women's section, reports in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People paper, The Crisis, depict events unfolding quite differently, with Black women protesting the plan to segregate them.[23] What is clear is that some groups did attempt on the day of the parade to segregate their delegations, and that women like Ida B. Wells-Barnett refused to comply.[24]

Un débat considérable existe au sujet de la séparation des suffragettes de couleur noire dans le défilé. Dans une interview orale d'histoire de 1974, Alice Paul a rappelé "l'obstacle" que Mary Church Terrell a apporté à la délégation de l'Association nationale des femmes de couleur. [25] Les délégations de l'Association Nationale des femmes de couleur et le Chapitre Alpha récemment crée de Delta Sigma Theta Sorority de l'Université d'Howard ont participés et les femmes femmes noires marchèrent dans différents états et dans différents groupes professionnels. Pendant la mémoire de Paul un compromis a été trouvé pour le défilé que les femmes blanches, puis la section des hommes, et enfin la section des femmes nègres, rapportés dans le journal Association Nationale de l'Avancement des Personnes Colorées, ""La Crise"", décrit des événements qui se déroulent tout à fait différemment, avec des femmes noires qui protestent les plans pour les séparer.[26] Il est clair que certains groupes ont tenté le jour de la parade de séparer leurs délégations, et que les femmes telles que Ida B. Wells-Barnett refusée de s'y conformer.[24]

Aftermath[modifier | modifier le code]

Conséquences[modifier | modifier le code]

The mistreatment of the marchers by the crowd and the police caused a great furor. Alice Paul shaped the public response after the parade, portraying the incident as symbolic of systemic government mistreatment of women, stemming from their lack of a voice and political influence through the vote. She claimed the incident showed that the government's role in women's lives had broken down, and that it was incapable of even providing women with physical safety.

Les mauvais traitements infligés aux manifestants par la foule et la police a provoqué une grande fureur . Alice Paul façonné la réaction du public après le défilé , décrivant l'incident comme symbolique de mauvais traitements du gouvernement systémique des femmes , provenant de leur manque d' une voix et une influence politique à travers le vote . Elle a affirmé l'incident a montré que le rôle du gouvernement dans la vie des femmes était tombé en panne , et qu'il était incapable de même offrir aux femmes la sécurité physique .

Journalist Nellie Bly, who had participated in the march, headlined her article "Suffragists are Men's Superiors". Senate hearings, held by a subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, started on March 6, only three days after the march, and lasted until March 17, with the result that the District's superintendent of police was replaced.[27] NAWSA praised the parade and Paul's work on it, saying "the whole movement in the country has been wonderfully furthered by the series of important events which have taken place in Washington, beginning with the great parade the day before the inauguration of the president".[1]

Le journaliste Nellie Bly , qui avait participé à la marche , titrait son article <<suffragettes sont supérieurs d'homme>> . audiences du Sénat , tenue par un sous-comité du [Comité sur le District de Columbia, a commencé le 6 Mars , trois jours seulement après la marche, et a duré jusqu'au 17 Mars, avec le résultat que le surintendant du district de la police a été remplacé. NAWSA loué la parade et le travail de Paul sur elle, en disant: <<l'ensemble du mouvement dans le pays a été merveilleusement favorisé par la série d'événements importants qui ont eu lieu à Washington, en commençant par la grande parade le jour avant l'inauguration du président>>.

Popular culture[modifier | modifier le code]

Culture populaire[modifier | modifier le code]

The procession played a significant role in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels, which chronicled the strategies of Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Woman's Party as they lobbied and protested for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which would assure women's voting rights.[28]

La procession a joué un rôle important dans le film de 2004 Jawed Angels qui chronique les stratégies d'Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, et le Parti de la Femme nationale comme ils ont fait pression et ont protesté pour le passage du 19ème amendement à la Constitution des États-Unis qui assurerait femmes droits de vote.

See also[modifier | modifier le code]

Voir aussi[modifier | modifier le code]

- Sentinelles silencieuses

- Marches de Suffragettes

- 1907 Mud March (U.K.)

- Liste des suffragistes et des suffragettes

- Chronologie du suffrage des femmes

Notes[modifier | modifier le code]

- Sheridan Harvey, « Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 », American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women's History and Culture in the United States, Library of Congress (consulté le )

- Lunardini 1986, p. 20–21

- Lunardini 1986, p. 20–21

- Lunardini 1986, p. 21–22

- Lunardini 1986, p. 23–24

- (en) Ellen D. Baer, Enduring Issues in American Nursing year=2002, New York, Springer Pub. Co. (ISBN 978-0-8261-1632-1, lire en ligne), p. 295

- (en) Crystal Nicole Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching, Harvard University Press, , 217. (ISBN 978-0-674-03562-1, lire en ligne)

- (en) J.D. Zahniser et Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, 137–141 p. (ISBN 978-019-995842-9, lire en ligne)

- Lunardini 1986, p. 21–22

- Lunardini 1986, p. 23–24

- (en) Ellen D. Baer, Enduring Issues in American Nursing year=2002, New York, Springer Pub. Co. (ISBN 978-0-8261-1632-1, lire en ligne), p. 295

- (en) Katherine Adams, Alice Paul and the American Woman Suffrage Campaign, Chicago, University of Illinois, , p. 104

- "Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Estimates for the number of marchers varied, with the Congressional Committee claiming 10,000. Most accounts quoted the 8000 figure; see The New York Times, March 3, 1913, and Lunardini 1986, p. 28

- Woelfle, Gretchen (2009). “TAKING IT to the STREET.” Cobblestone. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- (en) Eleanor Flexner, Century of Struggle, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

- The Washington Post, March 5, 1913; The New York Times, March 4–5, 1913

- (en) Katherine Adams, Alice Paul and the American Woman Suffrage Campaign, Chicago, University of Illinois, , p. 104

- "Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Estimates for the number of marchers varied, with the Congressional Committee claiming 10,000. Most accounts quoted the 8000 figure; see The New York Times, March 3, 1913, and Lunardini 1986, p. 28

- The Washington Post, March 5, 1913; The New York Times, March 4–5, 1913

- Robert A. Gallagher, « I Was Arrested, Of Course », American Heritage, vol. 25, no 2, , p. 20 (lire en ligne)

- « Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 », sur American Women, Library of Congress (consulté le )

- (en) Jill Diane Zahniser et Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power, Oxford University Press, , 144 p. (ISBN 978-0-19-995842-9, lire en ligne)

- Robert A. Gallagher, « I Was Arrested, Of Course », American Heritage, vol. 25, no 2, , p. 20 (lire en ligne)

- « Marching for the Vote: Remember the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 », sur American Women, Library of Congress (consulté le )

- Suffrage Parade: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, Government Printing Office, 1913

- « African American Women and Suffrage », National Women's History Museum (consulté le )

References[modifier | modifier le code]

Références[modifier | modifier le code]

- Harvey, Sheridan. "American Women: Marching for the vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913." American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women’s History and Culture in the United States. January 1, 2001. Accessed April 6, 2015.

- Femme américaine : Une Bibliothèque du Guide du Congrès pour l'étude de l'histoire et de la culture des femmes aux États-Unis. Premier Janvier 2001. Consulté le 6 Avril 2015.

- (en) Christine A. Lunardini, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928, New York, New York University Press, (ISBN 0-8147-5022-2)

- unknown. "Views of Washington, D.C. suffrage parade and crowds. See individual photos for additional description." (1913): ARTstor Digital Library, EBSCOhost (accessed March 26, 2015).

- Inconnu. "Views of Washington, D.C. suffrage parade and crowds. See individual photos for additional description." (1913): ARTstor Bibliothèque numérique EBSCOhost (consulté le 26 Mars 2015).

- Woelfle, Gretchen. "TAKING IT to the STREET." Cobblestone 30, no. 3 (March 2009): 30. MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed March 22, 2015).

- Woelfle, Gretchen. "TAKING IT to the STREET." Pavé 30, no. 3 (Mars 2009): 30. MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost (consulté le 22 Mars 2015).