J. Norman Collie

J. Norman Collie FRSE, FRS | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Norman Collie 10 September 1859 Alderley Edge, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 1 November 1942 (aged 83) Sligachan, Isle of Skye, Scotland |

| Citizenship | British |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society[1] |

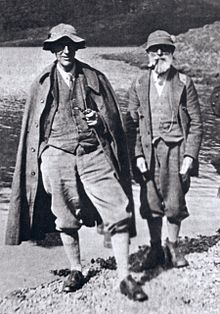

Professor John Norman Collie FRSE FRS[1] (10 September 1859 – 1 November 1942), commonly referred to as J. Norman Collie, was an English scientist, mountaineer and explorer.[2][3][4]

Life and work[edit]

He was born in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, the second of four sons to John Collie and Selina Mary Winkworth.[5] In 1870 the family moved to Clifton, near Bristol, and John was educated initially at Windlesham in Surrey and then in 1873 at Charterhouse School. The family money had been made in the cotton trade, but in 1875 the American Civil War resulted in their financial ruin when their American stock was burnt. Collie had to leave Charterhouse and transfer to Clifton College, Bristol where he realised he was completely unsuited for the classics. He attended University College in Bristol and developed an interest in chemistry.

He earned a PhD in chemistry under Johannes Wislicenus at Würzburg in 1884. Returning to Britain, he taught three years at Cheltenham Ladies College where, according to his niece, "he was far from being a ladies' man and probably found that schoolgirls in bulk were rather more than he could stomach".[6] He left to join University College London (UCL) as an assistant to William Ramsay. His early work was the study of phosphonium and phosphine derivatives and allied ammonium compounds. Later he made important contributions to the knowledge of dehydroacetic acid (then called dehydracetic acid), describing a number of very remarkable 'condensations,' whereby it is converted into pyridine, orcinol and naphthalene derivatives.

Collie served as Professor of Organic Chemistry at UCL from 1896 to 1913, and headed its chemistry department from 1913 to 1928.[7] He performed important research that led to the taking of the first x-ray for diagnosing medical conditions. According to Bentley, Collie "worked with Ramsay on the inert gases, constructed the first neon lamp, proposed a dynamic structure for benzene, and discovered the first oxonium salt."[1] The work on neon discharge lamps was conducted in 1909. The effect of glowing neon in contact with mercury was later sometimes called the Collier effect.[8]

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1888. His proposers included Alexander Crum Brown and Edmund Albert Letts.[5] He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1896.[1][9]

Mountaineering[edit]

Collie's professional career was spent as a scientist but his avocation was mountaineering.[10] Among mountaineers, he is perhaps best remembered for his pioneering climbs on the Cuillin in the Isle of Skye, but he also climbed in the English Lake District and in the Alps with William Cecil Slingsby, Geoffrey Hastings and Albert F. Mummery.

Collie appears to have begun climbing in Skye in 1886. He went there with his brothers to fish but made an ascent of Sgùrr nan Gillean. After two unsuccessful attempts he was given advice on the route by John Mackenzie, a Skye crofter and Britain's first professional mountain guide. Collie returned regularly to Skye and climbed with MacKenzie, the two men becoming firm friends and making many first ascents.

In 1899 he discovered the Cioch, a unique rock feature on the Coire Lagan face of Sron na Ciche. This he climbed in 1906 with Mackenzie, who named it from the Gaelic word for a breast. Collie was instrumental in producing much better maps of the Cuillin which had previously defied the skills of cartographers. He is commemorated in the Cuillin by Sgúrr Thormaid (Norman's Peak; pronounced Skoor Horamitch)[11] He is also remembered in Collie's Ledge, a famously exposed rocky scramble across the west face of Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich, (MacKenzie's Peak) which is named after his great friend.[12] Since the first traverse of this ledge was made by MacKenzie with the Irish climber, Henry Hart, rather than Collie himself, some authoritative publications have begun to use the name Hart's Ledge[13]

In the 1997 BBC TV series on Scottish climbing, The Edge, Collie and MacKenzie's exploits were re-enacted by Alan Kimber (Collie) and John Lyall (MacKenzie).

Collie also made significant ascents on mainland Scotland, notably the first ascent and first winter ascent of Tower Ridge on Ben Nevis with Godfrey Solly and J. Collier on 29 March 1894. The ridge had one previous descent by the Hopkinsons in 1892.[14] In 1894 he also climbed the eponymous Collie's Pinnacle on Bidean nam Bian, Argyll's highest hill, by its short side. (10 metres, grade Easy)[15]

In 1895, Collie, Mummery, and fellow climber Geoffrey Hastings went to the Himalaya Range for the world's first attempt at a Himalayan 8,000-metre peak, Nanga Parbat. They were years ahead of their time, and the mountain claimed the first of its many victims: Mummery and two Gurkhas, Ragobir and Goman Singh were killed by an avalanche and never seen again. The story of this disastrous expedition is told in Collie's book, From the Himalaya to Skye.[16]

After gaining climbing experience on the Alps, the Caucasus and the Himalaya, in 1897 Collie joined the Appalachian Club upon the invitation of Charles Fay, and spent the summer climbing in the Canadian Rockies. From 1898 to 1911, Collie visited the Canadian Rockies five more times, accomplishing twenty-one first ascents and naming more than thirty peaks. He was particularly interested in locating and climbing the mythical giants of Hooker and Brown which had bordered the forgotten fur trade route through the Rockies and were reputed to be over 16,000 feet high. In 1903, Collie and Hugh Stutfield published an authoritative book on the region, Climbs and Explorations in the Canadian Rockies.

Death[edit]

Collie retired in 1929 and thereafter spent his summers in Skye. He died at Sligachan in November 1942 from pneumonia, after falling into Loch Leathan below the Storr a year earlier whilst fishing. In keeping with his wishes, he was interred next to his friend, John MacKenzie, in an old graveyard at Struan by Bracadale next to Loch Harport.[17]

Influence[edit]

In a book published in 2013 it is suggested that Collie may have inspired Conan Doyle with some characteristics for Sherlock Holmes. Apart from his mountaineering skills Collie was a confirmed bachelor sharing his house with a solicitor. With an analytical mind honed by chemical research he had wide interests ranging from Chinese porcelain to fishing and from claret to horse racing. In addition he was an incessant pipe smoker only lighting a cigarette when refilling his pipe.[18]

Honours and affiliations[edit]

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1896)[1]

- Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (1897)

- President of the Alpine Club (1920–22)

- Member of the Mount Everest Committee (1921)

- Mount Collie in Yoho National Park and Sgurr Thormaid (Norman's Peak) on the Isle of Skye were both named after Norman Collie.

Memorial[edit]

A ten-year project raised funding to erect a bronze statue and memorial to John MacKenzie and Norman Collie on Skye.[19] The bronze was designed by local sculptor, Stephen Tinney. It was unveiled on a rocky knoll opposite the Sligachan Hotel, overlooking the Cuillin Hills, in September 2020.[20][21]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Baly, E. C. C. (1943). "John Norman Collie. 1859–1942". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 4 (12): 329–356. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1943.0007. S2CID 191496493.

- ^ Bentley, R. (1999). "John Norman Collie: Chemist and Mountaineer". Journal of Chemical Education. 76 (1): 41. Bibcode:1999JChEd..76...41B. doi:10.1021/ed076p41.

- ^ Mill, Christine (1987). Norman Collie, a life in two worlds: mountain explorer and scientist, 1859–1942. [Aberdeen]: Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-08-032456-8.

- ^ Taylor, William J. (1973). The snows of yesteryear: J. Norman Collie, mountaineer. Toronto: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada. ISBN 0-03-929953-8.

- ^ a b "Dr Norman Macleod FRSE". www.rse.org.uk. Royal Society of Edinburgh. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Simon (2010). Unjustifiable risk? : The Story of British climbing. Milnthorpe: Cicerone. p. 71. ISBN 9781852846275. quoting Mill, Christine (1987). Norman Collie : a life in two worlds : mountain explorer and scientist 1859-1942. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0080324562.

- ^ See the UCL Department of Chemistry page on Collie

- ^ Collie, J. Norman (1909). "Note on a Curious Property of Neon". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. 82 (555): 378–380. Bibcode:1909RSPSA..82..378C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1909.0041. JSTOR 92952.

- ^ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 23 December 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Collie, Norman (2007). Climbing on the Himalaya and other Mountain Ranges. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-548-22421-2.

- ^ Ken Crocket, Mountaineering in Scotland : The Early Years,(Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 2015) pp40-46

- ^ S.P. Bull, Black Cuillin Ridge ; Scramblers' Guide, (Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust,1993),77.

- ^ Noel Williams,Skye Scrambles,(Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust,2017),250

- ^ J.R. Marshall, Climbers' guide to Ben Nevis (Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust,1969)94

- ^ L.S. Lovat,Climbers Guide to Glencoe and Ardgour, Vol. 2(Edinburgh: W&R Chambers for The Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 1965)p9

- ^ Collie, Norman (2003). From the Himalaya to Skye. Rockbuy Limited. ISBN 1-904466-08-7.

- ^ Ken Crocket, Mountaineering in Scotland : The Early Years,(Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 2015) 53

- ^ Davies & Garrett, A.G. & P.J. (2013). UCL Chemistry Department 1828–1974. Science Reviews 2000 Ltd. ISBN 978-1-900814-46-1.

- ^ Brian Ferguson (23 July 2016). "Skye to honour legendary Scots climbers with work of art". The Scotsman.

- ^ "Collie and MacKenzie Heritage Group". Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "The friends who revealed wonders of Skye's Black Cuillin". BBC. 26 September 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Mummery, A. F. (1895). My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

climbs mummery.

- Collie, Norman (1902). Climbing on the Himalaya and other Mountain Ranges. D. Douglas.

External links[edit]

- 1859 births

- 1942 deaths

- People from Alderley Edge

- English chemists

- British organic chemists

- British mountain climbers

- Explorers of British Columbia

- Presidents of the Alpine Club (UK)

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society

- Academics of University College London

- People educated at Charterhouse School

- Sportspeople from Cheshire