Italian ironclad San Martino

Illustration of San Martino, c. 1886

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | San Martino |

| Namesake | Martin of Tours |

| Builder | FCM |

| Laid down | 22 July 1862 |

| Launched | 21 September 1863 |

| Completed | 9 November 1864 |

| Stricken | 1903 |

| Fate | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Regina Maria Pia-class ironclad warship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 81.2 m (266 ft 5 in) |

| Beam | 15.24 m (50 ft) |

| Draft | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12.6 knots (23.3 km/h; 14.5 mph) |

| Range | 2,600 nmi (4,800 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 480–485 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

San Martino was a Regina Maria Pia-class ironclad warship, the second member of her class. She was built for the Italian Regia Marina in the 1860s; like her three sister ships, she was built in France. San Martino was laid down in July 1862, was launched in September 1863, and was completed in November 1864. The ships were broadside ironclads, mounting a battery of four 203 mm (8 in) and twenty-two 164 mm (6.5 in) guns on the broadside.

San Martino saw action at the Battle of Lissa, fought during the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866. There she was in the center of the action, at the head of the Italian main body. Of the three ships in her division, San Martino was the only vessel to survive the battle. After the war, the ship's career was uneventful, the result of the emergence of more modern ironclads and a severe reduction in the Italian naval budget following their defeat at Lissa. She was rebuilt as a central battery ship some time after Lissa, and was modernized again in the late 1880s. The ship was eventually broken up for scrap in 1903.

Design[edit]

San Martino was 81.2 meters (266 ft) long overall; she had a beam of 15.24 m (50 ft) and an average draft of 6.35 m (20.8 ft). She displaced 4,201 long tons (4,268 t) normally and up to 4,527 long tons (4,600 t) at full load. The ship had an inverted bow with a pronounced ram below the waterline. She had a crew of 480–485 officers and men.[1]

Her propulsion system consisted of one single-expansion steam engine that drove a single screw propeller. Steam was supplied by eight coal-burning, rectangular fire-tube boilers that were vented through a single funnel. Her engine produced a top speed of 12.6 knots (23.3 km/h; 14.5 mph) from 2,620 indicated horsepower (1,950 kW). She could steam for 2,600 nautical miles (4,800 km; 3,000 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). The ship was initially schooner-rigged to supplement the steam engine, though her masts were later reduced to a barque rig. Ultimately, she lost her sailing rig completely, having it replaced with a pair of military masts with fighting tops.[1]

She was a broadside ironclad, and she was initially armed with a main battery of four 203 mm (8 in) guns and twenty-two 164 mm (6.5 in) guns, though her armament changed throughout her career. The ship was protected by iron belt armor that was 121 mm (4.75 in) thick and extended for the entire length of the hull at the waterline. The battery deck was protected by 110 mm (4.3 in) of iron plate.[1]

Service history[edit]

The keel for San Martino was laid down at the Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée shipyard in La Seyne, France, on 22 July 1862. She was launched on 21 September 1863, and completed on 9 November 1864.[1] In June 1866, Italy declared war on Austria, as part of the Third Italian War of Independence, which was fought concurrently with the Austro-Prussian War.[2] The Italian fleet commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, initially adopted a cautious course of action; he was unwilling to risk battle with the Austrian Navy, despite the fact that the Austrian fleet was much weaker than his own. Persano claimed he was simply waiting on the ironclad ram Affondatore, en route from Britain, but his inaction weakened morale in the fleet, with many of his subordinates openly accusing him of cowardice.[3]

Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff brought the Austrian fleet to Ancona on 27 June in an attempt to draw out the Italians. At the time, many of the Italian ships were in disarray; several ships did not have their entire armament, and several others had problems with their engines. San Martino was one of the few ironclads fit for action, so she, Castelfidardo, Regina Maria Pia, and Principe di Carignano formed up to prepare to attack Tegetthoff's ships. Persano held a council of war aboard Principe di Carignano to determine whether he should sortie to engage Tegetthoff, but by that time, the Austrians had withdrawn, making the decision moot. The Minister of the Navy, Agostino Depretis, urged Persano to act and suggested the island of Lissa, to restore Italian confidence after their defeat at the Battle of Custoza the previous month. On 7 July, Persano left Ancona and conducted a sweep into the Adriatic, but encountered no Austrian ships and returned on the 13th.[4]

Battle of Lissa[edit]

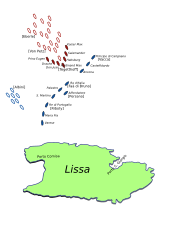

On 16 July, Persano took the Italian fleet out of Ancona, bound for Lissa, where they arrived on the 18th. With them, they brought troop transports carrying 3,000 soldiers; the Italian warships began bombarding the Austrian forts on the island, with the intention of landing the soldiers once the fortresses had been silenced. In response, the Austrian Navy sent the fleet under Tegetthoff to attack the Italian ships.[5] At that time, San Martino was assigned to the 2nd Division, under Persano, along with the ironclad Re d'Italia and the coastal defense ship Palestro.[6] After arriving off Lissa on the 18th,[2] Persano sent most of his ships to bombard the town of Vis, but Persano was unable to effect the landing. The next morning, Persano ordered another attack; four ironclads would force the harbor defenses at Vis while San Martino and the rest of the fleet would attempt to suppress the outer fortifications. This second attack also proved to be a failure, but Persano decided to make a third attempt the next day. San Martino and the bulk of the fleet would again try to disable the outer forts in preparation for the landing.[7]

Before the Italians could begin the attack, the dispatch boat Esploratore arrived, bringing news of Tegetthoff's approach. Persano's fleet was in disarray; the three ships of Admiral Giovanni Vacca's 1st Division were three miles to the northeast from Persano's main force, and three other ironclads were further away to the west. Persano immediately ordered his ships to form up with Vacca's, first in line abreast formation, and then in line ahead formation. San Martino was at the center of the Italian line. Shortly before the action began, Persano decided to leave his flagship and transfer to Affondatore, though none of his subordinates on the other ships were aware of the change. They there thus left to fight as individuals without direction. More dangerously, by stopping Re d'Italia, he allowed a significant gap to open up between Vacca's three ships and the rest of the fleet.[8]

Tegetthoff took his fleet through the gap between Vacca's and Persano's ships, though he failed to ram any Italian vessels on the first pass. The Austrians then turned back toward Persano's ships, and took Re d'Italia, San Martino, and Palestro under heavy fire. San Martino initially engaged the unarmored ships of the Austrian 2nd Division, but as Re d'Italia became embroiled in the ensuing melee, San Martino's captain attempted to come to her aid, though the ship was unable to prevent the Austrian flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max, from ramming and sinking her. Tegetthoff immediately ordered his crew to lower boats to pick up the men in the water, but with San Martino fast approaching, he could not leave his ship a stationary target. He instead ordered the small aviso Kaiserin Elizabeth to pick up the Italian survivors, but she too came under fire and was forced to abandon the effort.[9]

During the battle, San Martino collided with Regina Maria Pia and had her ram bow twisted, causing leaks in her hull. Shortly thereafter, Persano broke off the engagement to consolidate his forces, but his ships, low on coal and ammunition, and with badly demoralized crews, could not be rallied by Persano's half-hearted attempt to launch an attack. The Italian fleet began to withdraw, followed by the Austrians; as night began to fall, the opposing fleets disengaged completely, heading for Ancona and Pola, respectively. San Martino had been hit numerous times, and had her side armor penetrated by one shell, which did not succeed in penetrating the timber backing. Twice during the engagement, the ship was set on fire by Austrian shells, though her crew was able to put the fires out. After the battle, Vacca replaced Persano; he was ordered to attack the main Austrian naval base at Pola, but the war ended before the operation could be carried out.[10]

Later career[edit]

For the rest of her long career, San Martino served in a variety of roles, both in the main fleet and in Italy's colonial empire.[11] After the war, the Italian government slashed the naval budget so significantly that the fleet had great difficulty in mobilizing its ironclad squadron to attack the port of Civitavecchia in September 1870, as part of the wars of Italian unification. Instead, the ships were laid up and the sailors conscripted to man them were sent home.[12] Some time after 1866, the ship was rebuilt as a central battery ship, with most of her guns located in a central, armored casemate. Two other guns were placed in the bow as chase guns, with a third mounted as a stern chaser. At this time, her armament was also revised, to two 220 mm (8.7 in) guns in the bow and nine 8 in guns, four on each broadside and the last in the stern.[1] By October 1871, the ship was stationed in La Spezia, along with her sisters Regina Maria Pia and Castelfidardo, Affondatore, and the new ironclad Roma.[13] In August 1873, San Martino, Roma and the paddle steamer Plebiscito visited Barcelona, Spain. where they met a number of other foreign warships, including the French ironclad Jeanne d'Arc, the British ironclad HMS Pallas and corvette Rapid, and the United States frigate USS Wabash. San Martino had moved to Valencia in September.[14]

On 10 June 1887, the annual fleet maneuvers began; San Martino was assigned to the "attacking squadron", along with the ironclads Ancona and Duilio, the protected cruiser Giovanni Bausan, and several smaller vessels. The first half of the maneuvers tested the ability to attack and defend the Strait of Messina, and concluded in time for a fleet review by King Umberto I on the 21st.[15] San Martino took part in the annual 1888 fleet maneuvers, along with the ironclads Lepanto, Italia, Duilio, and Enrico Dandolo, one protected cruiser, four torpedo cruisers, and numerous smaller vessels. The maneuvers consisted of close-order drills and a simulated attack on and defense of La Spezia.[16] Between 1888 and 1890, the ship had her barque rig replaced with military masts. By this time, she had been rearmed with eight 152 mm (6 in) guns in the casemate and several smaller guns for close-range defense against torpedo boats. These included five 120 mm (4.7 in) guns, four 57 mm (2.2 in) guns, and eight 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannons. She also received three torpedo tubes.[1] In 1894, the ship was assigned to the Third Division of the Italian fleet, along with the newly commissioned protected cruiser Liguria and the torpedo cruiser Confienza.[17] Beginning on 14 October that year, the Italian fleet, including San Martino, assembled in Genoa for a naval review held in honor of King Umberto I at the commissioning of the new ironclad Re Umberto. The festivities lasted three days.[18] The next year, she was stationed in La Spezia.[19] The ship was stricken from the naval register in 1903 and thereafter broken up for scrap.[1]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Fraccaroli, p. 339.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, p. 1.

- ^ Greene & Massignani, pp. 217–222.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Wilson, p. 219.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 220–224.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 223–225, 232–233.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 234–238, 247.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 238–245, 250–251.

- ^ Ordovini, Petronio, & Sullivan, pp. 343–343.

- ^ Fraccaroli, p. 336.

- ^ Dupont, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Bewegungen, pp. 16, 18.

- ^ Beehler, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Brassey, p. 453.

- ^ Garbett May 1894, p. 565.

- ^ Garbett November 1894, p. 1295.

- ^ Garbett 1895, p. 89.

References[edit]

- Beehler, W. H. (1887). "Naval Manoevres, 1887: Italian". Information from Abroad. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office: 164–167. OCLC 12922775.

- "Bewegungen S. M. Kriegsschiffe vom 1. September 1873 bis 31. August 1874" [Movements of S. M. Warships from 1 September 1873 to 31 August 1874]. Jahrbuch der Kais. Kön. Kriegsmarine [Yearbook of the Imperial and Royal Navy]. Pola: Verlag der Redaction: 15–26. 1874.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1889). "Foreign Naval Manoevres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 450–455. OCLC 5973345.

- Dupont, Paul, ed. (1872). "Notes sur La Marine Et Les Ports Militaires de L'Italie" [Notes on the Navy and Military Ports of Italy]. La Revue Maritime et Coloniale [The Naval and Colonial Review] (in French). XXXII. Paris: Imprimerie Administrative de Paul Dupont: 415–430.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1979). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 334–359. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1894). "Naval and Military Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXVIII. London: Harrison & Sons: 557–572.

- Garbett, H., ed. (November 1894). "Naval and Military Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXVIII (201). London: J. J. Keliher: 193–206. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1895). "Naval and Military Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXIX (203). London: J. J. Keliher & Co.: 81–110. OCLC 8007941.

- Greene, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-938289-58-6.

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio & Sullivan, David M. (December 2014). "Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part I: The Formidabile, Principe di Carignano, Re d'Italia, Regina Maria Pia, Affondatore, Roma and Principe Amedeo Classes". Warship International. Vol. 51, no. 4. pp. 323–360. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.

External links[edit]

- San Martino Marina Militare website (in Italian)