Francesco Nullo

Francesco Nullo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 March 1826 |

| Died | 5 May 1863 (aged 37) |

| Movement | Il Risorgimento (Unification of Italy) |

Francesco Nullo (1 March 1826 – 5 May 1863) was an Italian patriot, military officer and merchant, and a close friend and confidant of Giuseppe Garibaldi. He supported independence movements in Italy and Poland. He was a participant in the Five Days of Milan and other events of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states, Sicilian Expedition of the Thousand in 1860 and the Polish January Uprising in 1863. His military career ended with him receiving the rank of general in Poland, shortly before his death in the Battle of Krzykawka.

Youth[edit]

Francesco Nullo was born on 1 March 1826 in Bergamo, as a son of Arcangelo and Angelina Magno, a wealthy family of linen traders.[1][2] He had five younger brothers.[1] He finished primary school there, with distinction, and continued his education in the Collegio Celana in Val San Martino (Caprino Bergamasco); a former ecclesiastic seminary, one of the best boarding schools in the region.[1][2] In 1840 he returned to work in his family's textile factory, but left soon afterward to study in Milan; there he became involved in the revolutionary movement for Italian unification.[1][2]

Struggle for Italian independence[edit]

During the revolutions of 1848, along with his two brothers he took part in fighting during the Five Days of Milan.[1][2] In 1849 he fought near Rome, and retreated together with Giuseppe Garibaldi to San Marino.[1] In 1850 he returned to Bergamo, where he resumed his life as a textile merchant for the next decade.[1]

In 1859, motivated by the resurgence of Italian patriotism, he joined Garibaldi in the ranks of Hunters of the Alps to fight against the Austrians. On 3 May in Turin he formed a unit of volunteers.[1] On 27 May he took part in the Battle of San Fermo.[1] Nullo became widely known for the Sicilian Expedition of the Thousand, where he commanded the Iron Company (or Iron Brigade).[2][3] He personally supervised the enrollment of volunteers in Bergamo which, given the large number of accessions (more than 10% of the total), could then boast the title of City of the Thousand. Due to his previous experience in the textile industry, he provided the red shirts used by Italian "garibaldini" (voluntary troops at Garibaldi's command), who became known as the "red shirts". He was wounded in the Battle of Calatafimi, but just a few days later led his soldiers in a charge at the Battle of Palermo.[1][2] He was the one who planted the first Italian flag in Palermo on 27 May 1860. He fought in the victorious Battle of Reggio in Calabria, and was promoted to major soon afterward.[1]

He wrote in the Book of Honor of Bergamo's volunteers:

I am proud to belong to the ranks of the valiant sons of Bergamo who adorn the pages of this book of honor and to see my name alongside those of many brothers in arms

— Bortolo Belotti, Storia di Bergamo e dei bergamaschi, Bergamo, Bolis, 1989

In 1862 Nullo was arrested along with 123 other partisans while organizing an expedition for the liberation of Austrian-ruled Veneto (considered too dangerous by the newly established Kingdom of Italy). He was soon released, under the pressure of numerous demonstrators calling to "Release Nullo".[2]

He continued to be a faithful companion to Garibaldi in the second expedition to Sicily, including at the Battle of Aspromonte (1862), when the Italian Army had to stop Garibaldi in his attempt to reach and conquer Rome, which was protected by France. Garibaldi was injured in the battle, and Nullo was responsible for saving him.[1]

In the 1863 Polish January Uprising[edit]

After the overthrow of the government of Urbano Rattazzi, because of the popular indignation at the events in Aspromonte, the new prime minister Luigi Carlo Farini encouraged Nullo to form a legion of volunteers to intervene on the side of Polish insurgents against Russian domination, ensuring his lobbying at King Vittorio Emanuele II, to declare war on the Russian Empire. Nullo, already friends with Poles such as Ludwik Mierosławski and Marian Langiewicz, who supported him and Garibaldi in their past fights, quickly took to the Polish cause, soon organizing meetings in Bergamo and recruiting volunteers for the Polish cause, recalling Polish support for the Italian cause during the Napoleonic wars (Polish Legions in Italy), and even more so, during the Spring of Nations (Mickiewicz's Legion).[1][2]

Farini was considered insane and forced to resign, but Nullo could leave for Poland, gathering some Italian volunteers (sources vary with regards to their number, but most reliable ones settle on about twenty).[4] The group, commanded by Nullo, became known as the Garibaldi Legion.[3][5] During the trip, the Italian group was joined by a small groups of Polish emigres and the French volunteer unit, the Zouaves of Death, led by Lieutenant François Rochebrune. The Italians and the French were sometimes referred to as the Foreign Legion.[3]

Nullo with a selected cadre of a dozen or so volunteers reached Kraków in April 1863.[1] They were incorporated into the unit of colonel Józef Miniewski.[1][2] The Legion crossed the borders of Congress Poland on the night of 3–4 May near Ostrężnica and Czyżówka, after organizing in Krzeszowice.[1] Early in the morning of the 4th the unit's first battle in Poland occurred at Podłęże where it defeated a Russian force (the garrison from Olkusz).[1][2] The Polish National Government awarded him the rank of general.[3][5] With a Polish unit commanded by colonel Miniewski he marched on Olkusz.[3] On the morning of 5 May they reached Krzykawka.[1]

Subsequently, on 5 May, the Legion, along with the Polish unit under Miniewski, took part in the Battle of Krzykawka. In the first stage of the battle, the insurgents push the Russian troops back in close fighting; but subsequent Russian reinforcements turned the tide and the insurgents and their foreign allies suffered heavy casualties; both Miniewski and Nullo were killed in that battle.[5] Nullo was mortally injured leading the charge.[1] Hit by a Cossack bullet while preparing (or leading) a charge (sources vary), he had only time to whisper, in Bergamo dialect: So' mort! (I'm dead).[1][2] Several other Italians were killed in this battle, and some were taken prisoner and deported to Siberia, including the cornigliese Giovanni Rustici.[6]

Remembrance[edit]

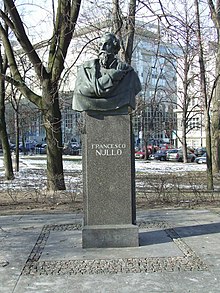

In Italy, one of the Sauro class destroyers was named after him.[7] The warship was built at Fiume naval shipyards and took service between 1927 and 1940. In Bergamo, his hometown, he was dedicated a statue, erected in 1907 by sculptor Ernesto Bazzaro nearby the main city theatre. In 1937 an urn with soil from his tomb was offered by Polish legioners to the Bergamo Municipality. It is preserved in the town's Museum of Risorgimento.[8][9] Several schools in Poland are named after him.[10][11]

In Poland Nullo is considered a national hero. On 8 May he was buried in the cemetery in Olkusz, together with several other soldiers killed in the battle of Krzykawka, and on 12 May a mass in his name was held in Kraków.[2][12] Even before Poland regained its independence, a monument dedicated to him was built there by the local community; it was raised illegally as at that time Olkusz was still part of the Russian partition.[2][12] In 1915 a memorial to Nullo and other soldiers was raised on the battle site near Krzykawka; the field is known as Nullo's Field.[13] In the Second Polish Republic, in 1923, on the 60th anniversary of the battle, a ceremony was held there, attended by government officials and with the writer Stefan Żeromski giving a eulogy.[12] In 1931 a Polish-Italian ceremony was held at the graveyard.[12] He was the patron of the 50 Regiment of Kresy Riflemen (50 Pułk Piechoty Strzelców Kresowych).[14] Even during the Cold War years, a consul went to Bergamo to pay him homage at the foot of the monument dedicated to him in his hometown. In 1963, on the battle's 100th anniversary, an Italian delegation visited the cemetery, adding another plaque and several trees.[12] Nine streets and three schools in Poland bear his name. He is also commemorated in several poems.[15] There is also a monument in Warsaw (on a street bearing his name), the monument was unveiled on 26 February 1939 by Galeazzo Ciano.[16] On the 130th anniversary of his death, 5 May 1993, Polish Post issued a stamp dedicated to him.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t (in Polish) Sylwetka Patrona Archived 2018-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m (in Polish) Patron Szkoły

- ^ a b c d e (in Polish) NULLO Francesco (1826-63)

- ^ Monica Gardner, An Italian Tragedy in Siberia, The Sewanee Review, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1926), pp. 329-338

- ^ a b c (in Polish) WIEM Encyklopedia, Nullo Francesco

- ^ Parma e la sua storia Archived 2015-11-20 at the Wayback Machine - Giovanni Rustici (Parma Municipal Library System)

- ^ Chris Marshall (1995). The encyclopedia of ships: the history and specifications of over 1200 ships. Barnes & Noble. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-56619-909-4. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Comune di Bergamo[permanent dead link] - statue of Nullo

- ^ Statue of Nullo in Bergamo

- ^ "Szko³a Podstawowa Numer 100 im. Francesco Nullo". sp100.edu.pl.

- ^ "Szko艂a Podstawowa nr 4 im. Francesco Nullo w Olkuszu". ilkus.pl.

- ^ a b c d e Olkusz 1. TABLICE PAMIĘCI NARODOWEJ 2. Pomnik Francesco Nullo na starym cmentarzu w Olkuszu

- ^ (in Polish) Polana Nullo

- ^ Koreś D., 50 Pułk Piechoty Strzelców Kresowych im. Francesco Nullo, AJAKS, 2007, ISBN 978-83-88773-79-2

- ^ (in Polish) Pułkownik Nullo w pieśni i w poezji

- ^ (in Polish) Ulica gen. Francesco Nullo

- ^ "Filatelistyka, filatelista, znaczki pocztowe, katalog znaczkw pocztowych, encyklopedia filatelistyki". filatelistyka.org.

Sources[edit]

- Italian

- Studi del Museo Storico di Bergamo.

- Atti, Storia del Risorgimento nazionale, documenti ed oggetti presentati dalla commissione nominata dal municipio di Bergamo, Bolis, Bergamo 1884, SBN IEI0228043;

- Giuliana Donati Petténi, La biografia di Francesco Nullo, Bergamo 1960;

- Giuliana Donati Petténi, La spedizione di Francesco Nullo in Polonia, in AA.VV., Storia del volontarismo bergamasco, a cura di Alberto Agazzi, Istituto Civitas Garibaldina, Società Editrice S. Alessandro, Bergamo 1960;

- Giuliana Donati Petténi, Francesco Nullo, cavaliere della libertà, Bolis, Bergamo 1963;

- Vittorio Polli, Francesco Nullo, Istituto Civitas Garibaldina, Stamperia Conti, Bergamo 1964;

- Bortolo Belotti, Storia di Bergamo e dei bergamaschi, Bolis, Bergamo 1989;

- Alberto Castoldi, Bergamo e il suo territorio, dizionario enciclopedico: i personaggi, i comuni, la storia, l'ambiente, Bolis, Bergamo 2004, ISBN 88-7827-126-8;

- Renato Ravanelli, La storia di Bergamo, Grafica & Arte, Bergamo 1996, ISBN 88-7201-133-7.

- Polish

- Adam Ostrowski, Francesco Nullo, bohater Polski i Włoch, Nasza Księgarnia, 1970

External links[edit]

Media related to Francesco Nullo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Francesco Nullo at Wikimedia Commons Polish Wikisource has original text related to this article: "Ku czci Franciszka Nullo", Stefan Żeromski (1923)

Polish Wikisource has original text related to this article: "Ku czci Franciszka Nullo", Stefan Żeromski (1923)

- 1826 births

- 1863 deaths

- 19th-century Italian businesspeople

- Italian military personnel

- Italian people of the Italian unification

- Italian revolutionaries

- Polish military personnel

- Businesspeople from Bergamo

- People of the Revolutions of 1848

- January Uprising participants

- Italy–Poland relations

- Italian emigrants to Poland