Utilisateur:Immunoman/Atelier

L'immunité est un terme médical qui désigne l'état d'un organisme vivant qui possède des défenses biologiques suffisantes pour éviter les infections, les maladies et toute infestation par d'autre organismes. L'immunité implique tous les acteurs du systèmes immunitaires, spécifiques de l'antigène ou non.

Vue d'ensemble[modifier | modifier le code]

Les acteurs non spécifiques agissent comme barrière ou éliminent les pathogènes pour enrayer les invasions par des micro-organismes avant qu'ils ne provoquent de maladies. Certains cellules de l'immunité innée participent à l'élaboration d'une immunité spécifique de l'antigène.

L'immunité spécifique ou adaptative, impliquant des lymphocytes T et B est diviséee en deux catégories selon la manière dont l'immunité a été formée. L'immunité naturelle se met en place lorsqu'un organisme a créé de lui-même une défense contre un agent pathogène introduit sans dessein; l'immunité artificielle se développe uniquement dans des situations d'immunisation délibérée. Une autre division peut être faite selon que les agents de l'immunité de l'organisme sont endogènes ou exogènes.

Types de réponse immunitaire[modifier | modifier le code]

Immunité passive[modifier | modifier le code]

L'immunité passive est constituée par le transfert d'éléments de l'immunité d'un organisme dans un autre. Ces éléments peuvent être des cellules ou des anticorps, issu d'un individu immunisé vers un autre non-immunisé. L'immunité passive existe naturellement dans les relations materno-foetales

Passive immunity is the transfer of active immunity, in the form of readymade antibodies, from one individual to another. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and can also be induced artificially, when high levels of human (or horse) antibodies specific for a pathogen or toxin are transferred to non-immune individuals. Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response, or to reduce the symptoms of ongoing or immunosuppressive diseases.[1] Passive immunity provides immediate protection, but the body does not develop memory, therefore the patient is at risk of being infected by the same pathogen later.[2]

Naturally acquired passive immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

Maternal passive immunity is a type of naturally acquired passive immunity, and refers to antibody-mediated immunity conveyed to a fetus by its mother during pregnancy. Maternal antibodies (MatAb) are passed through the placenta to the fetus by an FcRn receptor on placental cells. This occurs around the third month of gestation.[3] IgG is the only antibody isotype that can pass through the placenta.[3] Passive immunity is also provided through the transfer of IgA antibodies found in breast milk that are transferred to the gut of the infant, protecting against bacterial infections, until the newborn can synthesize its own antibodies.[2]

Artificially acquired passive immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

see also: Temporarily-induced immunity

Artificially acquired passive immunity is a short-term immunization induced by the transfer of antibodies, which can be administered in several forms; as human or animal plasma or serum, as pooled human immunoglobulin for intravenous (IVIG) or intramuscular (IG) use, and in the form of monoclonal antibodies (MAb). Passive transfer is used prophylactically in the case of immunodeficiency diseases, such as hypogammaglobulinemia.[4] It is also used in the treatment of several types of acute infection, and to treat poisoning.[1] Immunity derived from passive immunization lasts for only a short period of time, and there is also a potential risk for hypersensitivity reactions, and serum sickness, especially from gamma globulin of non-human origin.[2]

The artificial induction of passive immunity has been used for over a century to treat infectious disease, and prior to the advent of antibiotics, was often the only specific treatment for certain infections. Immunoglobulin therapy continued to be a first line therapy in the treatment of severe respiratory diseases until the 1930’s, even after sulfonamide antibiotics were introduced.[4]

Passive transfer of cell-mediated immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

Passive or "adoptive transfer" of cell-mediated immunity, is conferred by the transfer of "sensitized" or activated T-cells from one individual into another. It is rarely used in humans because it requires histocompatible (matched) donors, which are often difficult to find. In unmatched donors this type of transfer carries severe risks of graft versus host disease.[1] It has, however, been used to treat certain diseases including some types of cancer and immunodeficiency. This type of transfer differs from a bone marrow transplant, in which (undifferentiated) hematopoietic stem cells are transferred.

Active Immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

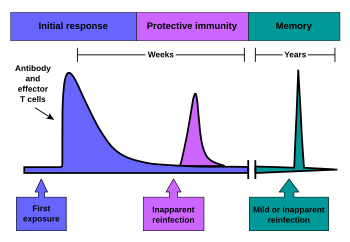

When B cells and T cells are activated by a pathogen, memory B-cells and T- cells develop. Throughout the lifetime of an animal these memory cells will “remember” each specific pathogen encountered, and are able to mount a strong response if the pathogen is detected again. This type of immunity is both active and adaptive because the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges. Active immunity often involves both the cell-mediated and humoral aspects of immunity as well as input from the innate immune system. The innate system is present from birth and protects an individual from pathogens regardless of experiences, whereas adaptive immunity arises only after an infection or immunization and hence is "acquired" during life.

Naturally acquired active immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

Naturally acquired active immunity occurs when a person is exposed to a live pathogen, and develops a primary immune response, which leads to immunological memory.[1] This type of immunity is “natural” because it is not induced by man. Many disorders of immune system function can affect the formation of active immunity such as immunodeficiency (both acquired and congenital forms) and immunosuppression.

Artificially acquired active immunity[modifier | modifier le code]

Erreur : La version française équivalente de {{Main}} est {{Article détaillé}}.

Artificially acquired active immunity can be induced by a vaccine, a substance that contains antigen. A vaccine stimulates a primary response against the antigen without causing symptoms of the disease.[1]The term vaccination was coined by Edward Jenner and adapted by Louis Pasteur for his pioneering work in vaccination. The method Pasteur used entailed treating the infectious agents for those diseases so they lost the ability to cause serious disease. Pasteur adopted the name vaccine as a generic term in honor of Jenner's discovery, which Pasteur's work built upon.

In 1807, the Bavarians became the first group to require that their military recruits be vaccinated against smallpox, as the spread of smallpox was linked to combat.[5] Subsequently the practice of vaccination would increase with the spread of war.

There are four types of traditional vaccines:[6]

- Inactivated vaccines are composed of micro-organisms that have been killed with chemicals and/or heat and are no longer infectious. Examples are vaccines against flu, cholera, bubonic plague, and hepatitis A. Most vaccines of this type are likely to require booster shots.

- Live, attenuated vaccines are composed of micro-organisms that have been cultivated under conditions which disable their ability to induce disease. These responses are more durable and do not generally require booster shots. Examples include yellow fever, measles, rubella, and mumps.

- Toxoids are inactivated toxic compounds from micro-organisms in cases where these (rather than the micro-organism itself) cause illness, used prior to an encounter with the toxiod. Examples of toxoid-based vaccines include tetanus and diphtheria.

- Subunit -vaccines are composed of small fragments of disease causing organisms. A characteristic example is the subunit vaccine against Hepatitis B virus.

Most vaccines are given by hypodermic injection as they are not absorbed reliably through the gut. Live attenuated Polio and some Typhoid and Cholera vaccines are given orally in order to produce immunity based in the bowel.

See also[modifier | modifier le code]

References[modifier | modifier le code]

- Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook: USC School of Medicine

- (en) Charles Janeway, Paul Travers, Mark Walport, and Mark Shlomchik, Immunobiology; Fifth Edition, New York and London, Garland Science, (lire en ligne).

- Coico, R., Sunshine, G., and Benjamin, E. (2003). “Immunology: A Short Course.” Pg. 48.

- Keller, Margaret A. and E. Richard Stiehm, « Passive Immunity in Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases. », Clinical Microbiology Reviews, vol. 13, no 4, , p. 602-614 (lire en ligne)

- National Institutes of Health "Smallpox - A Great and Terrible Scourge" Variolation

- Immunization: You call the shots. The National Immunization Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Modèle:Immune system [[Catégorie:Immune system]] [[Catégorie:Immunology]]